Frank Palmos was just 21 years old when he began his career as a foreign correspondent in the relatively new Republic of Indonesia in March 1961. To reach the skill and experience level to succeed in his plan to open the first foreign newspaper bureau in Jakarta, Frank immersed himself in Indonesian society for two years, at universities, towns and villages. He also accepted assignments as a translator. What follows is the story of his first assignment as translator for a Colombo Plan team in 1961, the first of his 53 years in the region as correspondent and now historian.

Frank Palmos in 1961, age 21, at the Yayasan Siswa asrama, now the site of a mosque. Image: Frank Palmos

Jakarta was a busy, confusing, run down but exciting city in 1961. United Nations and Colombo Plan teams were helping the new Republic develop its infrastructure, while Russia and the USA invested heavily in projects in a Cold War competition for favours. Except for the ravages of a broken economy and 200 per cent inflation, life was a long string of thrilling assignments for a young journalist.

Although I had a room in a Kebayoran asrama (boarding house), I still stayed frequently with my friend from my first night in Indonesia, Nurwenda the Bank Negara clerk and his Bogor student friends, learning Bahasa Indonesia from the Imam in the Kampung Bali mosque in the crowded kampung of Tanah Abang. I had expected some religious propaganda in the mosque, but this Imam was rather special in that he concentrated on care for the local families, urging the mothers to give their children orange juice from Garut orchards, for everyone to scrub their hands and finger nails to maintain hygiene (I learned the word gosok: brush) and to be kind to neighbours by checking on the elderly to see if they needed help.

The Imam’s diction was clear, simple and grammatically correct. When I thanked him, saying he had inspired me to learn, he gave me just one piece of advice: “Avoid bad words or swearing. Then, you can never accidentally insult anyone.”

Listening to him helped me pronounce long names, which is why I was offered my first travel assignment as translator to the Colombo Plan team. The head UN engineer had heard me speaking what he thought was rapid Indonesian and offered me the position of fourth member of a team installing new, powerful Radio Republic Indonesia (RRI) transmitters that tripled the reach of RRI broadcasts from stations in Cirebon, Semarang, Surabaya, Malang-Jember, Madura and Lombok.

What the engineer had actually overheard was my repetition of the names of President Sukarno’s Second Working Cabinet in Guided Democracy! I loved repeating several names because of the rhythm and level of difficulty (for a foreigner), which gave him the mistaken impression I was already fluent. I was in luck, because I needed some extra paid work. Inflation had reduced my Fellowship stipend so much that I had been forced to earn extra by selling sweet pineapples on the Bogor road with my equally impoverished student friends.

My favourite names were Ipik Gandamana (Minister for Home Affairs), General Jatikusumo (Post and Telecommunications) and Martadinata (Navy). The toughest was Finance Minister, Notohamiprodjo. I dropped these names into conversations to anyone who would listen, even my becak driver Amin, who had no idea who they were, perhaps thinking they were old friends, not important government ministers.

Amin (standing) the becak driver, who became a reliable friend after Frank Palmos’ first drive from the airport in 1961. Image: Frank Palmos

UN team departs as birthday card arrives

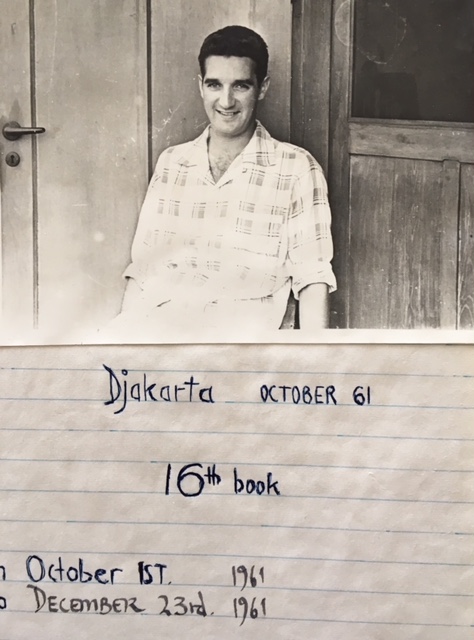

A UN-Colombo Plan Holden sedan picked me up from my asrama just as the mailman arrived with a large letter for me, so I took it along to read on the road. It was a large gilt-edged 21st birthday invitation from Les Rudd, a friend from my teenage years in Melbourne. The card was a bright purple, twice the size of an open passport, had crenellated gold edges, with a “white cloud” in the centre, where “Master Frank Palmos” was written in Italics. It was quite impressive, especially as the gold lettering glowed brightly in the sunshine. The word “flashy” sprang to mind.

The UN engineer leading the Colombo Plan convoy rode in the rear seat of a new Holden sedan, with driver and an engineer from Yogya in the front. I was supposed to ride with the driver, but the Yogya appointee felt more comfortable so I rode in the back with the engineer and his brief cases. Behind us was a long semi-trailer with driver and two radio mechanics in charge of six new transmitters in 2 x 2 meter steel cabinets.

The engineer was new here, having just arrived from working on the Aswan Dam in Egypt where he had suffered schedule delays lasting weeks, so he had set a very tight schedule of installing one new RRI transmitter every three days.

But he was the only one who thought we could do that. This was Indonesia, the roads were bad, so experienced travellers never set timetables, but let travel take care of itself. This was a town whose Gambir Railway Station frequently chalked signs that read: The 12.00 train to Yogya leaves at 15.00, with the 15.00 crossed out, replaced by 1630, then a chalked 18.00. I knew the driver and the Yogya engineer both expected to be away for weeks and secretly planned to visit relatives along the way.

The first hold-up came as we approached Cirebon, a port east of Jakarta. General Nasution, the Minister of National Defence, had ordered War Games be practiced on Java, so we lost almost a day waiting around Cirebon, where armed soldiers held us up at a roadblocks for hours, claiming our UN papers were insufficient, before letting us through. We arrived at our hotel late at night after all meals had finished.

I was up early and walked around the town while the others slept. Cirebon even in those days had a deserved reputation as a Tidy City, so the walk was enjoyable, and I had a noodle soup for breakfast at the Pasar (market) which opened at 6am. The UN engineer arose late, blaming mosquitoes for not sleeping well, ordered scrambled eggs on toast, which the hotel cook somehow messed up. He then complained the toast was not right, which held the rest of the team up for another half hour.

I wanted to tell the Yogya engineer what a wonderful town this was and say: “What a great breakfast and coffee I had at the Pasar!” But they were all a bit grumpy because of their messed-up breakfasts, so I kept quiet.

Around Tegal, further east, there was another roadblock. I got out of the back seat to show my passport and, by accident, was also holding the purple, gold-edged birthday card. The soldier saluted me, mistaking me for the team leader, and examined the 21st card as well as my passport. He was impressed and nodded his troops to let us through. The third roadblock was just before Semarang, where I showed both passport and birthday card, and we were waved through, again.

This was a magical card! From Tegal on the team gave me the job of showing the paperwork, and we got through without further delays. True, it was slow going during the military exercises, but we made it through several other roadblocks across East Java until we reached the outskirts of Surabaya.

The magical birthday card. Image: Frank Palmos

At the Wonokromo Bridge, the south gate to the port city, a young officer asked in perfect English: “Is this your team?” I said it was. He handed me back the passport and card. “You may go through. By the way, you’ve accidentally given me a birthday card. Are you from Melbourne?” He had seen the address. He had enjoyed studying there and felt “adopted” by an Australian family, and wished he could go back some day.

By the time we got to RRI Surabaya we were already three days behind schedule and the crew in the semi-trailer were a week behind. They had no birthday card, and no luck at roadblocks so called to say they would be two or three days late.

Our team had overnighted in the beautiful mountain resort of Tretes, where I met a “famous newspaper owner” in his weekend bungalow. Mr The Chung Shen owned the Djawa Pos, and was pleased to hear I was a journalist. He offered me a week’s work to help him improve the English section on his newspaper. The two Australian ladies on his staff were both ill.

So, while waiting for the transmitters to arrive, I worked on the paper’s English section.

Mr The and his wife owned an old classical colonial building in the heart of town. They arrived early on my first day and sat at desks in a room upstairs, his desk at the north end, her desk at the south. Mr The made advertisements for cinema clients while Mrs The used a wooden ruler to measure the length of reporters stories, for they were paid by the centimetre. All done in strict silence!

I was downstairs with the two reporters and an advertising man, cramped into a small room, sharing one telephone and one typewriter. My desk was tiny and its drawers full of make-up and hairpins and half-used lipsticks owned by Betty and Shirley, whom I never did meet. Their job was to translate the Antara Bulletins, which arrived morning and afternoon, and to do the weather.

There was no typing paper allowed, so the staff used the blank side of the Antara bulletins, which were printed on brownish, cheap paper that fell apart when wet.

Mr The told me to pay attention to the weather reports Shirley had written recently because there had been complaints. Weather forecasts were important to a big fishing fleet and to farmers bringing produce to market.

Shirley’s published weather published were as follows: “Surabaya weather. I hope it is a nice day today. It rained yesterday and I couldn’t do my shopping.”

Another report said: “Lets hope the rain stays away. It was so bad on Sunday we got sopping wet and had to cancel Ladies Day at Maspati House.”

Her forecast was: “We hope the weather improves! We’ve had enough rain!!!!”

“What’s sopping?” a reader asked next day.

Java’s Muslim Warrior Queen

This article explores the life and career of one of Java's great premodern leaders: the 16th-century queen of Jepara.

When I got back to the rundown, formerly grand Sarkies Majapahit Hotel, the UN engineer was holding a copy of the paper, frowning. “There’s an article in your bloody paper about the ‘RICH SPIES ISLANDS.’ Don’t they mean Spice?”

“Depends on the weather,” I replied.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss