Many analyses of Myanmar’s civil war and stagnant peace process follow a common pattern in the study of war and peace: they focus on warring elites and their strategic decisions. Despite the importance of elite politics, we also need a greater appreciation of the everyday lives of non-elite members and supporters of Myanmar’s ethnic armed organisations (EAOs). Understanding their perspectives, aspirations and lifeworlds is of great importance because they form the social foundation of decades-long armed resistance against the ethnocratic state of Myanmar. EAO leaders rely on their support. This makes them an important part of revolutionary politics in Myanmar.

In a recent article published in International Political Sociology, I analyse revolutionary music and the social practice of karaoke in Kachin State to consider the everyday lives of rebel grassroots and the social fabric of rebellion in northern Myanmar. Similar to other regions in East and Southeast Asia, karaoke is a favourite pastime amongst young people in war-torn Kachin communities. The Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO)—one of Myanmar’s oldest and strongest EAOs—has tapped into the popularity of karaoke for mobilising against the state and propagating its own ethno-nationalist ideology surrounding the creation of a homeland for the oppressed Kachin minority.

In recent years, the KIO has produced professional karaoke-style music videos, which feature scrolling subtitles that help viewers to sing along. Some of them are remakes of decades-old revolutionary songs that have been used to mobilise Kachin communities since the 1960s. One refurbished classic from the 1970s is called “Shanglawt Sumtsaw Ga Leh,” which means “The Love for the Revolution.” Its lyrics are about courageous rebel soldiers calling on beautiful young women to marry them after graduating from school.

While the modern remake features nationalist and revolutionary symbols—including dashing uniforms and minority costumes—the video also reminds of modern pop/rock clips produced by boybands elsewhere. Handsome young men with sunglasses and blue jeans are flirting with pretty girls wearing make-up and fashionable clothes.

The Kachin rebellion also produces new songs, many of which reflect a changing depiction of social norms, including traditional gender roles. A music video that can be found on a recent KIO recruitment DVD, for instance, portrays a young Kachin couple. He wakes up in a large bed next to an Apple laptop and starts into his day in a modern urban environment. She awakes in camouflage in a frontline position, braving the hardships of war as a frontline soldier of the Kachin rebellion.

Many songs and music videos depict idyllic modernity and revolutionary heroism, aspirations that resonate with local Kachin youth, many of whom live in depressed contexts characterised by violence and social problems, including widespread disillusionment about the dire state of the local economy. Analysing the audio-visual aesthetics of revolutionary music videos enables for a better understanding of this emotional dimension of rebellion, that is, its appeal to affect rather than reason.

That said, local communities are not only passive consumers of rebel propaganda that converts young people into gun-toting rebel soldiers. Merging visual method with ethnography reveals how many young Kachin actively and creatively engage with revolutionary music by performing rebellion in karaoke bars and producing their own music in independent studios. This provides a rare window into the hidden social fabric of political violence, including the formation of revolutionary subjectivities and revolutionary discourse at large.

Analysing the practice of karaoke—understood as a scripted simulation of rebellion – in fact demonstrates the performative aspect of identity formation. Playful performances of rebellion can be a powerful vehicle for youth in Kachin State to escape everyday marginality and to exercise agency against state domination. At the same time, reiterated performance of Kachin nationalist discourse forms revolutionary subjectivities within a new set of disciplinary constraints.

This discourse itself however is also coproduced at different levels of the Kachin society. Independently produced music videos show how young Kachin musicians actively impact on this revolutionary discourse. By singing against harmful mega-development projects or the local narcotics crisis, Kachin musicians give voice to the concerns of local communities and mobilise social resistance.

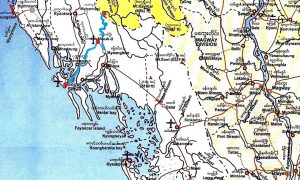

The rock band Blast produced one of the most famous independent Kachin songs in 2007, at the time of mounting resistance against the Chinese hydropower dam project at the Myitsone confluence of the Mali and N’mai Rivers. Their song Mali Hka [Mali River] encapsulated a wide-spread fear that the dam poses an existential threat to the Kachin society and nation. In merging environmentalism with Kachin revolutionary nationalism, it functioned as a major rallying cry against “foreign” “self-interests” that threaten the Kachin “life-line,” and urges resistance: “patriotic people, let us protect our precious treasure with all our might!”

Assessing the Rohingya crisis

With the expulsion of the Rohingya largely a fait accompli, the world must face up to engaging with a very different Myanmar.

Specifically, my enquiry into revolutionary music and karaoke in Kachin State urges: a) a relational analysis of rebel politics in order to appreciate the social foundations of armed resistance and highlight the reciprocal and dispersed nature of power that emerges from the interdependencies between revolutionary grassroots and elites; and b) the development of critical methods and the use of alternative sources of data that can capture the hidden social fabric within which conflict and violence takes place beyond our usual prism of elite politics.

“Performing Rebellion: Karaoke as a Lens into Political Violence” can be accessed free until 1 September 2018 by courtesy of International Political Sociology and Oxford University Press.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss