A recent report has touted the economic contributions of Grab and its related activities at nearly RM10 billion, or 0.5% of Malaysia’s GDP, in 2023. The foreword by Malaysia’s Minister of Digital Gobind Singh Deo praises the company for “promoting more efficient use of resources”, “creating a new wave of business opportunities”, increasing market efficiency, and “enhancing the lives of millions”.

Leaving aside the question of who exactly commissioned this report—it does not indicate that either Grab or the Ministry of Digital did so, or whether was independently commissioned—e-commerce, e-hailing and delivery services have undoubtedly increased the number of jobs in Malaysia. But it should leave one to wonder: have these sectors risen at a cost to our workers and future economic prospects and could we have done better?

Why e-commerce, e-hailing and delivery services

The reason for singling out e-commerce, e-hailing and delivery services is, as the report also highlights, their significant contribution to economic output measured in GDP and employment. Another reason is the sheer ubiquity of these services in Malaysia, especially in urban spaces where economic activity and populations are most dense. The last reason is their utter simplicity. At the heart of it, these services move goods and passengers from one location to another and allow people to sell their goods or labour within this giant digital switchboard. A similar report on Grab in Thailand—which found its contribution being 1% of 2023 GDP—was released within the same month, making this analysis more relevant to regional developments as these platforms have engulfed much of Southeast Asia.

The closest category for encompassing these three business types would be the platform-based gig economy (PBGE), which has been defined as “labour markets characterised by platform-enabled independent contracting, providing work that is often temporary, unstable and patchy”. For the remainder of this article, I will be using platform capitalism to include PBGE and e-commerce in the Malaysian context as I want to examine its spillover effects into the wider economy—just as the report attempts to do but for its narrow aims. (In discussing their digital economy and platform capitalism aspects, services like Airbnb, video streaming and social media will not be lumped in for analysis due to their differences in business model and operations. Its inclusion as part of the gig economy discussion will leave out freelance workers like those who provide graphic design and website services.)

Platform capitalism: a historical necessity

The entry of these types of businesses came about at a crucial economic juncture. The Malaysian state was looking to retrieve the golden years from before the 1997–8 Asian Financial Crisis when annual GDP growth averaged 8–9%. Aside from the rebound after the 2007–8 Global Financial Crisis, growth only averaged about 4–5%.

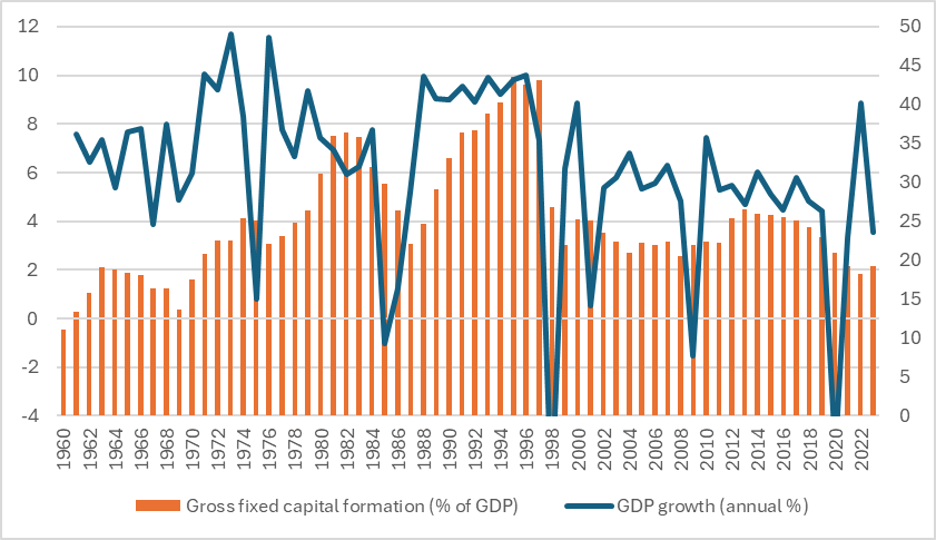

The slump in growth can be linked to the sharp decline in investment (measured as gross fixed capital formation). All of this was happening against the global economic background of manufacturing overcapacity and falling rates of return on fixed capital—machinery, equipment and production infrastructure). These declines were the likely drivers of Malaysia’s premature deindustrialisation and its accompanying fall in productivity growth—from a high of 6.7% in the early 1990s to a low of 1.1 in the late 2000s.

GDP Growth and Investment (measured as Gross Fixed Capital Formation in % of GDP). Data Source: World Bank (GFCF and GDP Growth).

If investment—particularly in manufacturing—could not be relied on to drive economic expansion, the engine of consumption could be fired up instead. 2012, when both Grab and Lazada were launched, also happens to be the year that the Najib government launched its digital economy initiatives. As Nick Srnicek observes in his book Platform Capitalism, the rise of the platform economy is linked to its reliance on excess capital and its “generating of monopoly rents into actual financial returns”. In other words, a key function of these industries is to soak up unused capital—that has few profitable places to go globally amid a worldwide decline in the profit rate—and generate fees as their primary source of revenue. Now e-commerce, e-hailing and delivery services are ubiquitous components of Malaysian life, whether you are a consumer or an employee of these firms.

Gains(?): some employment, and a whole lot of consumption

What has definitely been gained is the jobs generated from platform capitalism—and, more than that, drawing in people who wouldn’t otherwise be in the labour force. These people were likely to have never sought formal employment or have been taken on at formal-sector jobs for very low pay. Most Malaysians have anecdotes of people who have vocational qualifications or bachelor’s degrees doing e-hailing because it pays better than what they were trained to do. Data from the Department of Statistics Malaysia showed that the number of self-employed workers grew from approximately 1.9 million in 2011 to a high of more than 2.8 million in 2018, now settling at about 2.1 to 2.3 million in the 2020s. Given that the department classifies many of these riders and drivers as self-employed (or “own-account”) workers, the surge is likely explained by the emergence of the three sectors: e-commerce, e-hailing and delivery.

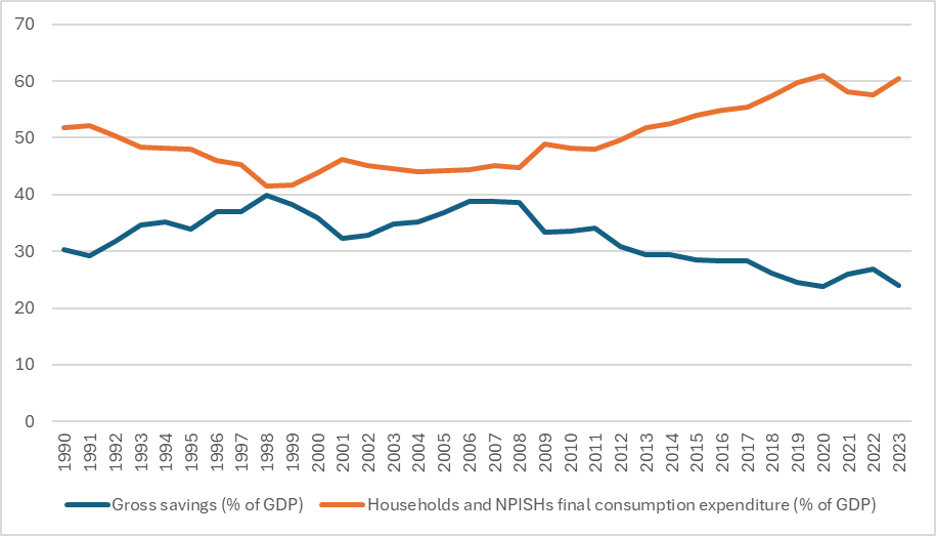

The other thing that has gone up is Malaysia’s overall consumption as a portion of GDP (excluding real estate purchases), which rose from 50% in 2012 to 61% in 2020. This is mirrored in the explosion of services relative to other sectors. National data shows that services nearly doubled from 2011 to 2019 (RM459 billion to RM860 billion) while manufacturing only grew from RM212 billion to RM324 billion or an increase of almost 50%. One estimate shows that the e-commerce sector contributed about 7–8% of GDP before the pandemic and now more than 13% in the early 2020s.

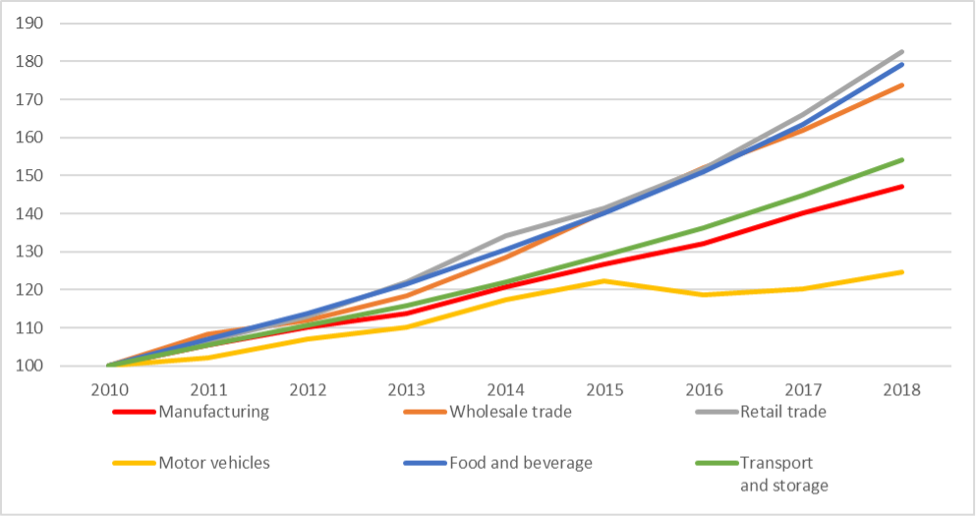

While the recent report on Grab does indicate the sector’s contribution towards “demand for petrol, vehicle maintenance and repair services”, there seems to be no evidence of a decisive increase in car or motorcycle sales based on the data from the government and the Malaysian Automotive Association. The graph of official data below confirms there is decent evidence that the gains are largely confined to the service sector and do not spill into manufacturing through increased vehicle purchases.

Gross Domestic Product by Kind of Economic Activity at Constant Prices, Malaysia (2010=100). Data Source: Ministry of Economy (National Accounts).

Gross Savings and Household Consumption. Data Source: World Bank (Households and NPISHs final consumption expenditure and Gross savings).

Who paid for the gains?

The money for this consumption came from all layers of Malaysian society but is likely drawn most heavily from the upper and middle classes—the “T30” in the parlance of the Khazanah Research Institute (KRI)—and those who attempt to spend like the middle class (their “M50” category). These two broad classes would have the disposable income to purchase more expensive goods, food, delivery and e-hailing services.

Where in the past one might just drive out to have dinner (and maybe spend RM2–3 on fuel to get there), now one pays significantly more (upwards to RM5–10) for the convenience of having it delivered to your doorstep. These labour-saving services allow for anyone with the financial means to have a virtual butler of sorts—getting food, goods of all kinds, transportation and even a variety of tasks done (GoGet for instance)— through platform capitalism.

Malaysia’s new struggle over state power

The UMNO era is over, but its political economy model and the social conflicts it created still set the terms of the new politics.

On top of all this, only a fraction of these new economic activities and revenues have trickled down to what KRI calls the “B20” (i.e. those who “can only fulfil their basic needs”) households who in all likelihood supplied the labour—delivery riders, e-hailing drivers and small food vendors—for this consumption. Even if these platforms only take a small slice of the commissions on these services—a whole host of them don’t even consistently turn a profit—it would not negate the fact that these workers do not earn a dignified wage and put their bodies at risk to acquire it.

What Malaysia lost, and could have had

The Grab report was released in February with very little public interest (at least from what can be seen on various social media). I suspect that is because the company’s achievements are nothing to be celebrated in social terms as the Malaysian government is busy looking to promote high-skill jobs, increase wages and give people better living standards.

It’s easy to see platform capitalism as a win solely on the increase of economic activity and overall employment created with e-commerce, e-hailing and delivery services. Yet the government’s own survey data reveal that a majority of workers in this sector are dissatisfied with their jobs. One could even say that some sections of the government are uneasy with this economic model given the persistent attempts to address underemployment and the national skills shortage. It is becoming increasingly evident that the value that platform capitalism brings to the table may not last or have as much impact as initially supposed.

These industries came about just at a time when they would essentially save the Malaysian government from having to deal with underemployment and the lack of meaningful job opportunities. They saved the government from needing to make an expensive and painful transition to bring the local workforce back into labour-intensive manufacturing, upskill Malaysian youth, and ultimately to pay them better.

Where does it go from here?

The lead author of the report on Grab’s role in the Thai economy told the press that “the platform economy is inevitable”, and it may certainly be the case given the global forces of financialisation. According to a recent KRI report, as Malaysia transitions from “industrial to finance capitalism”, what we get is an economy that “combines flexible labour markets with the expansion of credit … to sustain consumption in the face of stagnating real wages”. Platform capitalism seems to fit the bill almost exactly.

Yet this should not distract us from the social and economic consequences of continuing this system. Even if one wants to be generous and consider PBGE and e-commerce as a stopgap measure, it should not overshadow the lingering problem of low and stagnant wages across the economy, and the role of debt in keeping the flywheel of consumption turning.

But more importantly, where could deepening platform capitalism even take us in ten or twenty years? How soon will these platforms reach their maximum users and revenue and subsequently see their profits stagnate or decline? Would it ever be able to offer its riders and drivers a stable and secure career ladder? What would the debt situation of many middle-class aspirants look like? The bleak reality of reproducing this system and having a sizeable number of people become “their own boss”—how many platforms advertise riding or driving for them—is that we as a society have locked away a better future for many among us.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss