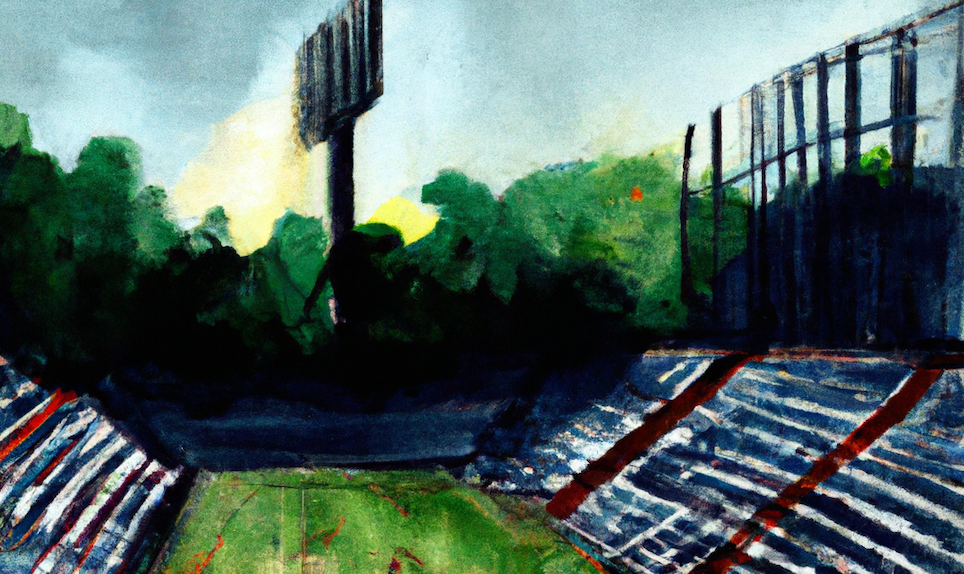

1 October 2022 was the last day for Margaretha, a 17-year-old victim of Kanjuruhan football stadium disaster in Malang, East Java. Margaretha was lying lifeless when her family found her in the hospital that night, clutching a bag, and with her identity documents still intact.

Margaretha’s mother was psychologically traumatised after the tragedy, always blaming herself, and remembering what had happened to her daughter. If she could have forbidden her daughter not to watch the match that day, then it is possible that her daughter would still be safe.

The family of another victim, Okto, was offered psychological assistance from one of the universities in Malang. The family did not take it, because they thought that it would mean Okto’s mother would continue to remember her son’s death. Before leaving for the stadium, Okto borrowed his father’s shoes. The family found Okto lifeless, wearing a white jumper, with his father’s shoes left on. Okto’s body was found at Wava Husada Kepanjen Hospital without any identity documents. His wallet and mobile phone had disappeared.

Their suffering exemplifies the psychological effects felt by the families of the victims in the year after the tragedy, in which 135 people were killed after police fired tear gas on crowds after a pitch invasion.

The trauma of survivors and families feeling the heavy loss of family members has been compounded by intimidation by authorities.

These traumas for the victims’ families have been compounded by their experiences of intimidation by outsiders beginning shortly after the tragedy occurred. Some of the alleged threats and intimidation directed at witnesses and victims’ families are quite diverse, ranging from illegal searches and confiscation of evidence by investigators, intimidation of medical personnel, surveillance and threatening behaviour towards victims’ parents by unknown persons suspected to be police, to intimidation for expressing opinions in the Kanjuruhan trial decision.

One survivor, Devi, felt the deep loss of losing his two daughters to the Kanjuruhan tragedy. In the midst of the autopsy process, Devi’s emotional outburst was so strong witnessing the death of his daughters and this deep sorrow also prompted him to declare that “this tragedy is a massacre” on the part of the police. This psychological pressure was not only experienced by Devi, whose story was reported in Vice News, but also by the families of other victims whose stories were not covered by the media, some of whom also experienced psychological intimidation by the authorities.

One of these families is Maria’s., where field observations have shown that this family not only felt a deep loss for the departure of their family members, but they also felt non-physical intimidation from security personnel after the Kanjuruhan tragedy. In the case of Maria’s family, they expressed their feelings of loss when they learned that Maria (the third of the five children) was taken from her son by the tragedy. The family found it difficult to explain to their son about their mother’s true condition.

When Maria died, her son (aged one year) did not leave the house for almost two months. Until his hands were like scratching, changing skin like that. Then crying for his mama. Yesterday, his body was hot for one week, crying for his mama. Then I said mama he said he was looking for money, looking for work….ooh how come he forgot (crying). (Interview with Maria’s family, 16 May 2023)

Lost lives, lost livelihoods

The Kanjuruhan tragedy on 1 2022 hast left a painful imprint for its victims. A year after the tragedy, the loss of life for the families of those killed and injured by tear gas is not the only impact. The families of the victims continue to experience long-term psychological, social, and economic consequences.

Numerous kinds of government and non-governmental aid have been distributed to the victims. However, the nature of this assistance is still partial and spontaneous as a form of responsibility to the survivors. In addition, the aid distributed has not been able to answer the long-term needs of those who survived, so a sense of justice to them has not been present in handling the aftermath of this tragedy. A series of interviews conducted by Malang Corruption Watch with 20 families of those killed in the Kanjuruhan disaster, conducted over a two week period in May 2023, shows that many families’ socio-economic conditions have changed drastically. In many cases, the person on whom the family relies for income is now gone. Based on information from the victim’s family who was left behind by the victim in the tragedy explained:

So far, my husband has been the backbone of the family. With his death, now I have to struggle harder. Until now, I have not been able to find a permanent job, only as a housemaid to fulfill the family’s needs” (Interview with victim’s wife, Dimas, 16 May 2023).

One of our interviews reveals that one victim’s wife was forced to become the female head of the household to support her only daughter. The wife was forced to make important decisions in the household by herself. Their lives are increasingly isolated.

The plastipelago

Indonesia’s encounter with the “plasticene” has led to a naïve and hasty government effort to rebrand waste as an asset.

One of the victims in Malang’s Tajinan sub-district had just started a motorcycle and carpet washing business for three months before his death at Kanjuruhan stadium. While managing the business, he was financially independent and able to break even, with enough profit for his daily needs after graduating from Vocational High School (SMK). However, after the tragedy, there was no effort to compensate the loss of income according to the income of the victims’ families. In fact, just for the procurement of a machine or work tool, Suyono (the victim’s father) had to ask a state institution. The machine was not an initiative of the state officials who were also part of the litigants in the Kanjuruhan tragedy.

In addition to the uncertainty around income compensation, the certainty of access in the form of legal fees or expenses incurred by victims as part of their participation in the trial of five individuals, including three police officers, implicated in the disaster. There is almost no ease of access victims’ families at the trial. One of the victims’ families in Malang Regency was even encouraged by some unscrupulous state officials to “not exaggerate the problem”, with the implication that there was no guarantee of transportation to attend the trial in Surabaya.

Tali Asih: inadequate assistance to victims

Victims have rights to assistance and compensation, including ensuring free medical treatment and trauma healing for victims and their families. Victims’ rights are regulated in legislation, specifically in Indonesia’s 2014 Law on Witness and Victim Protection (Undang-Undang No 31 Tahun 2014 tentang Perlindungan Saksi dan Korban), which regulates the rights of witnesses and victims to claim protection from the state; these rights are considered part of human rights. The government or the private sector should not just provide compensation, but should handle events and fulfil rights from a victim’s perspective.

Assistance is carried out in the form of giving money, goods, or services, to individuals, families, groups and/or communities to protect them from social risks. The assistance distributed is not merely a substitute for the loss of a loved one’s life, but proof of attention as well as friendship from various parties to the victim’s family.

In this case, various kinds of aid have been distributed to the victims, both monetary and non-monetary. However, the majority of the aid distributed has been in the form of monetary aid, which a diverse array of stakeholders have provided to the families of the Kanjuruhan victims. It can’t be denied that the distribution of cash assistance is the quickest way to fulfill their responsibility to help the families of the victims. However, it has yet to address the needs of the victims’ families—especially long-term needs such as education and careers—nor does it provide full justice for the victims’ families.

In general, there were two parties that have provided assistance to the families of the Kanjuruhan victims. The first is the government. At first glance, almost all levels of government participated in this mission, from the central government to local governments. At the central government level, the Ministry of Social Affairs and the Witness and Victim Protection Agency (LPSK) are the most dominant stakeholders in providing assistance. In an interview with Malang Corruption Watch, Suyono, a father of one Kanjuruhan victim, mentioned the assistance he received from the Ministry of Social Affairs in the form of compensation of Rp10 million to each of the victim’s families, although he also stated that the assistance was also unevenly distributed to all of the victims’ families.

Meanwhile, the majority of assistance from LPSK has come in the form of psychological assistance and trauma recovery services for victims’ families. This assistance was received by almost every victim’s family. However, not all of the victims’ families accepted the assistance, either because they did not need it or because they were afraid that accessing such services would exacerbate their trauma.

At the local government level, the East Java provincial government under the leadership of Governor Khofifah Indah Parawansa, alongside the Malang City and Malang District governments have become central channels for providing assistance to the families of Kanjuruhan victims. Some data obtained as part of Malang Corruption Watch’s interviews shows that many families were given assistance by Khofifah’s provincial government, mostly in the form of cash and business capital assistance. The cash assistance provided ranged from Rp5–10 million for each victim family, while business capital assistance was provided in the form of money, machine tools, and jobs.

Second, assistance was voluntarily provided to victim families by non-governmental parties as a form of their concern for this tragedy. This has included political parties, for instance, Golkar Party, where Malang Regency Leadership Council of Golkar Party (DPC Kabupaten Malang) provided education assistance to the family of one victim, Caca, amounting to Rp10 million per month and the assistance was intended to finance her siblings who were still in school. This assistance, was paid from the internal finances of the DPC Golkar, will last for two years until Caca’s siblings have graduated from school.

Aside from assistance from political parties, private educational institutions such as kindergartens also provided education assistance for the family members of the victims who were still in school. The family of Ningsih, another victim, for example, received education assistance for her younger brother who is still in kindergarten to be extended until he graduated from kindergarten.

Table 1: Summary of the types of assistance received by the families of the victims of the Kanjuruhan tragedy

| No | Types of Help | Helper

|

Number (families of beneficiary victims) | |

| Government agencies | Non-Government | |||

| 1. | Cash | 20 | ||

| 2. | Groceries | 20 | ||

| 3. | Funeral expenses | 2 | ||

| 4. | Education | 7 | ||

| 5. | Work aids | 1 | ||

| 6. | Psychological rehabilitation | 9 | ||

| 7. | Population administration relief | 2 | ||

| 8. | Health/medicine | 1 | ||

| 9. | Tax relief | 1 | ||

| 10. | SIM free | 1 | ||

All these forms of assistance are certainly not enough to make up for the loss of life of the victim for their families. However, due to the voluntary nature of the assistance, the families of the victims accepted it openly. The assistance they receive does not guarantee the fulfillment of long-term needs, that should be safeguarded by the state.

From our interviews, it can be concluded that the types of assistance received were not well planned. Victims’ families’ descriptions of the forms of assistance also vary from one another. There are no standardised mechanisms that can ensure that the various forms of assistance are distributed fairly and transparently to the survivors and victims’ families.

As a result, miscoordination in the field the distribution of assistance to survivors is often apparent, and a lot of assistance was assembled immediately after the tragedy, without being able to be utilised for further long-term needs. In addition to the problem of miscoordination, the provision of this assistance also experiences limitations in the aspect of reach, and makes the existing assistance feel that it does not meet recipients’ shifting needs.

Justice beyond aid

Providing material assistance to those impacted by the Kanjuruhan disaster in this way is not very effective in delivering an element of justice to them. If the process of providing assistance is not done properly, there will be various conflicts caused by unfair decision-making. The fulfillment of victims’ needs will be achieved if there is a coherence in the work of a coordinated distribution system that can consider the characteristics of the individual needs of victims.

Indonesia’s Law No. 11/2009 on Social Welfare (Article 1, section 9) states that social protection is all efforts directed at preventing and dealing with risks from social shocks and vulnerabilities. The shocks and vulnerabilities in question are conditions that occur abruptly, as a result of social, economic, or political crises, disasters, and natural phenomena. Thus, the Ministry of Social Affairs is responsible for formulating policies and programs for the implementation of social welfare and the provision of social assistance.

However, due to the limited resources owned by the Ministry of Social Affairs in providing direct assistance, crowdfunding method has become an alternative to recover Kanjuruhan victims by raising funds from the community.

If we look at the practice of fundraising for victims of the Kanjuruhan tragedy, so far the parties who have channeled aid have directly met the victims or through organisers at the Aremania football team’s supporter club. The victims are in a vulnerable position not only in terms of facing the criminal justice system, but also economically, socially and politically. In addition, many of them currently lack long-term social and economic security because the majority of aid was distributed shortly after the Kanjuruhan tragedy took place.

Policy-wise, the aid distribution system requires coordination from multiple actors who are competent in distributing aid. It is necessary to analsze the burden borne by victims based on the criteria of economic capacity, the number of family members, and the scale of the economic impact of the disaster on them. Fulfillment of victims’ welfare rights is not only about monetary assistance, but there needs to be a clear calculation in measuring losses to victims. Thus, it should consider more vital aspects such as age, income, actual conditions, and the years left before reaching the national life expectancy. If we take the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ compensation system as an example, the calculation of compensation can even reach a very specific amount with a formula that includes the age of the victim, the national life expectancy at the time of death, and the income earned before death.

This compensation, in turn, needs to be jointly fought for by the entire community to ensure the establishment of justice for Kanjuruhan victims from a legal perspective. Thus, the struggle agenda to demand usut tuntas—thorough investigation—as the slogan of the Kanjuruhan tragedy demands collective awareness. This demand should not come from a particular group, but as a manifestation of a struggle that is in line with the will of the victims.

This means that all processes of defending victims must be based on the victims’ perspective. The victims’ perspective means that all forms of voices issued to the public regarding the Kanjuruhan issue comes from the victims. Understanding the true demands of the victims is what is so important to be pursued immediately. After the tragedy, various impacts have been experienced by the victims, but as our interviews have highlighted, they did receive various kinds of assistance from both the government and the community.

However, can anyone measure the price of losing a life? Of course, learning to listen to the voices of the victims is very important for the government to do immediately.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss