1MDB shows that an already fragile rule of law is being stretched to the limits, writes James Giggacher.

Malaysia’s rule of law may have reigned supreme in this week’s case of the Budgie Nine – saving the Southeast Asian state from gross national insult at the hands of some silly young Australians.

Too bad the same thing can’t be said about another national disgrace, the 1MDB financial scandal.

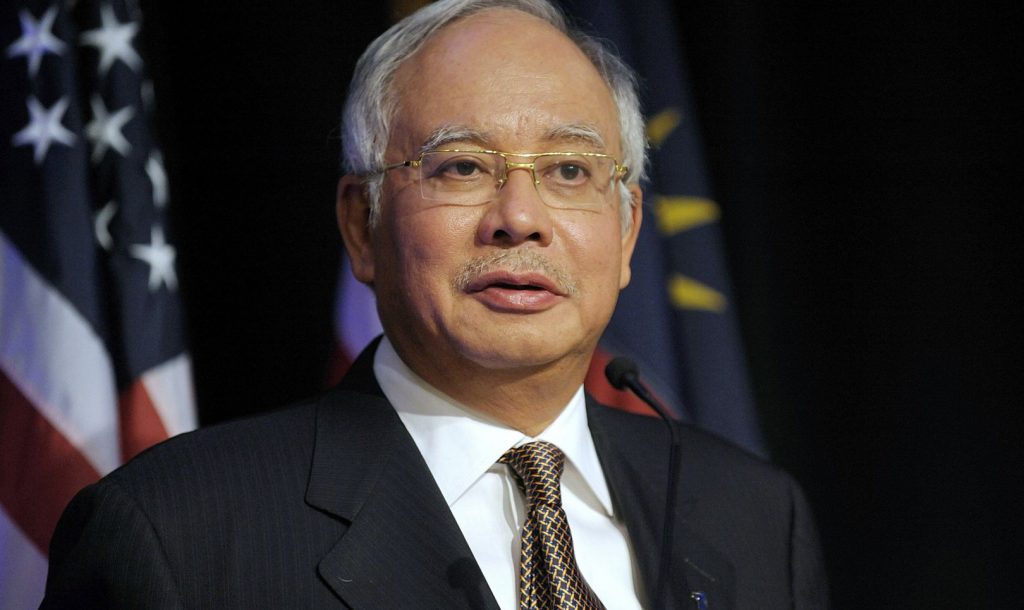

In the face of investigations into the country’s failing sovereign wealth fund, and Prime Minister Najib Razak’s alleged links to millions of missing dollars, the rule of law has in fact gone missing in action.

This was certainly the case when Najib sacked attorney general, Abdul Gani Patail, who planned to bring charges relating to 1MDB against the PM in July 2015.

The plan was leaked, and Abdul Ghani stepped down, officially for ‘health reasons’. Perhaps he’d heard about what happened to former Mongolian model and Najib’s inner circle mainstay, Altantuya Shaarribuu.

At the same time, Najib removed his deputy and one of his most vocal critics — Muhyiddin Yassin.

The former AG’s replacement, Mohamed Apandi Ali, almost immediately cleared his embattled PM of any wrongdoing.

Apandi said that the royal family of Saudi Arabia had gifted Najib $US 681 million, of which $US 600 million had been returned. He also said no criminal offence had been committed. However, several countries, including the US, Switzerland, Singapore and the Seychelles, are still investigating the case.

Reports on the scandal by Malaysia’s central bank and anti-corruption commission have also been dismissed by Apandi; according to him the PM has no case to answer.

And in June, Najib filed court documents that denied graf, misuse of power, and interference in 1MDB investigations in response to a lawsuit brought by former PM and mentor, and now key adversary, Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

Meanwhile, the almost 700 million dollar question of how 2.6 billion ringgit managed to find its way into Najib’s personal bank accounts has yet to be satisfactorily answered.

So much for due process, democratic safeguards, transparency, and holding those in power to account. But can we expect anything better from a Malaysia still under the sway of long-ruling coalition Barisan Nasional (BN) and its leading party, Najib’s UMNO?

The dismantling of and disdain for judicial and state institutions is not a recent phenomenon. As Jayson Browder notes, BN has long had a poor record of abiding by the rule of law.

It has consistently leveraged several national laws – including The Peaceful Assembly Act of 2012, the Sedition Act of 1948, and the Printing Presses and Publications Act of 1948 – to curtail freedoms, assembly, political expression as well as intimate activists, opponents, civil society and the media, and ensure its power.

These tactics guarantee the ruling coalition’s stranglehold over Malaysia’s political system “in direct violation of Article 10 of the Federal Constitution in Malaysia.” Article 10 is meant to guarantee Malaysian citizens the right to freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and freedom of association.

An embattled Najib has only sharpened the teeth of a legal system already heavily stacked in his party’s favour. In August he brought in an unprecedented law that allows him to designate ‘security areas’ and deploy forces to search people, places and vehicles without a warrant.

Draconian would be an understatement.

Laurent Meillan, from the UN Human Rights Office for Southeast Asia, said that they were “gravely concerned” about human rights violations as a consequence of the act. The act could further restrict already highly limited rights of free speech and free assembly.

And in March this year, the independent news site The Malaysian Insider, went offline. Owners cited poor financial returns and high costs. The then editor, Jahabar Sadiq, said it was because the threat of being charged with sedition that could lead to jail time had become all too real.

The decision to pull the plug came almost three weeks after Malaysia’s Internet regulator — the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission – issued a gag order on the site because of a report alleging the country’s anti-corruption commission had sufficient evidence to bring criminal charges against Najib in the 1MDB case – even though he had already been cleared by Apandi.

The lesson? Smuggling budgies and smearing the flag is a clear no-no. Smuggling billions and smearing the nation’s sovereign wealth fund is a-ok.

It all goes to show that in Malaysia there is the rule of law – but most of the time there’s the law that lets BN rule.

James Giggacher is an associate lecturer in the ANU Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs and editor of New Mandala.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss