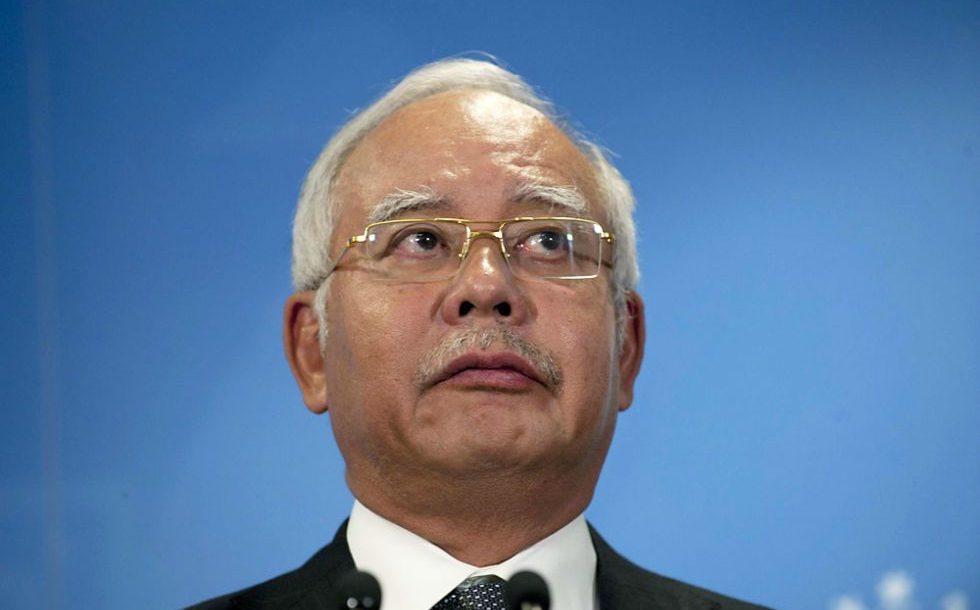

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak is courting some of the biggest Chinese tech companies in a bid to foster the country’s digital economy, but his own administration’s culture of corruption might prove too much of a drag on innovation, Teck Chi Wong writes

In an official trip to Beijing early this November, Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak tapped Alibaba Group founder Jack Ma as an advisor to the Malaysian government on the digital economy.

The digital economy is now a major source of economic growth for the world. It also offers new opportunities for entrepreneurs to innovate and enhance social welfare and efficiency. This is something that Malaysia cannot miss if the country wants to transform itself to a knowledge-based developed economy.

But the digital economy is also proving disruptive. It changes how businesses operate in many sectors, and in the process, old physical intermediaries, which firms in the past relied on to deliver goods and services to consumers, are eliminated. Replacing them are new online intermediaries which are mainly multinational corporations that exchange across borders directly with consumers.

This change will have implications for global income distribution. As wealth is shifted across borders towards innovators, those in traditional industries, particularly workers, are the main casualties. Such impacts are evident in the disruption brought by Uber, and it is unsurprising that taxi drivers have been protesting, rightly or wrongly, against the ride-sharing service provider.

This does not, however, suggest that the digital economy should be responded to with protectionism. This is akin to throwing the baby – the benefits and the improvement we enjoy that come with the digital economy – out with the bath water. In the case of Uber, such disruption proved to be a catalyst in pushing for a long-awaited reform to Malaysia’s taxi industry, which is infamous for its low efficiency and domination by crony companies.

Najib’s administration is right in trying to embrace the so-called ‘innovation tsunami’. It is important for Malaysia to foster its own cohort of entrepreneurs who can compete on the global stage and capture opportunities offered by the digital economy. Only then can Malaysia stay competitive and create more high-paying jobs for its citizens.

In October, Najib announced that 2017 will be ‘the year of the Internet economy’ for Malaysia. To cultivate local entrepreneurship, the prime minister, in his budget speech one week after, said that the government will allocate RM162 million for programs such as the e-commerce ecosystem and Digital Maker movement as well as the introduction of the Malaysia Digital Hub.

To woo foreign technology companies, Najib also unveiled a plan to introduce the first Digital Free Zone in the world, which ‘will merge physical and virtual zones, with additional online and digital services to facilitate international e-commerce and invigorate internet-based innovation’. More details are expected to be announced when Ma visits Malaysia in March next year.

But for Malaysia to unleash the full potential of its local talents in the digital economy, much more needs to be done, particularly in regard to the brain drain from the country and ethnic based policies. And there is the very real possibility the Najib Administration itself may become a drag to such an ambition, given that the prime minister is now implicated in the unprecedented 1MDB scandal, in which billions of public funds were allegedly siphoned away from a state-owned investment company.

The scandal highlights how rotten the political culture is within the ruling elites – not only at the top, but also down to the grassroots level, where many UMNO divisional leaders have become instantly rich through lucrative government contracts and connections.

As American economist William J Baumol argues, this will undoubtedly affect the reward system of the economy. More resources and talents will be diverted to activities such as rent-seeking and corruption because they are more attractive and lucrative. Less will be invested for productive activities such as innovation.

Unsurprisingly, in 2016, Malaysia has been ranked by The Economist as number two in the crony-capitalism index. Many of the country’s tycoons earn their fortunes from industries which are prone to rent-seeking, such as telecoms, natural resources, real estate and construction, rather than those which are highly competitive. Malaysian industries are also struggling after the failure to leapfrog to a technological frontier at an early stage of development and are now facing competitive pressure from other low-cost countries.

To change the reward system of the economy to one which encourages innovation will require an overhaul of Malaysia’s political system. But reforms of such magnitude are unlikely to be initiated by Najib and his ruling party, whose integrity and credibility are now already shattered by the 1MDB scandal.

Teck Chi Wong is a former journalist and editor with Malaysiakini. He is currently pursuing a Master of Public Policy at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss