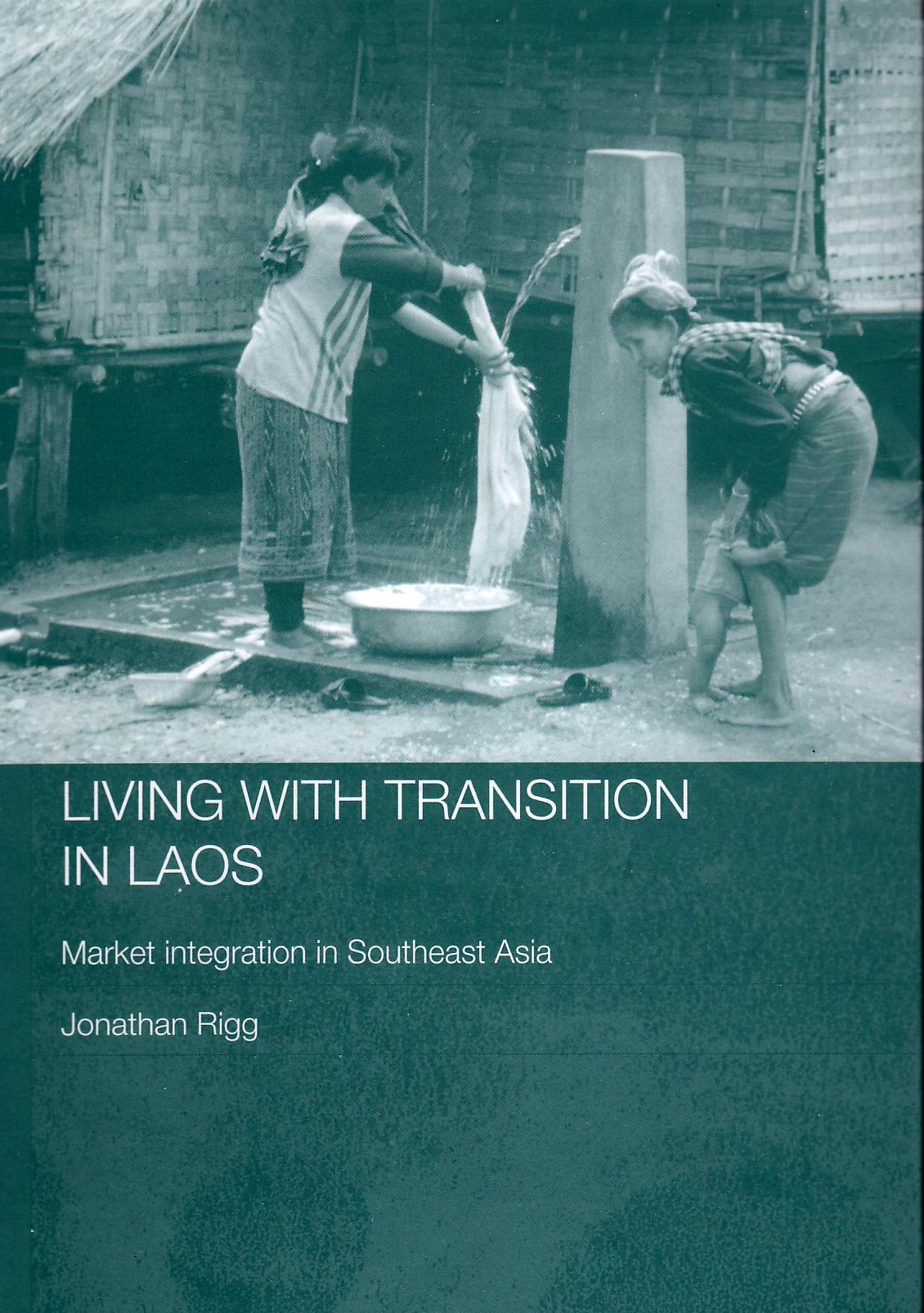

I have just finished reading Jonathan Rigg’s Living with Transition in Laos.

This is an important and accessible account that has implications for policy and academic analysis that extend well beyond Laos. Rigg presents a balanced account of the impacts of development on the rural poor in Laos. He documents both “policy induced” and “market induced” forms of “new poverty” in Laos. Particular attention is given to the government (and aid-agency supported) policies of relocating upland people’s to lowland “focal” settlements. Unlike some commentators, Rigg is no romantic when it comes to upland livelihoods but he paints a clear picture of the impoverishing impacts of some cases of “sedentarisation.” He also documents the impact of market expansion on forest products. In Southeast Asia there is often a tendency to overstate the dependency of rural people on forest products (a process I have referred to as “arborealisation“) but in Laos there is a convincing case that forest products play a crucial role in supporting often marginal rural livelihoods. Forest product depletion is likely to run well ahead of the benefits of rural modernisation meaning an exceedingly difficult period of transition for some.

Underlying Rigg’s account is the argument (that he has developed in a number of previous publications including the invaluable Southeast Asia. The Human Landscape of Modernisation and Development) that it is a mistake to equate rural livelihoods with agricultural livelihoods. Even in relatively under-developed Laos, what Rigg refers to as pluriactivity is becoming increasingly common. This, I think, is the most important message from this book. Rural Development strategies (and post-development appeals to self-sufficiency) will fail unless they recognise the rural can no longer be simply equated with the agricultural. And, importantly, agricultural livelihoods are increasingly underpinned by diverse sources of off-farm income. As Eric Wolf wrote long ago the so-called “closed corporate community” “can maintain its integrity only if it can sponsor the emigration and urbanization or proletarianization of its sons.” Proletarianization may have negative connotations for many of the critics of modernity in the region, but for the rural poor (and their sons and daughters) it often represents a much sought after opportunity for livelihood improvement and socio-cultural diversity. As processes of economic transition unfold in Laos these opportunities, albeit unevenly distributed, appear to be proliferating. This is the cautiously optimistic conclusion of Rigg’s very valuable account:

…the danger is to see the poor in Laos not only as victims of development, but as accidents of history. It is at this point that the here-and-now comes into play, and it is here that the value of building an understanding of local livelihoods becomes clearest. There is no doubt that households in Laos have been uprooted and resettled, and established livelihoods have been compromised in the process. The discussion [in this book] shows, however, the degree to which people willingly contribute to these processes and, moreover, sometimes act as prime movers in the reorientation of their lives. The political economy of liberalisation and reform may have created real difficulties for some groups and individuals. It has also, though, provided the same groups and individuals with new tools and opportunities with which to succeed.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss