The biggest takeaway from Indonesia’s 2019 election was Joko Widodo’s reconciliation with Prabowo Subianto after the former’s victory. Let’s put this momentous event in perspective. The two men had been locked in a tense political rivalry ever since the two contested the presidency in the 2014 general elections. Jokowi, a pragmatic reformer, urged for infrastructure development to equalise the nation’s social development whilst Prabowo, the ex-military general, promised to forge a new Indonesia with a muscular nationalist identity backed by strong undercurrents of Islamic zeal. The 2014 election was deemed by many as a precarious inflection point for Indonesia’s democracy, partly because the two men’s populist campaign styles spilled their political differences into the social realm and transformed political relations ever since. The effect of the 2014 elections upped the stakes by the time of the 2019 national election as Indonesians’ social relations had become differentiated by their political allegiance either to Jokowi or Prabowo. This effectively transformed much of the country’s social relations and public discourse in the image of America’s post-Trump politics. Both Jokowi and Prabowo, still in a political one-upmanship to the very last minute of the election, then sculpted Indonesia as if it were divided into two opposing sides: nationalist or religious.

The conclusion of the 2019 election was controversial because both men declared victory. Jokowi had won the election by a comfortable 10-point margin according to quick polls and the Electoral Commission but Prabowo quickly declared victory shortly after the election to the surprise of many. He claimed there had been structured and systematic cheating to deprive him of votes and then urged his followers to demonstrate against the great injustice of the possibility of losing. And demonstrate they did. Prabowo’s supporters shut down parts of Jakarta for three days as they protested against the election and democracy itself. The episode elicited fears reminiscent of the violent riots in the aftermath of student-led demonstrations against Soeharto in 1998. Violence broke out in some parts of central Jakarta resulting in the death of a few of the protesters (albeit under mysterious circumstances). Thankfully, chaos quickly subsided, but a tense air of apprehension never left the country.

If seen from the political realist perspective, the reconciliation may be interpreted as a positive end to a bitter and divisive election. There were sceptics pointing out that a single, rare moment of reconciliation could bridge political cleavages overnight. After all, divisions between political foes are not so easily forgiven. For example, Jokowi and Prabowo’s rapprochement has pushed the conservative Islamic Ulama Convention to withdraw their support for Prabowo, claiming that he had betrayed their aspiration. They explicitly rejected the electoral results, non-Islamic ideologies, capitalism, and formally urged for a Caliphate to be the only form of government in Indonesia. Prabowo and political Islamic groups’ divorce could only indicate that political opposition has now diversified and become entrenched in identity-based politics rather than simply political opportunism. Why, then, would Jokowi be interested in reconciliation with Prabowo? Wouldn’t it have been easier to deal with a consolidated constellation of opposition organised around Prabowo at its core? Was the decision to reconcile a beginning of political horse trading? Was it born out of a genuine concern for the country’s paralysis caused by political division? Or, did it tell us of a higher political game between leaders’ positioning in early preparation for 2024 elections?

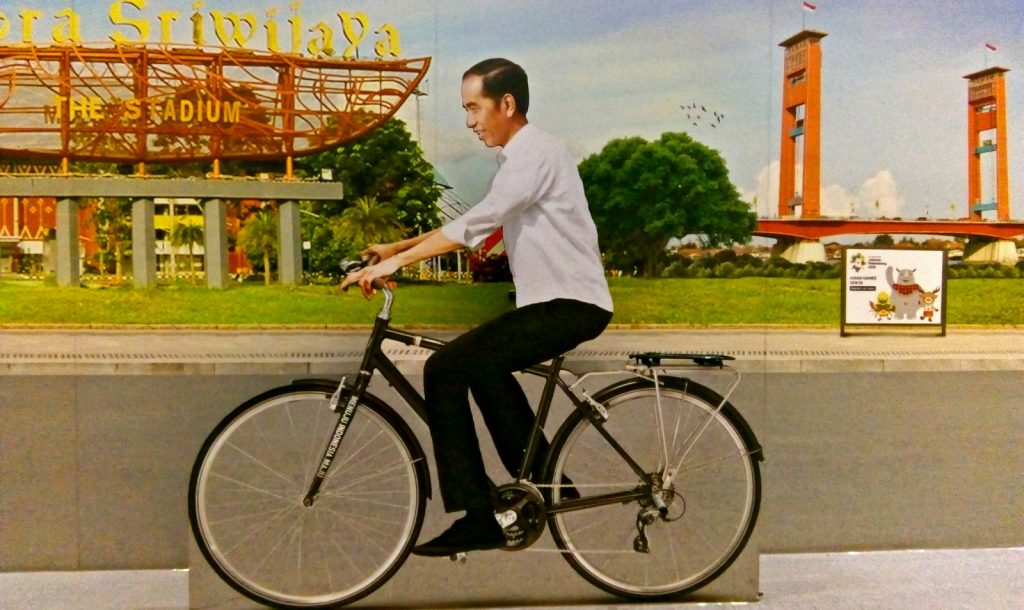

Prabowo meets Jokowi from Wikimedia Commons

Responding to the above questions, I argue that the Jokowi-Prabowo rapprochement is an example of a Javanese philosophical approach to power at play. A cultural lens gives us a richer analysis because it provides us with a cultural framework to analyse actor motivations. From a Javanese perspective, Jokowi’s move was made from a position of strength to absorb Prabowo and boost his own power in the national polity. I will explain my argument in three steps. First, Java’s dominance in Indonesia’s politics leads to a different political dynamic in Indonesia. This difference has guided Indonesian presidents to behave as Javanese rulers rather than as democratic leaders and Jokowi is no exception to this. Second, political events are part of Javanese rituals to evoke power. By looking at political events as part of a Javanese ritual, Jokowi’s rationale to accommodate Prabowo makes sense because it appeals to the former’s attempt to boost his own power rather than rejuvenating Indonesia’s democracy by cultivating a healthy government-opposition balance. Third, cultural analysis gives insight on how Indonesia’s leaders legitimise themselves. Political changes may only happen following the Javanese cultural instincts instead of following institutional or rational logic because if any big changes were to occur in public politics, they require the support of Indonesia’s citizens and the best path is through a cultural approach rather than political rationality.

Characteristics of Javanese Power

Since the Javanese are a cultural majority in Indonesia, any analysis on Indonesian politics should not be separated from its cultural elements. At its core, the Javanese cultural definition of power is different to the Western conception of power. The West sees power as an abstraction. It is a by-product of social intercourse. On that note, power is plentiful because it is constructed by mutually-defined might, pegged to societal norms and values. Power is intimately related to wealth, the lethality of weaponry one possesses in their arsenal, and the exclusivity of one’s social status. Since the aim of Western power is to grant the individual the ability to get others to do what they would not otherwise do, the Western political telos is then concerned with consequences of power. What are some factors in a situation that necessitate the use of moral and just power? When is it moral and just to use power? Who wins and who loses?

‘Green Islam’: Islamic environmentalism in Indonesia

Indonesia promises a future of Quran-inspired sustainability and renewables but is constrained by fossil fuel interests in government.

On the other hand, power, to a Javanese, is a constant in the universe. It is not constructed by social intercourse or defined by the quantity of asset ownership. Power emanates from within the person and is found in sacred objects. It is also the non-living energy that drives our environment. Power simply exists and there are no questions on whether a person’s action is morally just or whether its consequences are ethically sound. Thus, the ontological concern for power is in the process of accumulating it. Power is to be possessed by the leader if he wants to be effective because concentrated power in the hand of the leader means he owns the most amount of power over others in the nation since power exists in a limited, fixed quantity. Therefore, the process of accruing power is critical because it determines how capable the leader is to rule over the nation. There is no question of whether the winner and the loser stood on the right or wrong sides of morality. The only analytical focus for a Javanese observer, then, is whether the individual can undertake the process of accumulating and maintaining a taut balance of converging sources of power in him despite difficult trials ahead.

Consequently, a Javanese leader will act differently to a Western one. A true Javanese leader is locked in a perpetual quest to retain power, whereas a Western democratic leader would emphasise respect for systems and democratic norms first. The Javanese prescription of concentrating power is achieved by increasing the number of people under the leader’s influence, collecting more sacred objects (pusaka) to add to their arsenal, and displaying publicly that they have the capacity to maintain so many powerful people and objects without losing their sense of self along the way. The crucial element here is therefore the leader’s self-mastery. Power in the Javanese sense is an all-pervasive spiritual energy that transcends physical boundaries, thus making the individual leader’s interaction a determining factor to the state of their external surroundings. A chaotic inner self within the leader would also produce chaos in the external world.

The ideal Javanese power approach prescribes the leader to be an individual with extraordinary discipline, able to maintain a veneer of calmness to reflect a composed inner self. The ruler shall not distract himself with worldly affairs, strong emotions, pursuit of self-indulgence, or undertake certain decisions to conceal his self-interested agenda (pamrih). This asceticism anchors the leader’s inner self because a distracted leader diffuses his attention and his ability to accumulate power along with it. Once lost, power is difficult to recover because collecting power for it to be concentrated at the hands of the rightful leader often requires a literal restoration of order to a chaotic world. Therefore, the Javanese ruler must be adept at two things. He must be able to sustain his concentration as the focal point of the nation’s energy converges on him and show publicly that he is able to hold the tension as a result of accommodating so many contradictions of power.

The ideal Javanese ruler would not resort to outright violence or coercion against his foes because such methods are deemed kasar (unrefined, coarse, brutish). The notion of Javanese power is found in the wayang (shadow puppet) show. The stories would be centred on protagonists who achieve victory by utilising the halus (refined, smooth, elegant) power. It would grant them invulnerability against their opponents’ excessive, kasar force. Thus, the ideal Javanese ruler would appear indifferent in the face of grave danger. They know the mark of true strength comes from within by harnessing the energy from the world around them.

Jokowi’s leadership history has been remarkable because he has embodied this ideal consistently and successfully at all levels of governance. Jokowi’s body language is exemplary even though his speech says otherwise at times. A key example was Jokowi’s declaration to strike Communists whenever they pop up in the national scene. Such threats are an indication of flagrant use of excessive force that hints at kasar methods to confront opponents but stops short from actually doing so. As mayor of Solo, he transformed the city from financial and reputational ruin by personally approaching Solo’s business community to gain support, and pushed bureaucratic reform from within the city’s government. As governor of Jakarta, Jokowi’s leadership was more subdued compared to Basuki Tjahaja Purnama’s (Ahok) more bombastic leadership. Jokowi again harnessed public momentum for his leadership by committing to blusukan (sudden, unplanned visits) to markets, slums, and various government offices within the province to publicly highlight government inefficiency without tackling the problem head-on.

Jokowi’s reliance on the Javanese approach to power is even more pronounced in his presidency. Ahok’s case was controversial because he was indicted on religious blasphemy due to his careless comment on religious affairs in the lead up to the heated 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial elections. Already seen as a proxy war in the lead up to the 2019 general elections, Ahok’s controversial comment went viral and incited a wave of demonstrations climaxing in the 212 Movement, organised by conservative Islamists and backed by a network of oligarchs. Prabowo threw his support behind the 212 Movement, further dividing the Prabowo-Jokowi candidacy on identity grounds. Furthermore, the online hashtag #2019gantipresiden (Change the President in 2019), came to life as a Twitter handle to organise anti-Jokowi tweets but morphed into a catch-all phrase to contain all of Jokowi’s opponents offline (as well as becoming the unofficial, unsaid slogan of Prabowo’s campaign later).

Jokowi’s reaction to the 212 Movement defied his reformist identity. He took the time to meet with demonstrators, which was criticised by progressives as a sign of regression. He made sure that he was photographed with high-ranking organisers of the 212 Movement, thus remaining at the centre of attention at the demonstration. This example was baffling because Jokowi could have flexed his presidential privileges to shut down the demonstrations. Indeed, he was noted to have exercised more executive privileges, for example, by intervening in Golkar’s leadership spill — a strategy unseen since the New Order. However, as a Javanese leader, Jokowi’s actions are clear. Both episodes showed that Jokowi’s reactions came from the Javanese logic of halus conduct. He defeated his opponents, not by overwhelming them head-on, but by using presidential executive powers to deflect and redirect opponents from ever having the opportunity to oppose Jokowi later. Lastly, his refusal to shut down the #2019gantipresiden showed that he was unflappable despite serious threats against his presidency. All of these characteristics showed the extent of Jokowi’s presidential habit: confronting opponents by halus conduct, misdirection, and accommodating foes as strategies to outwit opponents from a position of strength.

Political Reconciliation as Javanese Power Ritual

Since public and private realms are intertwined through the leader and halus is so potent in Javanese political conduct, leaders’ behaviour is then part of a set of complex rituals to conjure power and to link together the public and private realms of power. Jokowi’s rapprochement with Prabowo follows this logic. There were indications that political reconciliation was likely to happen moments after the May demonstrations had ended. However, it ebbed briefly during the Constitutional Court hearing before the rumours surged again after the conclusion of Prabowo’s legal challenge. If the ordeal had followed rational, realist politics, then Jokowi and Prabowo would have manoeuvred their respective camps away from the possibility of reconciliation. Jokowi would have braced himself for a difficult five-year administration coloured by stubborn opposition led by Prabowo motivated to unseat the government in every way possible.

But notice that rumours of the rapprochement were publicly disclosed despite the highly sensitive nature of the issue. This is the first indication of how the boundaries of private and public in politicking are often undifferentiated. And when the reconciliation finally happened, it was not a formal occasion marked by stiff pleasantries or peppered by sets of ceremonies. Most importantly, it was an understated casual affair. Jokowi hosted Prabowo on a stroll through Jakarta on the new MRT system before finally treating him to a lunch at a restaurant nearby. The ritual of the rapprochement is found in the details of the occasion and, along with it, hints of the Javanese logic animating the two men regardless of behind-the-scenes political negotiations or each leaders’ intentions.

The casual walk at the MRT presented the two as being with the people. It was a move to restore honour between the two leaders after a no-holds-barred election that divided the country. It was also a way to show to both supporter camps that rivalry is part of the political vernacular and that political division should not be taken so seriously. The lunch between Jokowi and Prabowo was also unremarkable by national political standards because it was hosted in a restaurant that was frequented by Jakarta’s middle class. The Semar imagery on top of their table was an auspicious touch declaring two things. The two men’s relationship shows that they have never escaped the wayang story that has defined Indonesia’s presidencies so far. Furthermore, whilst they were not physically in the confines of the presidential palace, they had never left Jokowi’s sultanate. Overall, the reconciliation was a show of power that Jokowi had finally subdued Prabowo by accommodating him and making amends after a protracted hostility in the lead-up to the national election. The occasion appeared smooth and effortless. And it effectively guided the conversation away from political division and recalibrated the focus back to Jokowi himself. Because Javanese philosophy calls for a “single, pervasive source of power and authority” (Anderson 1990, p. 36), then this episode showed us how halus power triumphed in the end — hence the occasion’s profundity in Javanese polity.

Culture as Source of Political Legitimacy

A cultural interpretation of Jokowi’s rapprochement with Prabowo thus gives Jokowi social capital for him to build political legitimacy. A president steeped in Javanese culture is in close proximity to the Javanese voter base—comprising most of Indonesia’s population—and giving him a strong foundation of support for his policies later. For Jokowi, the reconciliation episode may reflect his desire to consolidate his position as the nation’s president and as a cultural figure to ensure his policies’ success. The cultural approach consolidates Jokowi’s wahyu (divine right to rule) as president. But, as Seno Gumira Ajidarma observed, how seriously should we take Jokowi’s willingness to open his position to Prabowo from a cultural perspective? How much of Jokowi’s Javanese posturing could be interpreted as part of a political power play? And, if Jokowi was truly deliberate in playing the Javanese card, shouldn’t he preach national unity instead of emphasising one cultural group over others? Then, on that note, how much of Jokowi’s political behaviour was a calculated strategy to gain public approval and how much of it was for the pursuit of greater goals?

Jokowi speaking to the press by Eduardo M. C.

Let us address the questions above in reverse. Had it been a matter of public debate, then Jokowi would have accommodated various Islamist conservative activists to appeal to them and build a solid political base to carve an us-and-them division as an exclusive populist — just as Anies Baswedan had done to win the Jakarta gubernatorial race in 2017. Jokowi’s embrace of multiple, opposing agendas here could then be argued as part of a Machiavellian move to bolster his position and the rapprochement simply coincided with Javanese philosophy. As a result, the emphasis on Javanese-ness could be effective as a two-pronged strategy: to boost Jokowi’s cultural standing without delving too much into the rising current of political Islam, and to claim historical legitimacy as previous Indonesian presidents used Javanese philosophy as a way to define their political strategy from their public behaviour by consciously drawing parallels of their administrations with wayang performances from Mahabharata. On this note, Jokowi’s reconciliation with Prabowo is not a special position to differentiate the cultural aspect in his presidency. All of Jokowi’s actions and decisions following this episode serve as a reminder of how little Indonesia’s politics have changed since Reformasi.

What sets the Jokowi-Prabowo rapprochement as a unique occasion? The reconciliation gave Jokowi a way to accommodate Prabowo because only then could Jokowi claim to become a true Javanese leader. The lesson here is not whether Javanese elements have supplanted other cultural groups as an avatar of Indonesia’s national identity. It is in the pervasiveness of Javanese culture in Indonesia’s political identity, because its presidents have consistently appealed to cultural tropes to construct a cultural persona in order to legitimise their rule — but that is not the only issue here. The crucial importance of the reconciliation is that it signalled what has long been observed but never before so widely, publicly, and explicitly acknowledged by Jokowi: that his leadership follows a distinctly Javanese cultural method, morality, and ethics and consequently defined his political relations by this philosophy rather than democratic rationale.

Recalling Soedjatmoko’s observation, the gap to bridge between the Javanese cultural approach to politics and modernity remains a challenge yet to be answered. The rapprochement presents to us a clear indicator that the Javanese philosophy of power is able to resist political and institutional reform, political Islam, and technological development and has become the de facto perspective to approaching political relations in Indonesia. The question then is less to do with ascertaining the seriousness or the motivations driving Jokowi’s decision to rely on cultural tropes. Instead, we should engage with this new awareness of Javanese philosophy in Indonesian politics: how do we take into account the cultural approach when its understanding of power and social relations are so different to democratic norms and rationales? What does Javanese philosophy tell us of the limits and definition of power in Indonesia? And finally, how does culture guide us to understand incoming political and social changes in the country’s maturing politics?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss