Amid record-high COVID cases, Malaysia’s newest Prime Minister from UMNO, Ismail Sabri Yaakob, was sworn in this past week. More than three years after its National Front government was voted out of power, UMNO, the largest party in the current government, regained the powerful prime minister position without an election. The change evokes a strong sense of political déjà vu, but how much is this a return to the politics of old? Here, I briefly assess the extent to which it represents a return to the pre-2018 reign of the National Front, a continuation of the most recent National Alliance government, or a new and unstable political reality. I also consider what the implications of the latest shift in the ruling elite has for the prospects of reform.

Malaysia’s political institutions: battered and circumvented

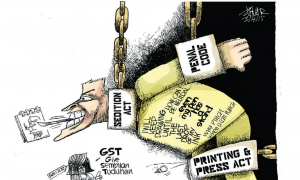

The appointment of the new prime minister comes during a bruising period for Malaysia’s political institutions. The 2018 elections brought an end to the decades-long rule of the UMNO-led National Front, but the victorious Alliance of Hope (PH) coalition government collapsed in less than two years. In its place, a fragile new government headed by Muhyiddin Yassin of the UMNO-breakaway party Bersatu brought UMNO back into the ruling coalition. For 17 months, he staved off a political reckoning by circumventing basic democratic institutions. By early 2021, with a declaration of Emergency assented to by the King, Muhyiddin halted elections and suspended parliament and state legislatures, ruling instead through his cabinet. The latter swelled to record size as he sought to shore up tenuous political support. Critical voices were punished, and all public assemblies banned—perhaps most vividly shown when riot police were deployed after opposition MPs gathered outside the suspended parliament. Yet even with these tactics, Muhyiddin was unable to stem increasing public discontent with his government’s leadership, a highly public reprimand from the King for avoiding parliamentary debate on the Emergency, and eventually a loss of support from UMNO.

Ismail Sabri’s unlikely ascension to prime minister has not deviated from the new COVID-era political normal. It marks the second time in a row that a prime minister has been selected, and governing coalition formed, without an electoral mandate or vote of confidence in parliament. Instead, Malaysia’s MPs privately indicated their preferred candidate to the King, who then declared who was most likely to command the support of a majority in parliament. In both cases, the “winning” prime ministerial candidate was backed by a slim or ambiguous majority, comprised largely of parties that had been rejected by a majority of voters in the 2018 elections.

While the Emergency ended on August 1, constraints on public gatherings remain, and its institutions are still unprepared to resume full functioning. The government has still not developed a plan for a full in-person or remote sitting of parliament, instead opting to cut down length and frequency of meetings and the number of MPs who can attend. The Elections Commission has not announced a plan on how to safely hold a national election during the pandemic, despite a number of countries successfully doing so.

An UMNO-led coalition government, but different

In this context, UMNO’s return to power without election simply seems to cap a period of democratic regression in Malaysia. But since UMNO last held national power, Malaysia’s political landscape has changed in significant ways. First, the new prime minister came to power on the thinnest of margins, with a support coalition that is almost exactly the same as his predecessor. At the time of writing, Ismail Sabri commands the support of 114 MPs—just three more than a simple majority in parliament. It is a far cry from the commanding support that UMNO’s National Front held for decades in power, or even from the solid majority that the Alliance of Hope (PH) government had until 2020.

Second, the well-ordered parties and coalitions that defined Malaysian politics for decades have fragmented. In contrast to the tight backing coalition that the party enjoyed for decades in power, UMNO’s new prime minister is backed by a mix of parties, regional coalitions, and individual MPs, with less allegiance to UMNO and even mutual antagonism. While UMNO’s internal divisions may be smoothed over by a return to power, several members of its top leadership, including current and former party presidents Zahid Hamidi and Najib Razak, have corruption cases still working their way through the courts.

The current permutation of government is still delicate and is contingent on rewarding backers with ministerships, patronage positions, and policy demands. It is too early to tell how (or whether) the new prime minister will successfully expand and stabilise his support. The government under UMNO is likely better positioned than its predecessor to hold together a coalition with a fresh prime minister. But in the near term, much political energy and focus will be spent on keeping together and expanding a fragile governing coalition. With a scheduled vote of confidence and budget deliberations looming, the new prime minister has two immediate tests to survive in the coming months.

Yet just as the current government is momentarily weak, so too is its opposition. Mostly comprised of parties from the former PH government, the opposition was sidelined throughout the Muhyiddin administration and lacked the venue of parliament to exercise oversight. Even though PH still controls a significant bloc of seats in parliament, its perennial prime ministerial candidate Anwar Ibrahim was unable to shift support to his side. For now, the public statements of the opposition suggest a conciliatory tone to the new PM, setting their sights on how to make gains in the next election, which must be held before July 2023.

Whither the reform agenda?

The need for political and institutional reform has come into even clearer relief over the past two years. Although it failed to implement many of its promises while in government, the Alliance of Hope (PH) coalition that briefly ruled after 2018, and Malaysia’s civil society organizations, have laid out comprehensive proposals for political and institutional reform.

An optimistic reading of events would see the instability and fluidity of Malaysia’s current politics as offering space to implement some of those ideas. The very tenuousness of the current government opens some avenues for reform-minded politicians to offer support in exchange for implementation of reform. At the end of his term, former prime minister Muhyiddin (allegedly in negotiation with opposition politicians) offered a number of reform proposals in exchange for the opposition’s support. Although the offer quickly fell apart, some of the proposals—including parliamentary reforms and equal allocations given to opposition MPs—suggest such reforms could become future bargaining chips for political support. Along those lines, the NGO Bersih has proposed that the opposition enter into a confidence and supply agreement with the government, ensuring a modicum of political stability while extracting reforms.

Although still hampered by COVID-justified restrictions, public discontent with the political situation and handling of COVID is increasingly visible. A white flag campaign saw Malaysians hanging flags to appeal for urgent food or financial aid; a newer movement called on Malaysians to hang black flags to display their discontent with the government and handling of the pandemic. In July, the #Lawan movement organised a protest in defiance of the bans on public gatherings. The appetite for political change appears stronger, especially compared to the muted response to the collapse of the PH government in 2020.

On the other hand, there is little to suggest that the governing parties or prime minister are interested in pursuing broad political reforms even during a period of relative weakness. UMNO has strong incentives to keep the opposition PH coalition at arm’s length while maintaining the habits of semi-democratic rule that were revived under Muhyiddin and his government. Similarly, new PM Ismail Sabri’s limited public track record does not indicate a reformist agenda. Prior to his rapid rise in the previous government, Ismail was a prominent figure in organising 2018 protests against ICERD, the UN convention on the elimination of racial discrimination, and made incendiary comments about the threat to Malay rights and supremacy by racial minorities and the majority ethnic Chinese party DAP. He is certainly not the only UMNO leader to have employed such rhetoric, but notably, he had not tried to depart from the mould.

National harmony: race, politics and campaigning in Malaysia

A new report analyses debates around social cohesion and a failed proposal for a National Harmony Commission in Malaysia in light of Pakatan Harapan's collapse

An uncertain future

UMNO’s return to power is itself not surprising. From a comparative perspective, former dominant authoritarian parties like the PRI in Mexico and the KMT in Taiwan did not disappear after national political defeat, but instead remain enduring and important political players. In the case of Malaysia, however, the return of UMNO and many of the parties voted out in 2018 was done without elections and was accompanied by a return to authoritarian tactics to quell dissent and ensure political support.

Judging by the outpouring on social media and on the streets, ordinary Malaysians are angry at the continuous politicking and elite political machinations that have occurred since 2020. This anger has been increasingly visible as the country grapples with economic downturn and escalating cases and deaths from COVID. The instability at the top, however, is not just a question of elite positioning. Instead, it has had real social, economic, and political consequences during a national and global public health crisis. The appointment of a new prime minister does not settle the simmering intra-elite conflict. Yet Malaysia already has the appropriate institutional framework—namely elections and the parliament—to not only negotiate these conflicts and ensure effective oversight of decision making, but also to provide an opportunity for ordinary Malaysians to provide an electoral mandate to a governing coalition.

The country’s political elites have revealed a worryingly loose allegiance to these norms and institutions over the last several months. A commitment by the new government to using democratic avenues to govern and prove mass support would increase the chance of effectively dealing with the significant challenges facing the country. But a commitment to playing by the democratic rules is unlikely to be realized any time soon. The promise of the “New Malaysia” that would emerge after the historic 2018 election has been delayed again indefinitely.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss