Malaysia’s once exceptionally stable political order has been upended. A new phase has been entered in the long struggle over who formally exercises political power over the state—and to what end.

For six decades following political independence in 1957, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO)-led Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition monopolised power. This ended in 2018 when the multiethnic Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition won government from opposition. Yet the PH government collapsed within two years when one of its key members, Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, withdrew to form the Perikatan Nasional (PN) government with support from UMNO and other mainly ethnic Malay parties. The November 2022 elections have now produced a hung parliament, with Malaysia’s Agong (King) appointing PH leader Anwar Ibrahim as prime minister and inviting him to try to form a ‘unity government’.

Why such a rapid and momentous unravelling of the seemingly impregnable political stranglehold of UMNO and BN? And where is Malaysian politics now headed?

Ironically, the seeds of UMNO’s political demise were sown by the very political economy relationships and supporting ideology on which its dominance were founded. The formation and consolidation of BN, within which UMNO incorporated and subordinated ethnic-based Chinese and Indian parties, allowed UMNO to sustain its project of state-sponsored capitalism rationalised through racial and ethnic ideologies.

Yet the contradictions of this model created opportunities for new coalitions—both those seeking to transcend the paradigm of racial politics, and others challenging UMNO’s mantle for Malay representation.

The successful fostering of a Malay bourgeoisie and powers of a Malay politico-bureaucratic elite also laid the foundations for dynamic conflicts. The UMNO–BN political economy model generated rapid general upward social mobility in the 1970s and 1980s, despite social and political tensions between the interests of emerging oligarchs and officially espoused egalitarian development goals.

However, tensions subsequently heightened, especially during periodic economic crises—including the mid-1980s recession and the 1997–98 Asian Financial Crisis—and following BN’s adoption of neoliberal policies starting in the mid-1980s under prime minister Mahathir Mohamad and finance minister Daim Zainuddin. Privatisations and financial deregulation generated opportunities for select politically linked corporate elites to boost their wealth. According to Mahathir, this would promote a more competitive business class to maximise Malaysia’s economic growth and industrial transformation.

An increasingly unequal social distribution of the costs and benefits of capitalist development transpired and intra-UMNO factional struggles over state patronage and corruption became rampant. Accumulation strategies of the most politically-favoured BN-linked conglomerates prospered, while others within the business class became more disgruntled. Meanwhile, the costs of utilities and services, now under the control of BN-linked conglomerates, mounted for lower-middle and working classes. This included oligopolistic charges by highway concessionaires, electric power producers, operators of urban light rail, and waste disposal providers. Crucially, conflicts over inequalities increased within and across ethnic groups, and the BN frameworks of ethnic representation became increasingly incapable of containing such conflict.

There were attempts by successive UMNO–BN governments after the Asian Financial Crisis to consolidate key national assets—including utilities and services under state-linked investment firms. Prime minister Najib Razak also reached out to voters via direct cash payments. Nevertheless, cost of living concerns persisted. Corruption allegations in 2015 over US$4.5 billion missing from state investment company 1Mayalsia Development Berhad (1MDB) was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Revelations of the extravagant lifestyle of Najib and his family highlighted the stark inequality between UMNO leaders and commoners.

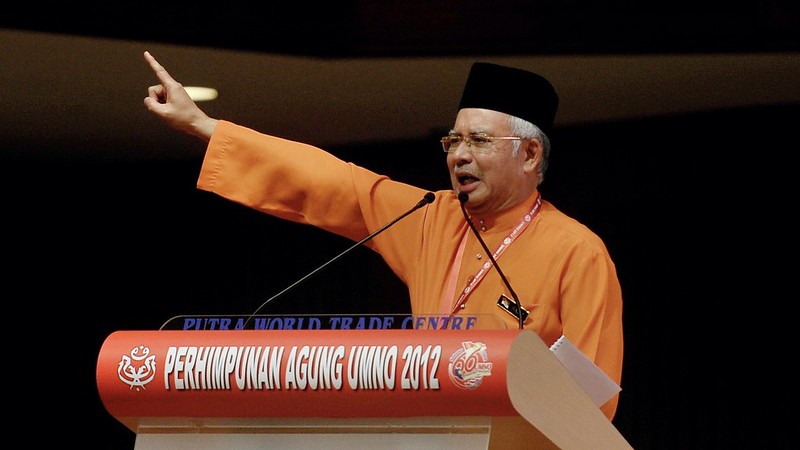

Former prime minister Najib Razak at the 2012 UMNO General Assembly (Photo: Prachatai on Flickr, Creative Commons)

This fuelled two different challenges to the prevailing political order. One was from forces advocating liberal and social democratic reform, including an end to corruption and other state power abuses and abandoning the racial affirmative action that increasingly bolstered oligarchic wealth while working-class Malays fell behind. Another was from religious and ethnonationalist forces who stridently endorsed Malay political supremacy and affirmative action, and special Malay cultural rights. They attacked UMNO as morally corrupt and a weak custodian of Malay interests and identities.

Political fragmentation and polarisation gathered momentum, but not to the exclusion of creative new civil society and political party coalitions. Ultimately, this made it possible for the election of a PH government in 2018 comprising a mix of liberal and social democratic reformers alongside moderate Malay nationalists. Yet ideological differences within PH over the vision of a ‘New Malaysia’ helped shorten its tenure.

Nevertheless, voter disenchantment with UMNO escalated at the 2022 polls. UMNO won just 30 of the 191 lower house seats it contested, and the 222 on offer. PH secured most seats with 82, PN next best with 73. Remarkably, PN has supplanted UMNO as the leading political coalition laying claim to Malay representation. Its rise—like that of PH—was born out of dissent against UMNO and its model of political economy. As we’ve noted, the contradictions inherent to that model generated the conflicts out of which coalitions to the left and right of UMNO—PH, and PN—have now become electorally pre-eminent.

The UMNO Building in Kuala Lumpur (Photo: Purnadi Phan on Flickr, Creative Commons)

This throws up fascinating new possibilities for—and challenges to—political change in Malaysia. UMNO cannot take government for the foreseeable future, but what are the prospects of reform in a ‘unity government’? Will it have the capacity or inclination to dismantle or transform state power established and entrenched under UMNO?

Following Anwar’s appointment as PM and the Agong’s invitation to try and form a ‘unity government,’ other parties—including Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS) with 23 seats and UMNO expressed interest in joining such a government. Indeed, a two-thirds majority of seats appears may be possible, which would provide a buffer for the new government in the lower house.

Despite calls for healing and unity by Anwar, the recent election was polarising, with racialist hate speech prominent. Deep social fractures remain. Battle lines between PH and PN will likely sharpen now that the former will have most representatives under any configuration of ‘unity government.’ Moreover, UMNO reluctantly threw its support behind this government in the sober recognition it was the only immediate hope of political influence—if only as a spoiler to block unwanted reforms.

Thus, while post-pandemic economic recovery and inflation will likely be the new government’s priorities, UMNO’s ‘Malay agenda’ will remain central to policy debates—not least in trying to shape the new government’s responses to economic challenges. PN’s base in an extensive organisational ecosystem and online activists from civil society can also be guaranteed to keep pressure on the government, members of parliament and state authorities to ensure its more radical agenda gets highlighted. PH may draw tactical lessons from the 2018–20 experience in government, but that it has a more liberal, socially democratic and non-Malay support base than other coalitions in parliament still renders it a natural target of attack for the ethnonationalists that dominate PN’s.

The return of Anwar

Anwar has a chance to bring stability and reform, but he'll be on a short leash within his coalition and besieged by race-and-religion politics.

PH may also see potential to shore up its Malay/Bumiputera ‘credentials’ to legitimise its power within a ‘unity government’. Judging by the response of the Malaysian share market following the confirmation of an Anwar-led ‘unity government’, influential capitalists might welcome this arrangement too. Yet this same political accommodation will contain unavoidable tensions—especially if PH attempts to implement institutional reforms affecting patronage networks through government projects and government-linked companies (GLCs).

During its last attempt at government, PH discovered how difficult it is to translate winning office into reforming state power. In a so-called unity government, such a project looms as even more difficult. The new parliament comprises a complex cocktail of forces and interests. Competing liberal, democratic, and anti-democratic ideologies will mediate any reform to state powers underpinning Malaysia’s distinctive model of capitalism. Important changes cannot be entirely ruled out, but it is hard to envisage ‘unity’ around reforms that fundamentally erode state powers rationalised on ideologies of race and ethnicity.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss