At the end of 1992 after the dissolution of powerful friend the Soviet Union, the Ho Chi Minh National Political Academy, a major organ of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) with responsibility for ensuring continued CPV rule, assigned its Institute of International Relations to study ASEAN countries and their political systems. When the report landed on the desks of CPV comrades they read that ASEAN governments were pro-West and anticommunist. But what came after was reassuring. ASEAN governments, the report stressed, are “determined to defend their ruling regimes, and refuse to share power with the people”. Moreover, the nation-building formula of the ASEAN states, consisting of an “export-oriented market economy, limited democracy, and even authoritarianism in some countries” was not in essence different to Vietnam’s. Having completed its homework, Vietnam joined ASEAN in 1995.

The spread of market Leninism from China into Vietnam and then Laos was a powerful emollient, helping bringing about peace in a region previously wracked by the bloodiest conflicts of the Cold War. It was a development warmly welcomed by Singaporean diplomats, who emphasised, in the words of senior diplomat S. R. Nathan, that “we were not anti-communist, we were non-communist”. Singapore’s elder statesman and former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew began to visit Vietnam frequently and remains revered there. Thailand, eager to bury the memory of its role in the Vietnam War as America’s staunchest ally, similarly leapt on the opportunity to bring the communist states into the fold, launching its “battlefields into market places” initiative.

These policies accelerated the emergence in Southeast Asia of what Nicole Jenne has called a “no war” community: a group of nations with relatively low expectations of interstate conflict, based on a pragmatic recognition that each has a low capacity for conventional warfare.

In a recent article in Democratization, I argue that in mainland Southeast Asia, this “no war” community has been the foundation for something altogether less wholesome: an authoritarian security community, a group of contiguous states that collude in transnational repression and illicit cross-border business, and share authoritarian governance techniques and mutually legitimise their authoritarian rule.

The authoritarian security community (ASC) theory offers an additional transnational mechanism for understanding, beyond domestic political explanations, why Southeast Asia has been part of the global decline in democracy.

While there is variation in how to characterise that decline, and how serious it is in historical terms, a turn away from liberal democratic forms of governance worldwide is one of the major contemporary trends in international politics. The decline comprises both a deterioration in democratic institutions and governance in established democracies and in what limited democratic practice exists in autocracies. These parallel trends are reflected in falling scores across a range of democracy rating indices such as the Freedom House Index, the Bertelsmann Transformation Index, and the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. This decline is thought to have begun around 2006.

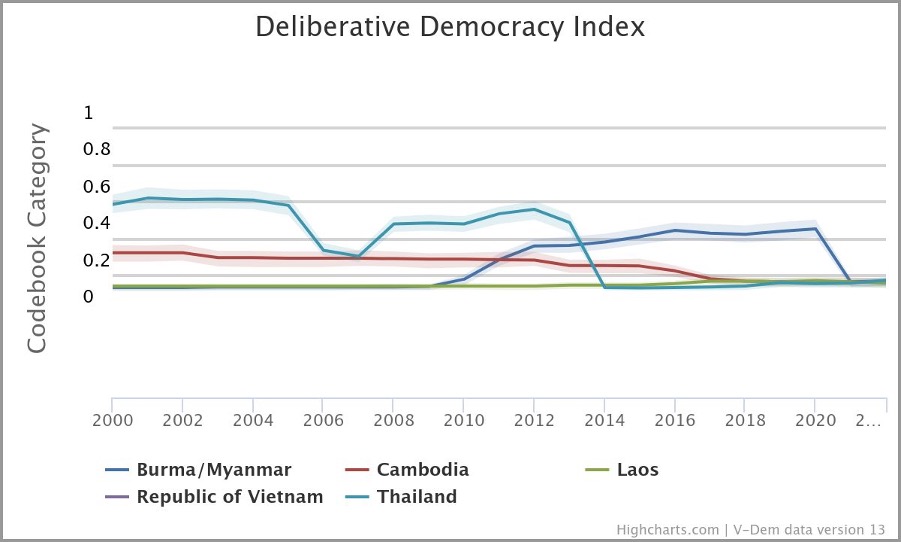

The decline of democracy has been significantly more serious in mainland Southeast Asia, compared with the maritime states. Between 2005 and 2023, the average score for among significant maritime Southeast Asian states (the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia) on V-Dem’s Deliberative Democracy Index declined by 9%. Over the same period, average scores across five mainland Southeast Asian states fell by 46%. A comparable maritime–mainland gap can be found in the democracy scores of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index: between 2006 to 2022 maritime Southeast Asian states slipped by 5%, while the analogous scores for the mainland states fell by 9%.

Looking more deeply into the trend data reveals that the scores for the two formal communist party-states, Laos and Vietnam, have remained relatively constant, albeit low. The states which have produced the falling regional-average scores are Thailand, Cambodia and Myanmar. As the figure below shows, Thailand and Cambodia especially have evinced the greatest downward shifts, moving back towards the consistently low scores of their one-party neighbours since 2005.

The local sources of authoritarian learning

So what has happened in mainland Southeast Asia? Many might immediately hypothesise that close proximity to China offers an explanation. But caution is warranted before blaming China. China’s role as a “Black Knight” purveyor of authoritarianism is in fact considerably nuanced, and the scholarly literature is ambivalent. While one school of thought strongly argues that China wants a world in which authoritarian regimes are given greater respect and deference and is actively exporting a model to achieve this, another observes that it is pragmatic and regime-neutral in diplomatic practice.

The characterisation of China as a “passive Black Knight” makes sense of this apparent dichotomy. While China will shore up old autocratic friends, make knowledge about authoritarian governance available, seek to remould international institutions and hope its example wins adherents, it will not actively promote or foster regime change.

As a passive Black Knight, China certainly played a critical role in facilitating Cambodia’s transition from competitive to hegemonic authoritarianism after 2013. After a near election loss, Cambodia’s autocrat Hun Sen closed down democratic space, banned independent media and ultimately, in 2017, dissolved the main opposition party. To minimise delegitimising criticism from the West, and replace withdrawn foreign aid and assistance, he significantly strengthened relations with China, which boosted military and economic assistance.

But notions of a “China Model” exerting a powerful pull on Southeast Asian leaders need to be kept in perspective. Prayuth Chan-ocha’s junta government in Thailand largely used references to Xi Jinping’s “China model” to justify decisions already made—that is, instrumentally, in the same way Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban cited Russia, China, Turkey and Singapore as models to legitimise decisions of indigenous origin.

The survey evidence for Southeast Asian nations wishing to emulate China is also weak. In the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s annual State of Southeast Asia survey between 2020–2024, respondents who had stated they trusted China were offered the option of selecting “my country’s political culture and worldview are compatible with China’s” as the reason they trusted China. Over five years only an average of 16% from mainland Southeast Asian countries selected this option.

In fact, looking within Southeast Asia itself for transnational authoritarian flows provides equally persuasive evidence. As I noted that the outset, ASEAN has provided an inviting and indeed nurturing environment for authoritarian regimes. Beyond ensuring that domestic repression remains out-of-scope for discussion under ASEAN’s non-interference principle, Southeast Asian autocrats learn from each other.

Hun Sen confessed to emulating the ways in which Indonesia’s Golkar under Suharto, and Malaysia’s UMNO under Mahathir, had strengthened their regimes by forming strong patron–client relationships between the ruled and the rulers. Singapore, an economically successful authoritarian state, is another model for ASEAN states. Cambodia and Vietnam have all studied Singapore’s management of “rule of law”, which has frequently been a method of silencing critique. (Strikingly, so has China, establishing that the flow of authoritarian influence has not been only one way.)

This learning has also occurred within the Mekong community of states. In 2017, Hun Sen publicly exhorted Cambodia to examine Thai laws used in Thailand to dissolve political parties— and within a month the Cambodian parliament passed such amendments.

In actual fact, it is within mainland Southeast Asia that transnational authoritarianism has been most conspicuous, paralleling democracy’s more precipitous decline. Ample evidence suggests the later-joining Mekong members of ASEAN—Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam—have extended ASEAN’s illiberal practices to a new level of subregional collusion, linking up with founding member Thailand in the process.

Crime (for security forces) and punishment (for dissidents) across borders

Two phenomena illustrate this deeper level of illiberalism, and both are intrinsic to the notion of an authoritarian security community: transnational repression and cross-border kleptocratic networks. The authoritarian regimes of the Mainland Southeast Asian ASC perceive transnational spaces as potential sanctuaries for regime adversaries and sources of democratic contagion. As such, they are prepared to cooperate to shut this space down, even to the point of tolerating encroachments on their sovereignty.

Since at least 2014, Mekong security services been active in transnational repression, including the assassination, disappearance, rendition and detention of dissidents, opposition party members and journalists. The region rates with sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East as one of the world’s hotbeds of transnational repression.

In 2021, Thailand was in the top 10 of origin countries globally practising transnational repression, with at least 25 cases known to have occurred on Thai territory. Reciprocity has been evident. A Thai anti-monarchist was kidnapped and “disappeared” in Cambodia in 2020 . Conversely, multiple Cambodian dissidents seeking refuge were monitored and apprehended by Cambodian security services permitted to operate on Thai soil. Five Thai anti-monarchists disappeared or were murdered in Laos between 2016 and 2018; meanwhile, a Laos dissident disappeared in Thailand in 2019. Cooperation between Vietnamese and Cambodian security forces may have as also occurred, with Vietnamese activists in Cambodia attacked with acid in 2017. Vietnamese dissidents were handed to visiting officers from Vietnam’s security forces by the Thais.

Thailand’s deinstitutionalised democracy movement

Thai conservatives have sought to prevent reformists from putting down roots in society—and it’s worked

Turning to cross-border kleptocratic networks, the 2015 discovery of mass graves in Malaysia exposed a massive people-smuggling ring spanning Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia, trafficking mostly Rohingya people numbering in the tens of thousands annually. International outrage resultied in the Thai government appointing police major general Paween Pongsirin to head a police investigation.

Paween’s investigation found 115 alleged offenders, including four officers from Thailand’s Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) and a navy officer. One of the ISOC officers arrested, Major General Manas Kongpan, was of three-star rank. The arrests of military personnel displeased key figures in the Thai junta government, including Prayuth and Pravit, who organised for Paween to be sent to Thailand’s restive and violent Southern provinces where the trafficking networks were particularly strong.

Fearing for his life, Paween fled to Australia, with the Australian government granting asylum. In a statutory declaration, Paween wrote that the “people who are seeking to harm me are at the highest level of military, police and government in Thailand. They have shown that they do not hold themselves to the law or the rules of the country”.

The price paid for peace

Mainland Southeast Asia’s security forces catalyse cross-border networks that offer opportunities for personal financial gain, and stabilise authoritarian governance via transnational repression. There is a circular relationship between the cross-border kleptocratic networks and the authoritarian nature of the regimes: on the one hand it is the weak accountability and rule of law that offers opportunities for graft and illicit trade, on the other, the criminal conduct creates incentives for the maintenance of authoritarian rule, since any move to accountability or stronger rule of law is likely to expose the culpable actors. Criminal networks may reinforce, overlap with, or emerge from the security-oriented transnational networks, who frequently act with impunity, confident in the knowledge that the higher echelons of the regime will mostly protect them in order to maintain a visage of invulnerability and a citizenry too cowed to protest or resist the depredations.

Few would argue with the proposition that Southeast Asia’s peace is a good thing. But if the price of peace is deepening repression, questions are warranted.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss