(Image: ┬й Catherine Ingram 2012)

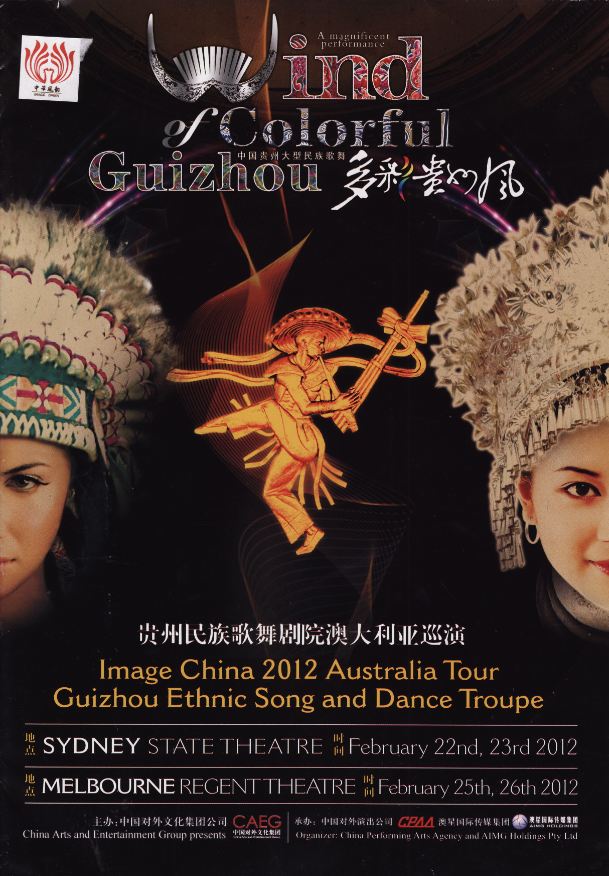

February and March of this year saw a large-scale performance from China called Wind of Colourful Guizhou (in Chinese, хдЪх╜йш┤╡х╖ЮщгО) touring through major cities in Australia and New Zealand. To my knowledge, this was the first time that the cultural heritage of this southwestern Chinese province was presented on such a scale for audiences in Australasia. But especially, it was the first time that ‘big song’–the important Kam (in Chinese, Dong ф╛Ч) minority song genre inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009–was publicly performed in these regions.

In China, the promotion and format used for staged performances of cultural heritage generally follow a typical pattern, and readers familiar with that model might have easily predicted the content of Wind of Colourful Guizhou’s publicity as well as of the event itself. The promotional details released by one of the organizing companies (interestingly, these companies included Australian property developers aiming for the Chinese market, besides Australian Chinese broadcasters and Chinese state-sponsored arts ventures) described Wind of Colourful Guizhou as ‘designed to elaborate Guizhou’s rich cultural heritages such as folk songs, artistic writing, symbolised dances and myths stories. It is dedicated to Guizhou’s ethnic minorities and pay tribute [sic] to Guizhou’s tourism.’

First premiered in 2005 and apparently since performed 1500 times in eleven countries worldwide, Wind of Colourful Guizhou claimed to showcase the singing, dancing, beliefs and other cultural activities of five of the seventeen officially identified minority groups that have lived in Guizhou for centuries. Collectively, these minorities comprise more than a third of the province’s population. Besides the programme for the performance including song and, particularly, mime-dance items attributed to different Miao groups (groups sometimes known in the West as Hmong) and to the Yi and the Yao, it also listed three items from two Tai-Kadai groups: the Gelao and the Kam.

While Wind of Colourful Guizhou was billed as emphasising the cultural heritage of Guizhou’s minorities, the performance I attended at Melbourne’s Regent Theatre in late February 2012 instead relied most heavily on an over-amplified electronically created soundtrack. In this, it resembled the earlier staged version of the show I had seen in Guizhou’s capital of Guiyang in 2005, and presumably also the hundreds of other versions of the performance given since. The electronic soundtrack mainly featured synthesized Western and Han Chinese orchestras, occasionally mixed with ambient sounds from nature and recorded samples of drumming or of singers performing songs in a language other than Chinese. It formed a musical accompaniment for all the mime-dance performances and, in the case of several items, a karaoke backing for vocalists. Amongst these karaoke performances, only a small part of one song used a language other than Chinese.

The 50-odd performers in the show were members of the Guizhou Ethnic Song and Dance Troupe, the province’s peak professional performance troupe. The ease with which ‘Miao’ dancers reappeared performing Yi culture, and singers in full Miao attire reappeared singing Kam song, served as a reminder that the performers themselves weren’t necessarily performing their own cultural traditions. But since the link between most of the items and Guizhou’s minority cultures seemed tenuous at best, the highly synchronized dancing and the occasional vocal items could still be executed without a hitch.

The performance of Kam ‘big song’ stood out amongst the other items. It was the only performance given without an accompanying electronic backing, and also the only vocal item performed live that was entirely in a minority language, rather than in Mandarin. Yet of the eight ‘Kam girls’ that the MC introduced to perform big song, only two spoke any Kam. One of these two young women had the important task of singing the solo introductions to each section of the song. That singer, Wan-may (pictured above, third from left), was born in the well-known big song singing region known as Sheeam (in Chinese, Sanlong ф╕Йщ╛Щ). She led the other women in a performance which I think most of the Kam villagers in Sheeam that I have worked amongst and sung with since 2004 would have commended.

Admittedly, the women’s performance of ‘Song of Cicada’ [sic] did not give listeners the experience of an authentic big song, as it actually combined two verses each from two quite different big songs (as is increasingly common in staged big song performances). In the lack of logic in the song lyrics, and the fact that neither of the two original songs contained the meaningful lyrics and complex rhyming patterns that Kam singers traditionally associate with the most important songs, audiences were further short-changed. But thanks largely to the excellent vocal abilities of the two Kam women in the group, the distinctive feature of all big songs–the two simultaneous vocal lines–rang out clearly. The women’s performance was immediately followed by a segment of mime and dancing to an electronic soundtrack featuring a Kam ‘wine song’, after which the largely Chinese-background audience applauded as loudly as they had for all the other items.

Readers–especially those who have seen firsthand the rich and impressive cultural traditions of Guizhou’s minorities–might rightly be bemused as to why local minority experts had little role in Wind of Colourful Guizhou, and why the items did not more closely resemble village performances. Despite the well-founded concerns surrounding the international identification of certain traditions such as Kam big song as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage, it is possible that in this instance such international recognition played a useful role. Granted, the rendition of big song that featured in Wind of Colourful Guizhou would only ever appear in a Kam village in the context of a staged performance. Nevertheless, earlier this year Australian and New Zealand audiences had a brief opportunity to appreciate a performance of local culture that I think most expert Kam singers would gladly have called their own.

Related links

http://www.newmandala.org/2009/10/24/chinas-60th-anniversary-from-the-margins/

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Wind-of-Colourful-Guizhou-Australia-Tour-2012/149826031796616?v=info

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss