Julia Mayer recounts watching the ancient North Malaysian dance-theatre known as Mak Yong.

It is the ‘dry season’ in East Coast Malaysia, and it hasn’t rained solidly for perhaps a couple of weeks now despite the silver-lined promises of a shapeshifting sky. The ground is perennially parched, sending small spirals of dust in the wake of each languid step taken toward our destination. As time and space converge in this flat decaying coastal landscape, the heat renders one into the perpetual present with the future being at once unpredictable as it is unknowable. Time truly stands still, here.

Evening is ushered in by a gentle breeze abating the torrid thickness of the air, and upon our arrival, last minute preparations are underway inside the makeshift panggung, an open-walled space decorated largely with bamboo and bougainvillea, where the finale of the Mak Yong performance is to be held. This is the setting for the Kumpulan Mak Yong Cahaya Matahari’s Sembah Guru -literally ‘commemoration of teachers’, which occurs roughly once every nine years, and is performed over three consecutive nights with the final night explicitly dedicated to menghalalkan ilmu, the blessing of knowledge that has been handed down from one generation to the next.

Attracting a local audience of men, women and children swelling well into the hundreds, the final night traditionally carries a ritual element –main ‘teri -headed by the tok ‘teri, a shamanic healer. Tonight’s ritual is conducted by two healers, Pak Zul and Pak Omar, alongside master musician Pak Su Agel. Thepanggung has been transformed to represent ‘the other world’ where mythical creatures prey upon the weak and the vulnerable. At one end of the space is a balai, a kind of palace built out nipah palm, which symbolises, among other things, the abode of a poor prince who is forced to separate from his wife.

Next to the balai, are trays of offerings with one tray containing figurines made from rice flour and water which are said to represent creatures from the other world. Near the musicians, is an altar decorated with the traditional head-dresses belonging to each of the main characters in the Mak Yong repertoire, an orange coloured cake of glutinous rice is decorated with hard boiled eggs wrapped in tulle so often seen in Malay weddings, including a roast chicken to be shared among the performers at the close of the ritual. More trays bearing food, grains of rice, pastes and candles are located at the front of the panggung which are used to consecrate the performance space, including a large tub of water resembling a freshwater pond amidst the palm-frond foliage. The items inside the performance space are never isolated from each other, each has a critical role to play, an explicit purpose, in the ritual process.

I was invited to the Sembah Guru in Kampung Pengkalan Atap, Terengganu by Eddin Khoo and Pauline Fan of PUSAKA, a non-government organisation committed to encouraging the visibility and viability of Malaysian traditional arts at the level of the community. Supported by the Asia Foundation as part of PUSAKA’s Mak Yong community project, this particular three-night performance was largely realised by PUSAKA’s long associations with community spanning a couple of decades. As the performers remember and recall their lineage through embodying the inherited realm of the sublime, there is an equally strong a feeling that this could have been hundreds if not thousands of years in the making. It was this very sense of timelessness, ironically punctuated by the beat of the drums, that characterises this space, a space in which a reconciliation of the past depends not only upon the gazing, the witnessing and the recognition of the performers, but also of everyone about us.

Though I have watched the same group perform in a small theatre in Kuala Lumpur on several occasions, I was unprepared for the extreme emotional intensity invoked by the performers before their very own community. In a suburban theatre in Kuala Lumpur, it was the mutual fascination for the unfamiliar which propelled the intensity of those performances. Such a space, though, is as incongruous to the performers as is their artform to an audience whose exposure to Mak Yong lies generally in hollowed out versions for public consumption.

Whilst this sense of ‘not belonging’ in the theatre had certainly added to overall intensity experienced and was further perpetuated by the seemingly insurmountable divide between the performers and the audience, in the kampung, in their village, this intensity was magnified to epic proportions for a number of reasons. Firstly, it has been some time since a performance on this scale had been held, taking days if not weeks in preparation. Secondly, and perhaps most importantly, in this collision of worlds, the distinction between the audience and the performers was thoroughly blurred. Just as it is difficult to separate the dancer from the dance, so too, is it difficult to separate Mak Yong from its profound communal roots.

For more than a decade Che Siti Dollah, fondly known as Mek Ti, has mentored the granddaughters of the late Mak Yong legendary actress Che Ning. Whilst the three women Rohana Abdul Kadir (34), Che Yom (40) and Che Esa (44) started learning the dance-drama from their grandmother as young girls, it was through their Great Aunt, Mek Ti and her brother Pak Su Kadir, that they learnt the intricacies of the traditional art, maturing under their guidance. Now approaching their 80s, Mek Ti and Pak Su Kadir, who both trained under Che Ning, have decided that the time has come for a ceremony to officially acknowledge the new bearer of the family’s performance heritage.

Rohana has been chosen to shoulder this responsibility having made her mark over the past few years playing the contrasting lead roles of the Dewa Muda, a wealthy prince infatuated with the golden princess Puteri Ratna Emas, and his complementary opposite from another story, Dewa Pechil, the poor prince who is forced to separate from his beloved wife so that a wicked king can marry her. This role reversal, or rather, the duality expressed in these characters which are performed on separate nights, stands testimony to Rohana’s versatility and charisma as an artist. With her refined masculinity intermingled with a dignified yet humble demeanour, she is ready to submit herself toward becoming the knowledge bearer of her family’s tradition.

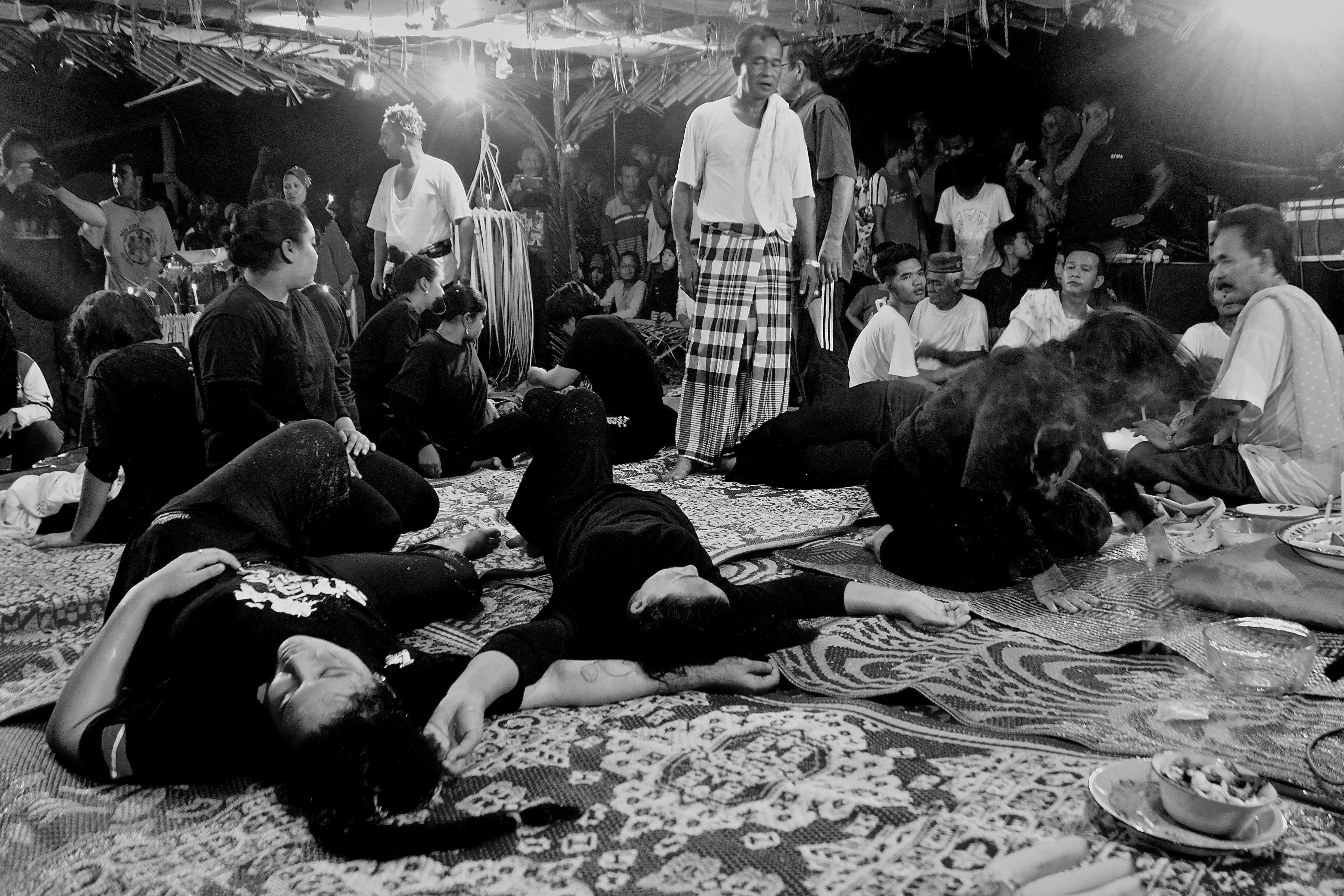

Seated upon a woven mat surrounded by the dayang, a chorus of maidens, Rohana gazes intently at the rebab. From the moment the spiked fiddle, the rebab, utters its first mournful wail, a different breeze altogether surges from within the arena, that of the ‘inner wind’, angin, from which the performers breathtakingly navigate through the heartrending pathos of longings and intense suffering. With the words offered to her -“Hari ni mu dengar baik…kerana mulah yang layak” (Listen carefully to my words today…for you are the one, worthy) – a powerful trance is triggered, and one by one members of the dayang fall into a trance – lupa-meaning ‘to forget’.

Yet in the doing of the forgetting which ranged from the flowing moves of the joget dance, to the plastic poses of the martial art form silat, to cowering animal-like down onto all fours, to impulsive and erratic head shaking, what is clear in this cathartic moment of being, is just how performers and the community continuously negotiated and renegotiated their personal emotional issues in this heightened state of awareness. Nor was this limited to the performers, for various members of the community had fallen into a trance outside of the panggun, and were carried inside to release, to let go and to forget.

To my astonishment, an older lady who had fallen into a trance-like state asked me to dance with her, and together, joined by the performers, friends, and other members of the community, we danced not to forget, but to ironically remember. This was a critical moment in the healing process, and, whilst the ‘work’ that this does for the community is ultimately the re-aligning of feelings of dissonance into a harmonious equilibrium, it was in the final moments dancing, that our ‘souls’ were cleansed and rejuvenated .

As an outsider, the nuances of this highly complex traditional art will forever remain mystery. Yet, the very power that the performers and musicians yield in drawing the likes of myself into a highly emotive state of pure joy and profound sadness to arrive at the point of perfect contentment, is what makes them undeniably true masters of Mak Yong. Indeed, part of me will always remain in Kampung Pengkalan Atap, and, as the dust settles on this unexpected extraordinary experience, I am left wondering how it is that I have always known the people who were with me on those long, dry, hot nights.

Julia Mayer is a Masters of Museum and Heritage Studies student at the Australian National University.

Author’s note: I would like to thank Eddin Khoo, Pauline Fan, Aiman Syaaban, Yana Rizal, Christine Yong and Susan Sarah John of PUSAKA for sharing their love and passion for Mak Yong and for extending the invitation to experience something truly unforgettable.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss