When the word “redelineation” is raised among Malaysians, it is full of negative connotations that also include other ideas like gerrymandering and “bias towards Barisan Nasional”. When The Economist explained the manipulations used for this 14th general elections’ (GE14) electoral boundaries, the Election Commission chief slammed the weekly’s report as “slanderous and causing anxiety” among the Malaysian voters. So why should a typical and regular maintenance of the electoral system such as redelineation be so controversial?

Redelineation is the process of apportioning and districting voters. Apportionment means allocation of constitutencies within an administrative unit like a state or country. Districting, on other hand, determines how boundaries would be drawn to ensure apportionment is done according to the constitution. Redelineation of electoral boundaries ought to be done when there are changes to population distribution and growth of the nation and its states. It’s a necessity and not “evil” when not manipulated, ensuring a fair representation of voters, irrespective of background and geography.

In Malaysia’s first-past-the-post system of voting, the popular vote doesn’t count or significantly influence the formation of a new government. It’s an electoral system vulnerable to manipulations that can be made worse by redelineation. Malaysia’s federal constitution has laid guiding principles for the redelineation under the 13th Schedule. Since Merdeka in 1957, the redelineation process under the constitution has been regularly modified to allow rampant manipulation of electoral boundaries—it has resulted in malapportionment and gerrymandering.

Malapportionment is the creation of electoral districts with divergent ratios of voters to representatives. It is poor and unfair apportionment of voters in a legislative district or body. Gerrymandering involves dividing a state or a country into election districts so as to give one political party a majority in many districts, while concentrating the voting strength of the other party into as few districts as possible. Both manipulations types deny Malaysians the fair representative government they deserve. These manipulations entrench racial divisions, unfettered corruption, and the removal of checks and balances in the system of government. Essentially these two manipulations force political parties to win the right number of seats in the right locations.

What are the consequences of unfair and unconstitutional redelineations, as gazetted by the federal government in March 2018? Malapportionment robs Malaysians of the government they deserve, and the 13th general elections (GE13) in 2013 clearly showed how the majority of Malaysians did not get the government they wanted. Opposition bastions largely remain in urban areas, with the exception of Kangar and Johor Bahru.

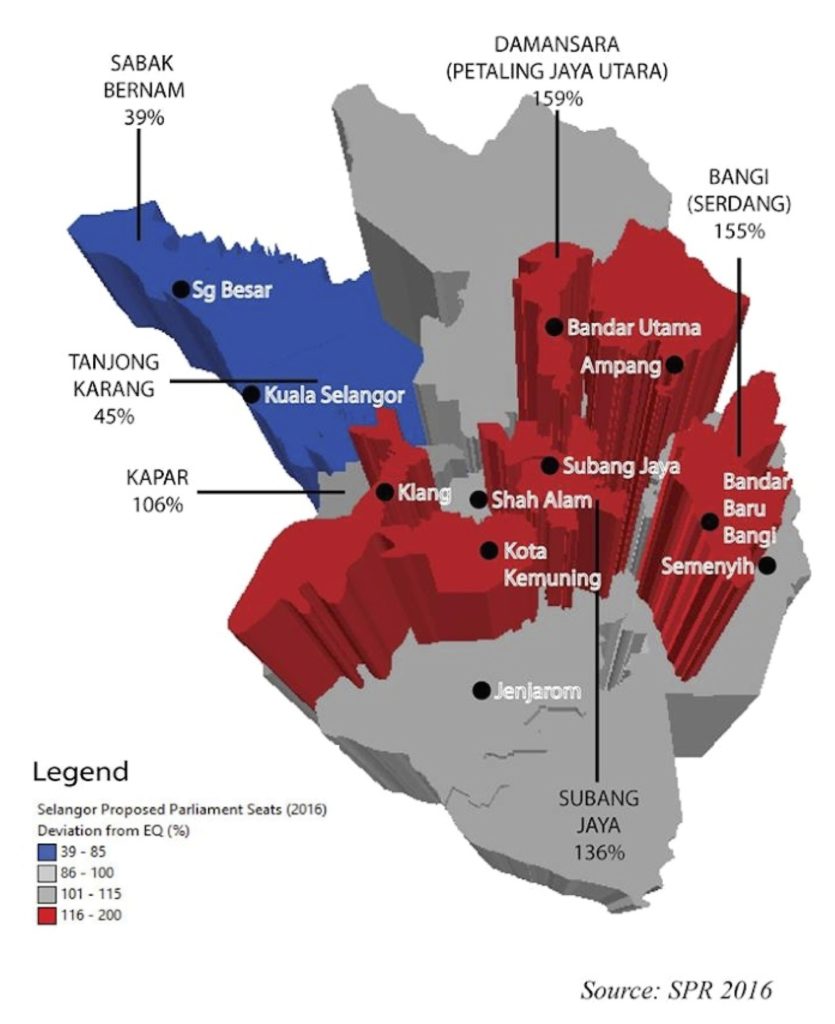

It’s theoretically possible to form a federal government in Malaysia with just 16.5% of the popular vote. The short- and medium-term consequences of this possibility demoralises voters, discouraging them from participating in the democratic process. The high voter turnout and the desire for change were key determining factors in defeating the unfair redelineation exercise of 2003 in states like in Penang, Kelantan, Selangor and KL in 2008 and 2013. The 2018 redelineation exercise is sending the same sort of message to voters: that voting to change the government is not worth the time. The same exercise creates voluminous wasted votes in opposition-packed areas. For example, newly reconstituted seats of Damansara and Seputeh will hand DAP thumping majorities (while denying any chance for MCA to regain the seats). By packing opposition votes in super seats, DAP may gain super majorities without gaining additional new seats in Selangor and KL.

Recent delineations for Selangor have resulted in supersized parliamentary seats, mainly affecting the opposition coalition, and fail to address malapportionment. Seats with deviations less than 85% or above 115% represent over and under representation respectively. Gross malapportionment undermines one-man one-vote one-value principle. Old names of seats are in brackets.

Since 1984, when Dr Mahathir was prime minister, redelineation exercises have been responsible in accentuating Malaysia’s racial divisions. Racialised gerrymandering is conducted according to the BN government’s preferences. Former EC chief Rashid Abdul Rahman (now a member of Dr Mahathir’s opposition party) admitted the redelineation exercise he conducted was to strengthen “Malay power” in 2013.

However, Tindak’s research and readings of the 1984 and 2003 redelineation exercises disproves the claims of Rashid. The 1984 redelineation exercise resulted in more Malay-majority seats created than other racial-majority seats, based on the view that Malays supported Mahathir’s UMNO. But Anwar Ibrahim’s sacking in 1998 and the consolidation of Pas as the biggest opposition party in 1999 reflected a dramatic shift in Malay voter preferences. The 2003 redelineation exercise resulted in more mixed seats, which was seen as a way to weaken Pas’ Malay support. Such racially-based gerrymandering was to strengthen UMNO’s Malay power base over its rivals such as Pas, and Anwar Ibrahim’s PKR. Racial gerrymandering continues to be a lifeline for a government that plays the racial politics that have defined Malaysia since colonial times.

During the redelineation process for Sabah and Peninsular Malaysia, the EC drew out 13 new state seats for Sabah (as Sabah’s constitution called for increased representation) in 2016. Although the EC completed its proposed boundaries of 13 new seats by 2017, PM Najib surprisingly did not table this proposal in Parliament in 2018 (along with the peninsula’s boundary changes). As Sabah state elections are due soon, some lawmakers argue that Sabah state elections could be deemed unconstitutional as 13 new seats have yet to be approved. Analysts argue the proposed creation of 13 new seats might benefit BN’s main rival in Sabah, Shafie Apdal’s Warisan party. There is an on-going court case to repeal the enactment calling for additional seats in the Sabah legislature. The situation in Sabah is a unique case, where there is no rush in implementing the new borders thanks to evolving Sabahan voter preferences.

The redelineation exercises of 2016 to 2018 further erode Malaysia’s democratic institutions, demoralising voters, preserving the urban-rural divide along racial lines, and suggesting the impossibility of change. While the redelineation issue may sound gloomy, the redelineation process itself may not be as significant to the election’s outcome as some argue. Multi-corner fights in tightly held seats, the size of the voter turnout, and electoral irregularities such as dubious voters and postal voting integrity are bigger factors in GE14’s outcomes. The lengthy period taken for this redelineation may mean its original intent can backfire, as Malay, Indian and indigenous Sabahan voter preferences are changing. Tindak Malaysia firmly disagrees with the BN coalition’s attitude on redelineation as it’s another attempt to fix the electoral outcome for GE14. However, it’s the voter that ultimately decides the impact this redelineation will have on GE14.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss