With the clock ticking on his reform agenda, 2020 looks set to be President Jokowi’s most pivotal year yet. The new omnibus legislation on the creation of employment, intended to improve the country’s investment climate, has been rejected by Indonesia’s labour unions. In pushing through his pro-investment reform agenda, Jokowi is confronted with the dilemma of moving fast or moving with everyone.

Indonesia appears to be poised at a critical threshold. It is attempting to shift to a higher growth model based on value-added industries from a predominantly natural resource and consumption driven economy. To do so, Indonesia needs fundamental reforms to its political-legal superstructure because a pro-growth and a pro-investment platform needed for job creation cannot coexist with a rigid labour system and other tax and legal barriers. Unfortunately, investment facilitation inevitably puts Jokowi on a collision course with potential losers, as his proposed reforms require some of the generous labour protections put in place since the end of the Suharto Era to be undone. Tensions generated by his reform agenda underscore the difficulty in negotiating development’s uneven distribution of costs and benefits across society.

To put things into context, Jokowi’s economic agenda can be understood as a narrow form of developmentalism combining both limited economic liberalism and economic nationalism. Jokowinomics has two faces—on one hand, it is the face of a country friendly to foreign investment and business interests. Luhut Pandjaitan, Jokowi’s Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, represents that face. He is nicknamed as the “Minister for all Affairs” (menteri segela urusan) because he has been tasked to troubleshoot and improve the inter-ministerial coordination needed to debottleneck investment hurdles.

On the other hand, the face of economic nationalism is none other than Jokowi himself. Jokowi is now waging an undeclared war against imports and raw commodity exports through tariffs and non-tariff measures—he has spoken multiple times in public about Indonesia’s love for foreign oil and exports of raw materials such as nickel, bauxite, and crude palm oil. His goal is to achieve a positive current account balance so that Indonesia is not economically dependent on foreign countries.

If one were to put aside all the headlines, the real barometer of the success of Jokowi’s agenda to remake Indonesia as an investment-friendly destination depends on his ability to push through his legislative agenda by this year. Jokowi only has a narrow policy window to effect structural change on the back of his strong electoral mandate—having the necessary legal umbrella (payung hukum) in place is sorely needed for legal certainty and to effect visible change before he steps down. To ensure that his reform agenda succeeds, he had made deals with Indonesia’s political elite in exchange for legislative support. This can be discerned by Jokowi’s coalition strategy in his second term. The literature on coalition building in multiparty presidencies in Latin America is clear on this point—presidents build minority coalitions when they intend to rule by executive decrees but build majority coalitions when they have a legislative strategy (i.e. to pass laws) in mind.

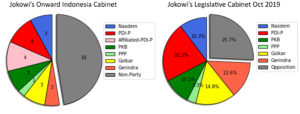

To obtain legislative support, he is prepared to “horse trade aggressively and make unsavoury political pacts with the ruling elite” to carry it out. Jokowi has already paid the king’s ransom required, building a large government coalition in Parliament comprising roughly 74% of all seats. By making an unsavoury alliance with his ex-presidential rival Prabowo Subianto, who leads the 3rd largest party in Parliament, Jokowi has managed to dilute the influence of political parties in his coalition. The PDI-P, the largest party in Parliament with only 22.3% of the seats, will not be able to veto his legislative agenda. The size of the governing coalition affords Jokowi the opportunity to exploit party disunity to position himself as the main balancer, while forestalling any party threatening to withdraw their support.

Data compiled by author. Note that the seat allocation in Jokowi’s cabinet is roughly proportional to the party’s weighting in parliament, except for Gerindra.

Although Jokowi has successfully made deals with the political elite, he has neglected a source of potential opposition to his reform agenda, namely Indonesia’s labour unions. The contested nature of development is best underlined by two pieces of super-priority legislation known as omnibus legislation. The legislations are intended to be game-changers in simplification of the legal morasses that have plagued the ease of foreign investments and for Indonesia’s economic transformation more generally. The two pieces of legislation concerns the law on the creation of employment and tax provisions for strengthening the economy (RUU tentang Cipta Lapangan Kerja, RUU tentang Ketentuan dan Fasilitas Perpajakan Untuk Penguatan). They have already entered the Priority National Legislation Program for 2020, meaning that the Indonesian Parliament intends to discuss and pass them this year.

In defence of Jokowinomics

Jokowi's statist developmentalism isn't perfect, but it's a realistic response to the political economy barriers that have held up private investment in infrastructure.

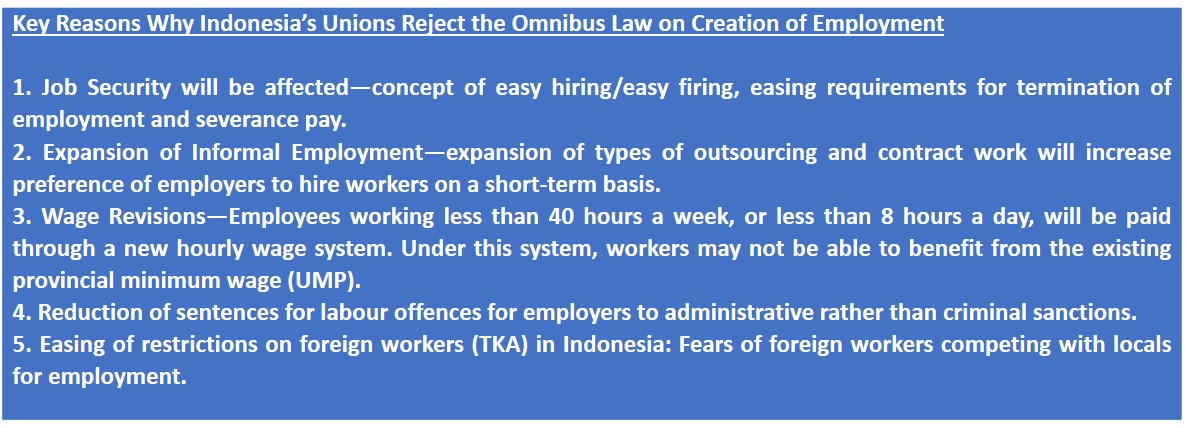

However, efforts to amend the 2003 Law on Employment has been vigorously rejected by Indonesia’s labour unions. The employment cluster of the omnibus law, comprising of amendments and repeals of the 2003 Law on Employment, has been controversial for existing workers because the regulations for this cluster have been revised based on the principle of “flexible working hours, easy hiring and easy firing”. The workers have legitimate concerns. The Omnibus Law Task Force (Satuan Tugas Bersama Omnibus Law) formed by the Coordinating Minister of Economic Affairs, Airlangga Hartarto, is dominated by business interests from the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (KADIN) and other business associations. Information from the media suggests that clauses in the omnibus legislation needs KADIN’s approval.

Compiled by the author

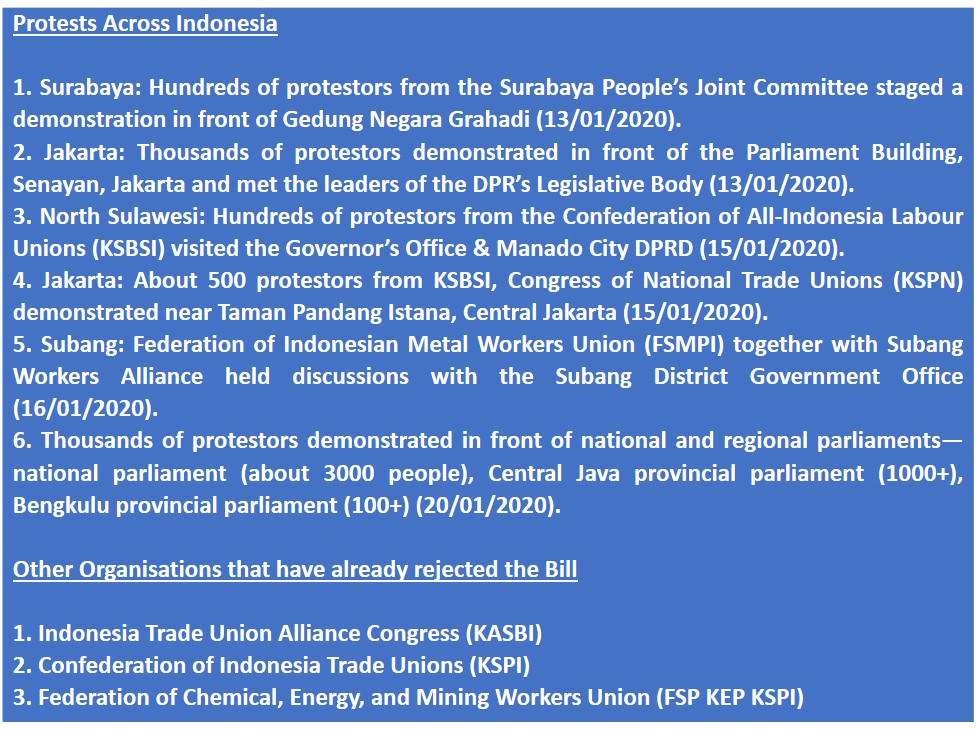

Unhappiness over the proposed regulations had brought Indonesia’s labour unions out on the streets. On 13th January 2020, an alliance of 12 labour unions called the Labour Movement for the People (Gebrak: Gerakan Buruh untuk Rakyat) protested outside the Indonesian Parliament. Indonesia’s labour unions have been sceptical of Jokowi’s developmental agenda. On 1st May 2018 (Labour Day), 1 year before the 2019 Presidential Elections, an estimated 3 million Indonesian workers took to the streets to pressure the government for more supportive policies. Prabowo Subianto, Jokowi’s presidential rival, promised to support pro-worker policies at Jakarta’s Istora Gelora Bung Karno Stadium. In response, Chairman Said Iqbal of the Confederation of Indonesia Trade Unions (KSPI), declared that KSPI would support him in his election. The political symbolism of that event was clear—Prabowo Subianto was perceived as a presidential candidate more favourable to workers than Jokowi.

Since then, KPSI had been at the forefront of the opposition to the omnibus legislation on the creation of employment. In late December 2019, Said Iqbal judged the draft omnibus law on creation of employment as threatening the welfare of workers. He said that the KPSI planned to take action with almost 100 000 workers in 20 provinces. The planned demonstrations were hoped to pressure the Indonesian Parliament to reject the omnibus legislation and was carried out on 20/01/2020. The protests turned out much smaller in scale that originally planned, with 6000 police personnel deployed to maintain order around the national parliament.

Compiled by the author

The effectiveness of any ground-up movement in influencing the passage of laws during the Jokowi administration will likely be limited. The Chairman of the Legislative Body of the Indonesian Parliament, an 80-member committee in charge of matters pertaining to legislation, had promised to involve representatives of the workers once they received the draft omnibus legislation. However, the Parliament is also being pressured by Jokowi to complete discussions of the two omnibus legislation within 100 days (by May 2020), a deeply problematic proposition. It gives little time for the public to digest the 1200 plus articles of the bill as well as to exercise their right to make submissions about laws under deliberation (Article 96, Law No. 12/2011).

There is now a real concern that Jokowi will push through his legislative agenda with or without the support of the labour unions. During the era of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, in response to widespread protests regarding the passage of the law on the abolition of regional elections, President SBY re-established direct regional elections through an interim emergency law (Perppu). In late September 2019, tens of thousands of students across major cities in Indonesia protested the stealth passage of controversial amendments to the Law on the Anti-Corruption Commission. In contrast, President Jokowi prevaricated and did not issue a Perppu. He was content to let the police use tear gas, water cannons, and rubber bullets to disperse the protestors.

At the same time, there is also a real risk that the momentum of Jokowi’s reform agenda becoming torpedoed by masses of angry Indonesian workers who have most to lose from the relaxation of labour protections and have not been involved in the drafting process. A coalition of civil society groups have also rejected the legislation due to concerns about the lack of public participation and potential environmental damage. Any kind of negotiated process that will be satisfactory to the unions are likely to be protracted, tortured, and with no easy resolution in mind. With the clock ticking on his reform agenda, Jokowi may have to choose between moving fast or moving with everyone. What he chooses will have serious consequences on Indonesia’s future trajectory.

Three years ago, Emanuel Macron seized the French presidency by styling himself as a political outsider and liberal reformer. Yet, by late 2018, a protest triggered by high fuel prices morphed into the Yellow Vest Movement, as many French became frustrated by grinding inequality, dissatisfaction with his pro-business policies, and an unbridgeable divide between the masses and the elite. Since then, Macron’s reform agenda had been fatally compromised by his low popularity rating and the consolidation of hardcore opposition to his policies.

With Macron’s France in mind, it is not far-fetched to imagine a coalition of the orang kecil, from labour unions to civil society, rising to reject pro-investment reforms detrimental to their interests. One key difference between President Jokowi and President Macron is that the former had built up a formidable store of political capital over his first term and is immensely popular in Indonesia. President Jokowi should invite labour and civil society representatives to submit feedback to the parliament as the bill is being discussed and personally utilise his power of persuasion so that the whole country is able to move forward together (Indonesia Maju). If legislation is passed without consulting or obtaining the support of the unions, there could be sustained and countrywide protests. A worst-case scenario is that workers’ resistance becomes so serious that Jokowi is forced to back down on his legislative agenda.

The bottom line is that at this juncture there is a need to strike a balance between moving fast and moving together. Although Jokowi only has a small window of opportunity to succeed and achieve his economic reform agenda, all might be for nought if it is achieved without public consultation and public support. Jokowi’s Indonesia need not go way of Macron’s France.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss