Despite suffering a series of grave blows, an ’emotional story’ keeps the controversial Buddhist group active and influential in Myanmar, Dinith Adikari writes.

Recently, Thulasi Wigneswaran wrote an excellent article for New Mandala discussing how to manage the Nationalist Buddhist organisation, Ma Ba Tha, while it is in decline. However, recent events in Rakhine State, such as protests in Sittwe as well as throughout rest of Southeast Asia, and increased hate speech on online platforms, seem to indicate circumstances parallel to those that first allowed Ma Ba Tha to launch itself as a tremendous political force.

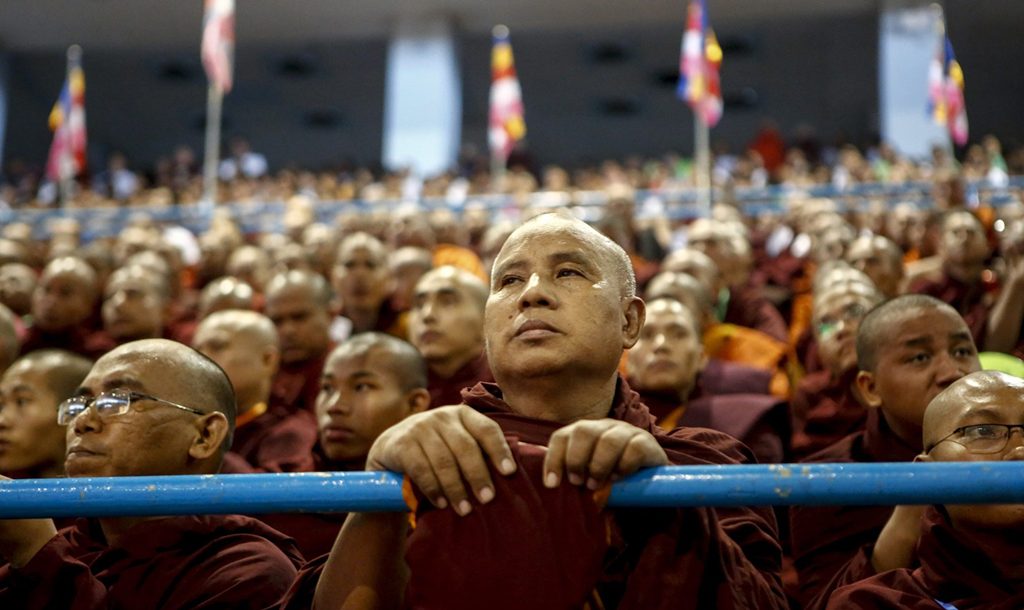

Ma Ba Tha or in its full English name, the Association to Protect Race and Religion, is one of a number of similar Buddhist nationalist organisations emerging throughout Asia. Its message is directed against minority groups, such as Myanmar’s Muslim population, and seeks to disenfranchise them further. It does so in the name of Buddhism, and demands that if its ideologies are not adhered to and actions are not undertaken, the religion itself is will be at risk. Naturally, in countries where Buddhism has an integral relationship with the country’s identity, the need to protect Buddhism enables mass social mobilisation for its defence.

Let us first look at the cases that indicated Ma Ba Tha was declining. The first blow to the organisation was the overwhelming National League for Democracy (NLD) victory in the elections of November 2015. The victory removed Ma Ba Tha from its close relationship with the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) that had allowed it to successfully lobby for the highly discriminatory laws to protect race and religion. In 2016, Ma Ba Tha took further hits. It was denounced first by the Chief Minister of Yangon, Phyo Min Thein in July. Following that, the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, the body that regulates the Sangha, disowned the organisation, further damaging its legitimacy.

Despite all this Ma Ba Tha remains active, particularly on social media. In response to Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak’s appearance at a pro-Rohingya rally in December, Ma Ba Tha released their own statement condemning it. The organisation’s spiritual leader, Ashin U Wirathu still actively posts on his Facebook page, particularly on developments in Rakhine State following the attacks by Rohingya on police stations in Maungdaw and Rathedaung townships in October as well as the subsequent Tatmadaw crackdown. These messages are widely shared and continue to shape hate speech, especially as the situation in Rakhine State continues to unfurl.

It is evident from recent events that Ma Ba Tha maintains an active and influential presence in Burmese society, despite what the NLD and civil society groups have stated. Though it seems, at the very least, Ma Ba Tha does not enjoy the same level of political access that it did under USDP rule.

So why do organisations such as Ma Ba Tha remain so influential, despite being dealt so many blows to their legitimacy? I suggest the world’s focus on the Rohingya people and issues in Rakhine State creates a perceived disenfranchisement of the Buddhist majority from their own plights. This ‘deep story,’ an idea raised by sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild to explain the shift towards Donald Trump in the USA, underlines an emotional story of unfairness and anxiety.

I believe a similar emotional story of perceived unfairness exists in Myanmar which allows the minorities such as the Rohingya to become an object at which to direct this emotion.

An example of this emotional narrative is the Tatmadaw’s brutal crackdown on the Rohingya and the responses revolving around it. Defenders of the crackdown discuss the history of Rakhine State and the cross-communal conflict that occurred during the Second World War between Rohingya and Rakhine communities in 1942. Thus, the sympathy from the global community towards contemporary issues facing Rohingya is deemed as unfair, as there has not been similar forms of condemnation for activities in the past.

The fact that this perceived injustice has gone largely unaddressed when issues of Rakhine state are brought up leads to the idea that the Burmese majority’s ideas and values are being rejected. This creates a narrative that forms the foundation for the emotional story. This emotional story, therefore can be readily tapped into by organisations such as Ma Ba Tha and used to further mobilise Burmese Buddhist society.

Ma Ba Tha remains prominent and will continue to be influential as long as the deep story, the emotional story of unfairness and anxiety, goes on. Like many organisations, it feeds into the narrative and utilises it. Ma Ba Tha offers solutions it claims can fix these wrongs and will only lose complete relevance when the story changes or Burmese society moves on.

Dinith Adikari is a recent graduate of a Bachelor of Asian Studies (Honours) from the Australian National University. His thesis was a historical analysis of how Theravada Buddhism was adapted by social movements to fit changing circumstances throughout Myanmar’s history. His research interests revolve around the intersections between religion, social movements and how they affect their surroundings.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss