21 April—Hari Kartini, or Kartini Day—is a day of civic celebration in Indonesia when the nation commemorates the birth of a young Javanese woman who lived and wrote at a critical time of change in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). This commemorative day has come to be focused, in often contradictory ways, on the place of women in modern Indonesia. The day is marked with civic ceremonies, especially in schools and government institutions; and media reflections on the state of women’s social participation, challenges and achievements.

We know Kartini primarily through her correspondence, which has been published in a broad range of selections and translations. Only recently (2014), though, was a full edition of the letters available In English, through decades of effort by Monash University scholar Joost Coté. This literary corpus, and perhaps the poignancy of her short life, have become fodder for varied and ever-changing interpretations of the figure “Kartini”. Especially since independence, this cultural icon has been represented in a range of ways that suit the power struggles of the times.

Kartini, born in 1879, was a young high-born woman, the daughter of a priyayi (Javanese noble) colonial official. In that pre-nationalist era, forward-looking men of his class began to learn—and ensure their children learned—Dutch, so they could seek advancement and achieve influence in the NEI civil service. She attended the local primary school to be educated alongside Dutch and Eurasian children. In one of the many ironies of her story, at age 12 she was withdrawn from school to begin the customary period of seclusion (pingitan) prior to an arranged marriage (a life course appropriate to a girl of her high social standing).

Despite Kartini’s withdrawing from formal education, this scholarly and gifted young woman used her time within the walled gardens of her home to read widely in Dutch: novels, magazines, newspapers, as well as the more customary pursuit of handicrafts.

Her father’s official position brought Dutch visitors to the home. In the years 1899 to 1903 she had several long and intense correspondences, principally with one of these visitors, Nyonya Abendanon, the feminist-leaning wife of the colonial official J.H. Abendanon; and also a pen pal, a Dutch feminist named Stella Zeerhandelaar. Through her reading and correspondence, Kartini and her sisters were exposed to the currents of late 19th and early 20th century European thought, and were caught up in the radical social transformations of the age.

‘LIPSTICK FOR MOTHER’, A 1981 PAINTING BY DEDE ERI SUPRIA FEATURING KARTINI’S IMAGE

We can get to know Kartini essentially as a literary figure, her ”epistolary self” that she presented in her correspondence. She is a gifted and compelling writer, who cares about the situation of women and their rights in marriage and the poverty of her fellow colonial subjects. As the daughter of a minor wife in a polygamous household, she was critical of the custom of polygamy as she contemplated her own probable fate. In another irony, she agreed to her father’s choice of spouse, the widowed Bupati (Regent) of Rembang. Kartini replaced his deceased principal wife but still found herself in a polygynous household with several minor wives. She died soon after giving birth to a son in 1904.

As evidenced in her letters, Kartini was passionate about education and secured her husband’s approval to establish a small school in his home. She expressed a strong desire for further education, and through her pen pal’s efforts, was offered the possibility of study in Holland. In another twist, the man who dissuaded her from this plan, the colonial official J.H Abendanon, published an edited selection of her letters in 1911. His selection emphasised her passion for education, which fitted his own policy ideals for the NEI. The title, as rendered in the later English translation, From Darkness into Light, is paraphrased from one of the letters, and expresses a modernist trope of progress.

While Kartini wittily mocked the pretensions of some NEI officials in her letters, she lived in an era prior to the nationalist ”awakening” in the early 20th century. She expressed views about improving the governance of the NEI, not dissolving it, in part to be achieved through higher participation of ”native” officials and—echoing the sentiments of critics arguing for reform, and the so-called Ethical Policy—attention to native welfare.

But Kartini’s commitment to social justice through education and her articulate championing of education for women struck a chord with the emerging nationalist movement. The song that is performed on Hari Kartini, “Ibu Kita Kartini” (Our Mother Kartini) was written in 1931 by Wage Rudolf Supratman, who also penned the Indonesian national anthem, “Indonesia Raya”. Following her death, her sisters founded schools that developed into the Kartini school movement, providing education for “native” children. Education was a key theme of the struggle for independence.

The resonance of her writing with nationalist causes culminated in founding President Sukarno naming her a national hero (Pahlawan Nasional) in 1964, along with two other heroines of the armed struggle, Cut Nya Dien and Ceut Meutia, both armed fighters from Aceh. However, only Kartini—who, it is often noted, struggled with the pen and not the sword—has an eponymous day.

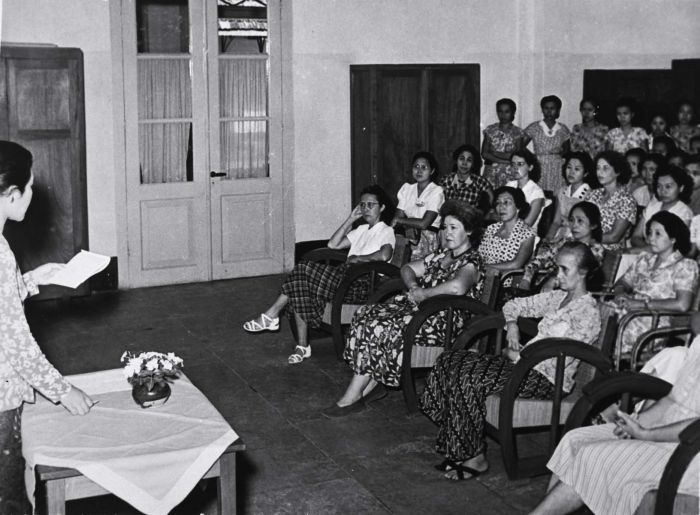

COMMEMORATING KARTINI DAY IN 1953 (PHOTO: TROPENMUSEUM)

For Suharto’s New Order regime, gender ideology was critical to the exercise of authoritarian power. State support for the exercise of male authority in the family legitimated the figure of Father-President who presided over the nation. “Kartini” was called into service in this ideological framing of the nation. She was remembered as a mother and a model for citizen mothers’ dutiful contributions to the nation.

The corporatist women’s organisations (like Dharma Wanita and the PKK/Family Welfare Movement) had responsibilities in the implementation of state programs like family planning and child health, as well as inculcating the state ideology and the primacy of women’s citizenship in wifely duties and mothering.

These organisations took a key role in the civic ceremonies of Hari Kartini, promoting the adoption of a costume of batik wrapped skirt and long-sleeved blouse (kain kebaya), the garb that Kartini is wearing in the significant photographic record of her life. This ”offical” dress was accompanied by high-heeled shoes and a false bun (konde) affixed near the nape of the neck.

The remembered ”Kartini” was a wife and mother who was responsible in the exercise of her duties and who tragically died in childbirth. Apart from promoting costumed look-alike competitions, Hari Kartini celebrated patriotic womanhood as wifeliness and motherhood in “healthy baby” competitions and cooking demonstrations. In Hari Kartini speeches of the New Order era, her memory was also invoked in support of the state-sponsored family planning program. However, the government also invoked her aspirations for education and social recognition of women to assert that they had achieved these goals for women.

TWO IMAGES OF KARTINI ON THE RP10,000 NOTE IN THE 1980S

But ”Kartini” has always provided a flash point for contestations around gender roles. In the late New Order, from the mid-1990s, issues that galvanised opposition to the regime included reports of the fate of Indonesian women migrants working as domestic servants in the Middle East and East Asia, and the poor treatment of women working in Indonesian world market factories.

In 1995, women’s rights activists chose Hari Kartini to stage a day-long protest beginning with a ”pilgrimage” to her grave near Rembang, where they gave speeches and (in the manner of protests of the day) staged a ”happening”, a street performance of men enslaving women. They moved on to the Kartini museum at the site of her former home: because the official ceremony was being conducted inside, they occupied the yard for their protest. They also demanded the dissolution of the official women’s ministry on the grounds it did nothing to promote women’s real interests.

ASEAN and women: empower movements, not just individuals

Programs to increase women’s market competitiveness aren't a substitute for collective action for gender equality.

In contemporary Indonesia, primary schools remain an important site for celebration of Hari Kartini, as an aspect of civic education. Whereas under the New Order, the emphasis was on dressing up in kain kebaya, today the prescribed dress is pakaian adat, or customary local costume, perhaps reflecting the spirit of decentralisation and public criticism of Javanese domination of the nation. So today’s celebrations go back to the roots of her nomination as a pahlawan nasional, commemorating the nation as well as focusing on women’s social position.

What does Kartini mean to the today’s youth, the millennial generation referred to as zaman now?

Over the decades, “Kartini” has become a free-floating signifier that is used for commercial, political, and cultural ends. This year, for example, a smart Jakarta hotel is offering 25% off cocktails for women on 21 April and suggesting they post at #KartiniNowadays. Garuda Indonesia adverts have targeted female passengers as ”new Kartinis”, represented as smart young women in western dress and with stylish short hairstyles. There are new cultural products relating to Kartini, such as a recent feature film and the several new books that have just hit the shelves in time for Hari Kartini.

GARUDA INDONESIA “KARTINI FLIGHT” PUBLICITY SHOT, 2017

In late 2017 I interviewed young people in three Indonesian cities (Kupang, Makassar and Surabaya) asking about their engagement with Kartini. Overall, the young people did not did not read Kartini’s work, or any of the many books about her. None had seen the 2017 film. They reported that their knowledge came from the civic ceremonies and speeches in primary school.

KARTINI DAY PROMOTION FROM AN ITALIAN RESTAURANT CHAIN IN JAKARTA

Nevertheless, Kartini remains a cultural icon for them. Young men and women (approvingly) expressed her historical significance as relating to ”emansipasi” of women and women’s education. Picking up on the shift from Kartini day celebratory kain kebaya-wearing to the emphasis on wearing locally-specific traditional garb, in some of the conversations the young people questioned why there was not also celebration of heroic women from outside Java.

In the period around 21 April, when Kartini is ”booming”, the zaman now generation post commemorative pictures of themselves on social media such as Instagram, using tags such as #Kartini or #HariKartini. The ”grammar” of these postings involves wearing kain kebaya or other ”traditional costume”, and posing with friends and, frequently, their mothers. I was told of a most engaging commemoration of ”Kartini” as a trope signifying emancipation: a group of young women nature lovers climbed a mountain on Hari Kartini and donned kebaya at the summit before taking photographs. The invocation of Kartini signified that they were the first women to achieve this, and also that women can do anything (or everything!)

2016: YOUNG WOMEN CELEBRATE KARTINI DAY ON MOUNT MERBABU, CENTRAL JAVA

The shifting representations of Kartini as a touchstone for women’s rights issues has not escaped the current trend to increased pubic piety and concern to express civic values in Islamic terms. The 2017 Women Ulama Congress (KUPI) was held on 25 April—in the Kartini ”season”—invoking the idea that late April is the time of year for ”taking stock” of women in Indonesia and addressing agendas for change. The congress materials referred to Kartini and her Islamic education and values in developing their recovered history of women’s religious authority. A more thoroughgoing ”greening” of Kartini has come from some religious scholars who have mounted the revisionist argument that her critique of women’s position and her calls for change were rooted in the Islamic texts she studied, not in western literature and political theory.

Ultimatley, Kartini was a young woman of her time and place, in an ambivalent place between 19th century modernist ideals and her deep love of Javanese cultural traditions. Kartini—or rather the day that celebrates her life—occupies a unique position in Indonesian political and cultural life where each year the nation celebrates womanhood, albeit in shifting guises, but also pauses to reflect on what the nation is doing, and should do, for female citizens.

• • • • • • • •

This post is adapted from a chapter of a forthcoming volume on Kartini edited by Paul Bijl and Grace Schirripa.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss