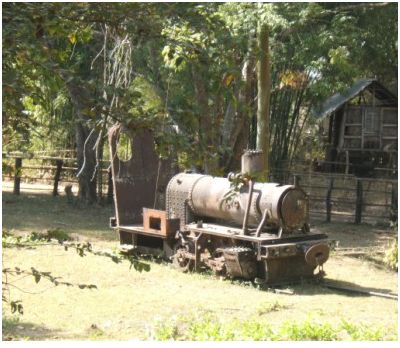

Just as the train has always been a symbol of progress, Laos’s unusual distinction among its neighbours of not having a railway system has long demonstrated its lack of development. A rusted locomotive in the far south, the last vestige of early-20th century French efforts to bypass the Khon Phapeng falls on the Mekong River, testifies to unrealised colonial dreams, lying in moribund contrast to the dynamic train-building that took place next door in Siam. Despite being celebrated in Laos itself, the recent opening of a 3.5km stretch of track from outside Vientiane to the Friendship Bridge (which connects the city to Nong Khai in Thailand) has only reinforced Laos’s historic lack of transport infrastructure.

So, as well as promising obvious economic benefits, last week’s announcement that China has agreed to fund a new railway in Laos has great symbolic importance. A century after the first French plans to extend its Indochinese rail network into Laos – ideas that bubbled along until the Second World War – it seems that, thanks to the region’s newest power, Laos will finally be connected to it neighbours by train. The planned train will link Vientiane to China in the north and, via Khammouan Province, Vietnam to the east. This is supposed to happen within five years – an ambitious target, but one that demonstrates the can-do mentality of Chinese investment.

When the French were investigating railways in the first half of the 20th century, it was to link Laos to its greater Indochinese possessions in what became Vietnam. Just as colonialism shaped earlier railway-building plans, now it is the defining narrative of regional integration that rules. The expressed goal is to link Laos to ASEAN and China, by connecting to the Singapore-Kunming railway and, in turn, the greater Chinese network.

But as the parallel with French colonialism suggests, the planned train is also symbolic of the expanding role of China in Laos and Lao development, and questions this raises for national sovereignty. As I wrote before the SEA Games in December last year, the paradox of foreign-funded development is hardly new to Laos. The nation – like the pre-colonial Lao kingdoms and colonial state that preceded independent Laos – has always grown out of engagement with foreign powers. Lao leaders are comfortable with what may seem contradictory to some outsiders, proud of rather than embarrassed by foreign assistance. As long as the Party-State can project itself as conductor of foreign forces, as it did so effectively in the SEA Games, it (with the economy) will prosper with the help of the Chinese.

The question, I would suggest, is how far this development strategy can go. The SEA Games were successful because, in spite of their massive dependence on foreign and particularly Chinese capital, they provided an occasion for celebrating national success, unity and future potential. The controversy over the ‘Chinatown’ development near That Luang – which was condemned by some as treasonous (khai sat, lit. sell nation) and continues to bubble along – did not untimately overshadow the games, perhaps because it affected relatively few people compared to the masses that embraced the festive nationalism of the event. However, opposition to the development did demonstrate public sensitivity to Chinese investment, to the extent that the proposal sparked quite unprecedented popular opposition among those that stood to lose through such investment.

Like the SEA Games and China’s purchase of the Sepon mine in Savannakhet, the Chinese railway deal dramatically demonstrates the latest development paradigm of the post-socialist state in Laos: increasing regional integration through regional – and especially Chinese – investment. But as history tells us, no such paradigm is timeless. The French were once embraced for their trains too.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss