From religious preachings, airport names and popular archaeology coverage in newspapers, the idea of finding the El Dorado of Asia is a continuing obsession. Finding relics attached to the fabled Suvarnabhumi, the so-called Golden Land that has appeared through centuries of oral tradition and religious narratives, never gets old for the archaeology and history enthusiasts of Southeast Asia. Suvarnabhumi, is a literary reference to a land that appeared in Sanskrit and Pali texts. The term often appears in Buddhist, Hindu, and Jaina traditions, with attempts by scholars to link its literal meaning, the golden peninsula, to other textual sources in Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Chinese. The location of Suvarnabhumi is highly disputed among scholars and governments. Some of the contending locations include: South India, Sri Lanka, Eastern Bengal, and various locations in Southeast Asia.

I wrote a research dissertation on Suvarnabhumi and have since developed an entirely different opinion on the subject. I was drawn to Suvarnabhumi. Identifying the so-called land of wealth and mystery, which as far back as Ashoka (c. 268 BCE) attracted missionaries and merchants from India, China, and Europe, seemed like a task for the secret Indiana Jones hidden in every archaeologist of the pop-culture generation. It is still the dream of many archaeologists to find a lost city or civilisation, much to the dismay of many conservationists trying to prevent invasive archaeology in heritage hotbeds like Cambodia, Egypt, and South America. I have seen books written by both amateur and academic writers reiterating the same context: that Southeast Asia is a land of trade, it is the stop for traders, it is very wealthy, the list goes on and on.

While we have to appreciate the profound work of scholars like O.W. Wolters, H.G. Wales, Georges Coédes, and the impeccable work on Chinese texts by Paul Wheatley, historians have gotten used to treating Suvarnabhumi or its synonyms in other languages as a historical-geographical fact. I argue, instead, that Suvarnabhumi is a literary device. We need to work together as archaeologists, linguists, local and international, art historians, historians and heritage scholars to get rid of the idea of Suvarnabhumi as a physical location. I am not saying we should stop studying Suvarnabhumi, but perhaps it is time we stop treating it as a piece of empirical source material.

The Origins of Suvarnabhumi

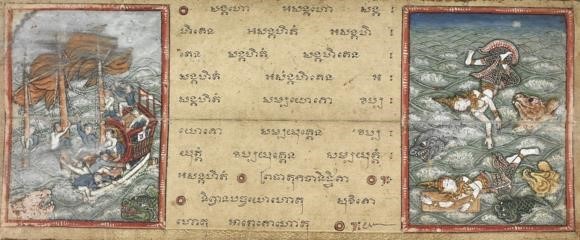

A 19th-century text depicting Jataka or Buddha previous lives stories. Mahajanaka Jataka refers to Suvarnabhumi as an intended destination before a shipwreck. The story is highly popularised in Thai and Burmese Buddhist communities. Photo Credit: British Library, Or.14559, f. 5.

The term Suvarnabhumi appears in three contexts in its original linguistic form, either in the Pali or Sanskrit languages:

1. As a location in mythical or religious stories;

2. As a reference in short and vague accounts of trade;

3. As a comparative political narrative for a local audience with no access to the actual location of Suvarnabhumi.

Mentions of the Golden Land appear in South Asian, Chinese, and the often-cited Greek and Roman sources. Analysis of Chinese and Greco-Roman sources echoes a borrowing and matching method from studies on Pali and Sanskrit sources; for example, Chin-Lin uses the Chinese character “golden city” and subsequently equates it to the golden land: Suvarnabhumi. The same applies to the term Aurea Regio in medieval sources allegedly copied from Classical sources, as well as to the ongoing quest to take Ptolemy’s map as an actual exploration account. I will come back to this point on Ptolemy later.

In light of recent attempts to de-colonise and review Eurocentric narratives, Suvarnabhumi is the colossus of colonial historiography. It exoticises and orientalises the landscape into shrouds of myths and legends, but more importantly, it subjects Southeast Asian historical narratives to the significance of non-Southeast Asian actors. According to this view, the historicity of Southeast Asia began with the diffusion of trade, technology, and statecraft from an external agency. Chronology also becomes a big debate every time a discussion on early ‘states’ in Southeast Asia emerges. Some scholars dance around this gaping hole by ignoring the issue altogether and avoid contextualising their studies into a broader landscape. Archaeology and history often struggle to break away from national or site-specific studies within modern national boundaries. The baggage that accompanies Suvarnabhumi as a historical concept is its very absence of historicity, the lack of a cultural context in which it is to be placed. In other words, the problem is the claim that cultural complexities in Southeast Asia does not exist without the roles of external agencies and identities.

Southeast Asian historical identity continues to grapple with its colonial legacy and decolonisation narratives. In many countries, it has been a constant challenge to pull away from the idea that mainstream religion from South and East Asia triggered state development in Southeast Asia. Few scholars have dared venture into the realm of mentioning local technological development when it comes to discussing bricks and masonry in the archaeological record. This deeply entrenched theory of external agency culminates from a century of treating Southeast Asian history as an extended part of South Asian and East Asian stories. We cannot deny the Eurocentric origins of history as a subject. The Victorian fascination with understanding the world under empire continues to permeate through orientalist and antiquarian approaches to regional history. Southeast Asian material culture becomes an orphan, adopted by the identities of its better-understood South Asian and East Asian parents. Polities in Southeast Asia could not be conceptualised as existing without being treated as Suvarnabhumi and therefore in terms of trade with its parental cultures.

Follow the conversation on Facebook or Twitter!

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss