“Whoever becomes patron of a city accustomed to living free and does not destroy it, should expect to be destroyed by it; for it always has as a refuge in rebellion the name of liberty and its own ancient orders which are never forgotten either through length of time or because of benefits received.”

(Machiavelli, Chapter 5, The Prince)

As an undergraduate student more than a decade ago, I chose Machiavelli’s The Prince for my term paper in my introductory course for political science. It caught my curiosity because the author’s name was tied to deception and malevolence. Also, it’s shorter than Plato’s Republic. Through that exercise I realised that while Plato’s work is like a cool summer breeze that promised power through knowledge and reason, The Prince dragged readers back to the muddy complexities of reality.

It was more like a bucket of cold water thrown at readers than an eye opener. As a dissection of the familiar it can enable readers to analyse the underbelly of public life. More than a mere exposé, it equipped readers to focus on the movements, complexities, and art behind the struggle for power. Moreover, it released political ethics from the restraints of religious morality.

To allow Machiavelli to react to the centrality of leadership in Philippine politics (the Pangulo regime in Agpalo’s terms) I decided to translate The Prince into Filipino.

This endeavour is like reverse engineering. It required a credible understanding of the original in terms of its impact on political theory, and in relation to the author’s other works. Therefore, I utilised the following guideposts.

First, The Prince, originally untitled, earned Machiavelli a place in both the pantheon of political thinkers and the Papal list of banned works. This work’s value was due to the simplicity of its style and the profundity of ideas. The mindless usage of the clichéd yet often misunderstood quotations from The Prince remains an injustice.

Second, it’s neither a work of amorality nor sheer immorality. Instead, it is an application of humanist principles in politics. The Prince allowed readers to wear the shoes of a prince since it was originally meant to be read by one; shoes that Machiavelli weaved out of his understanding of reality and history, and his reassertion of Roman virtù against Christian virtue. It also raised the ideal of national unity for a fragmented Italian peninsula.

Third, the prince is intertwined with the state. The former takes a public form while the latter becomes partially personal. In other words, as was argued by Mansfield, the state for Machiavelli is something acquired, shaped, and personalised. Lastly, underlying The Prince is a warning for leaders not to underestimate the masses. They must be considered as a fickle entity with the power to make or break a prince.

Guided by this reading, I laboured to produce an indirect and meaning-based translation from three English versions.

I consulted the original text for crucial passages and concepts. Glossing over the drudgery of wrestling with several drafts, the entire process sandwiched me between two worlds of understanding power.

Building a bridge between contemporary Philippine politics and Renaissance Italy was pleasurably difficult.

The entire process gravitated around three contentious concepts, namely, virtù, fortuna, and stato. The first two can only be understood in relation with each other. In an earlier work I illustrated that while fortuna embodies reality with all its movements and surprises, virtù is the capacity to adapt to, and survive or even thrive under the former. It is not only about knowing how and when to act. It is also about the will and courage—the proverbial cojones—to control a situation and vie for power. Hence, a leader with virtù can lift fortuna’s veil and penetrate her.

If that sounded remotely sexual, then it showed an interesting dimension that I tackled in translating virtù. Specifically, virtù has two intertwined dimensions, namely, excellence and “manliness.” I emphasised the former to highlight its public administrative dimension, as well as Machiavelli’s attachment to Greek philosophy and its notion of arête (excellence). Linguistic nuances entailed certain costs like the loss of certain contextual meaning during transfer. Such costs were balanced out and paid for to ensure a coherent flow.

I faced a similar dilemma with the concept of stato. It can be translated easily into state, but this would invoke a modern meaning that Machiavelli did not share. Furthermore, estado is a foreign term. Rooted in a colonial past, it is estranged from everyday political discussions among ordinary Filipinos.

Hence, I chose the word bayan because it is endemic, colloquial, and a bridge to pre-Hispanic socio-political organisation. Furthermore, bayan refers to communities larger than a village (barangay), specifically a town and an entire country. It can also refer to the public itself, serving as the rootword for taong-bayan (the people), mamamayan (citizen), and pamayanan (community or polity). Hence, it allowed me to convey a leader’s practical integration into, and interdependence with the community. These factors ensure a direct appeal to the political psyche of ordinary readers; a condition exposed to the realities of clientelism and strongman politics in the Philippines.

At this point we must ask: who is a Machiavellian leader?

It is someone who knows that one’s position is based upon the security and welfare of one’s state. In other words, a leader is the state so long as one takes care of it as if it was one’s own body. If this is so, did the Philippines ever have one? Was it Marcos who, though serving as the prototype of a Philippine Machiavellian, pales in comparison to his contemporaries like Pinochet, Gaddafi, and Park? Was it Arroyo who survived despite her shaky legitimacy? Was it Estrada, Binay and the myriad of local populists who appealed to the welfare of the people? Or is it Duterte who is incapable of following Machiavelli’s principle for purging; that is, getting rid of the right ones so that the persecution can end quickly.

In addressing these questions, let me remind the reader that Machiavelli never used the word politics to refer to the activities he exposed. His attachment to Aristotle placed politics beyond mere power play. Moreover, his prince is an ideal type; a nameless composite of different leaders who tried to be great. Contrary to an embodiment of ruthless cynicism, Machiavelli conveyed ideals on leadership and civic life. This moves the question from who is to who should be a Machiavellian.

Duterte’s war on tongues

President Duterte’s use of Bisaya is a push back against Imperial Manila’s dominance. But it is also creating new hierarchies of language of its own.

Machiavelli’s resonance is not only with the issue of leadership. It is also a matter of citizenship. Should citizens see themselves as the state and be ruthless, crafty, and courageous in the acquisition and defence of their liberty? What is the implication of this paradigm on the liberal citizen whose actions are restrained by law? Through his eyes we can raise dangerous yet invaluable questions on power and civic life.

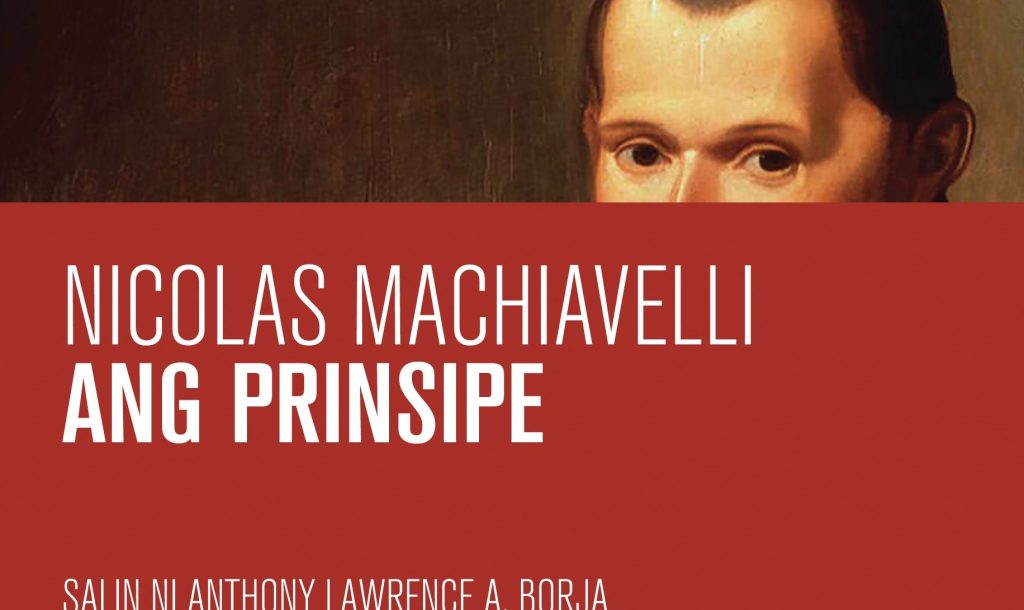

Nicolas Machiavelli: Ang Prinsipe was published in 2014 by De La Salle University Publishing House.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss