This article is based on seminar titled “Jawi: sacred and secular,” which will be presented in the ANU Malaysia Institute Seminar Series 2021 on Tuesday, 27 July, 2021 – 17:00 to 18:10 (AEST). You can register to attend the seminar via the event page.

One of the controversies that embroiled Malaysia’s Pakatan Harapan government came from a rather unexpected source—Jawi. This adapted Arabic script was, from at least the 16th century the most common way of writing Malay, but has been displaced over the course of the 20th century by Rumi, or Roman script. The move from Jawi to Rumi as the default representation ofthe Malay language occurred not as a result of colonial policy, but from Malays themselves as part of a modernising agenda. It was the Kongres Bahasa of 1954 that ratified the use of Rumi alongside Jawi in the name of progress, and the Barisan Nasional governments of the 1970s and 80s that sidelined Jawi within the national curriculum.

National harmony: race, politics and campaigning in Malaysia

A new report analyses debates around social cohesion and a failed proposal for a National Harmony Commission in Malaysia in light of Pakatan Harapan's collapse

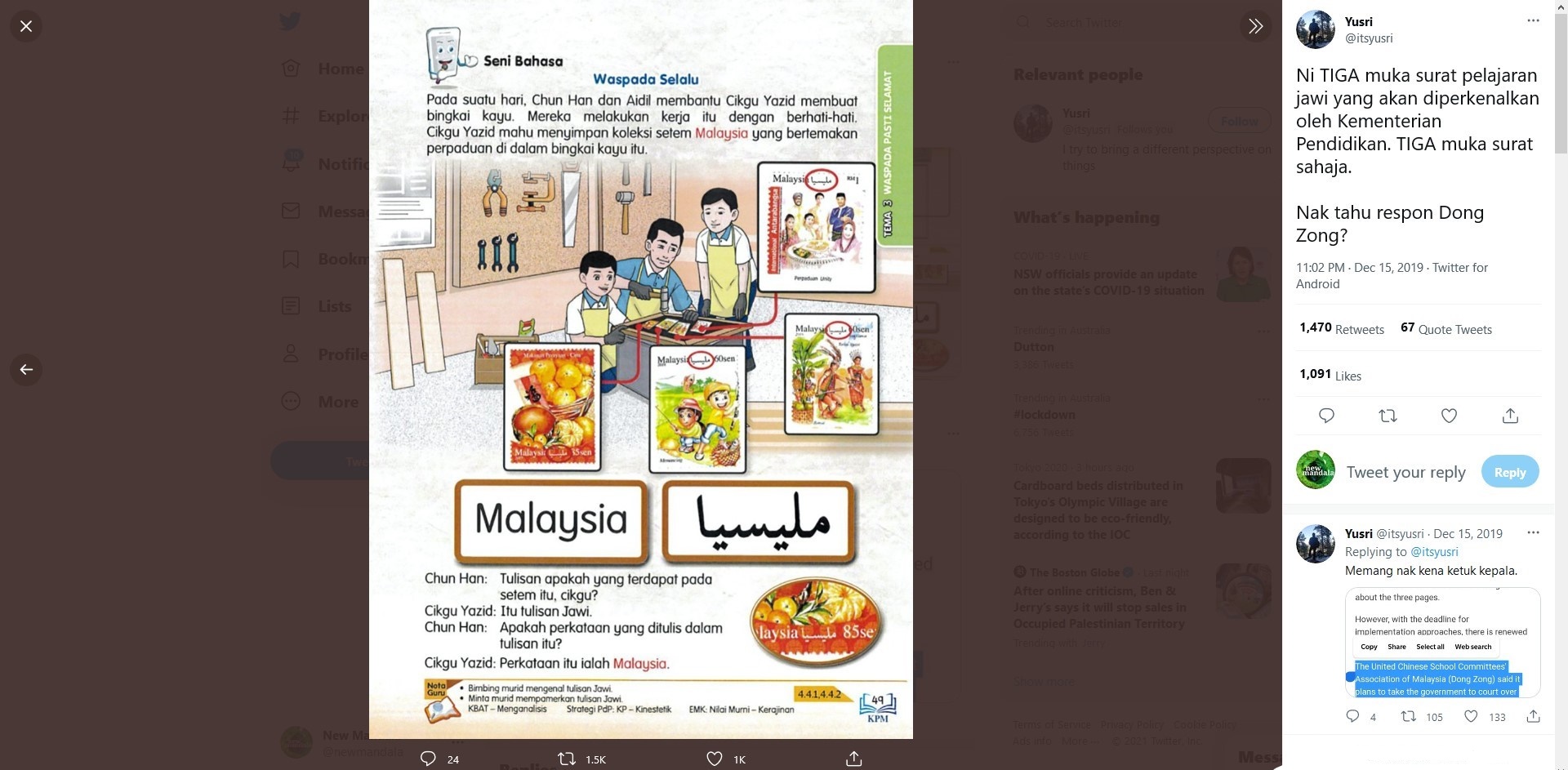

In 2019, when it emerged that the Ministry of Education—then headed by Dr Maszlee Malik, who was already suspected in some quarters for being a crypto-Islamist—had introduced several pages on Jawi in the Bahasa Malaysia textbook for Standard Four, outrage ensued. Some—most prominently Chinese-language educationalists—saw this as the Islamisation of the government curriculum by stealth. Others—most prominently Malay ethnochauvinists—asserted that Jawi script was intrinsically Islamic and should not be profaned by being taught to non-Muslims. Many other Malaysians (myself included) were rather bemused that Jawi had become a lightning rod for identitarian fury, particularly given the content of the textbook pages in question.

Figure 1: A Tweet shows some of the controversial text book images.

These [see Fig. 1] were staunchly (and even comically) nationalistic and secular: Cikgu Yazid (Malay) teaching schoolchildren Chun Han (Chinese) and Aidil (Malay) to read the word “Malaysia” written in Jawi on stamps; Gauri’s older brother (Indian) showing her the words “ringgit Malaysia” and “Bank Negara Malaysia” in Jawi on the banknotes; and another pupil (ethnicity unspecified!) learning to read the national motto (‘Bersekutu bertambah mutu’) in Jawi. A bystander blissfully ignorant of Malaysia’s toxic mix of racial, linguistic and religious politics might ask: what could there be to object to here?

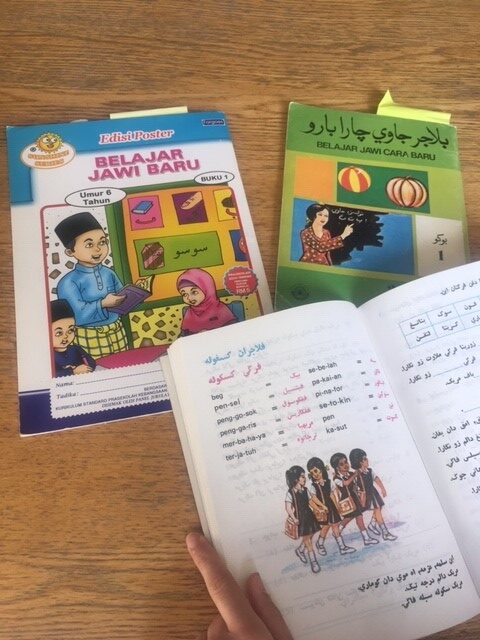

In seeking to reintroduce Jawi to the national curriculum in 2019, the PH Ministry for Education seems to have been attempting to return to the way things were in the first Mahathir era. Up to the early 1980s, Malaysian government curriculum textbooks framed Jawi script as part of Bahasa Malaysia, a national rather than communal attribute, linguistic rather than religious. One 1983 Standard Three Jawi textbook, for instance, depicts a multiethnic group of uniformed schoolgirls—Salmah (Malay), Uzmah (Malay), Ah Moi (Chinese) and Kumari (Indian) [see Fig. 2]. It also has a reading comprehension featuring a dog, which would likely not pass muster now, as many Malay Muslims regard dogs as unclean.

Figure 2: Bottom right, the 1983 text book with illustrations of multiethnic school girls; and top left, Muslim children learning Jawi on the cover of a 2014 Jawi textbook.

This secular nationalist orientation changed after Jawi was removed from the compulsory curriculum in the mid-1980s. Although it was once taught only taught as an additional subject, especially in Islamic schools, after its removal the production of textbooks was taken over by private companies, and emphasised the supposedly intrinsically Islamic nature of the script. The 2014 textbook intended for six year olds, for instance, features a girl in a headscarf and two boys wearing songkok on the cover. Within, the guidance for teachers stresses learning about the Prophet’s life, and about Islamic ethics and conduct. Here, Jawi, Islam and Malayness are firmly intertwined.

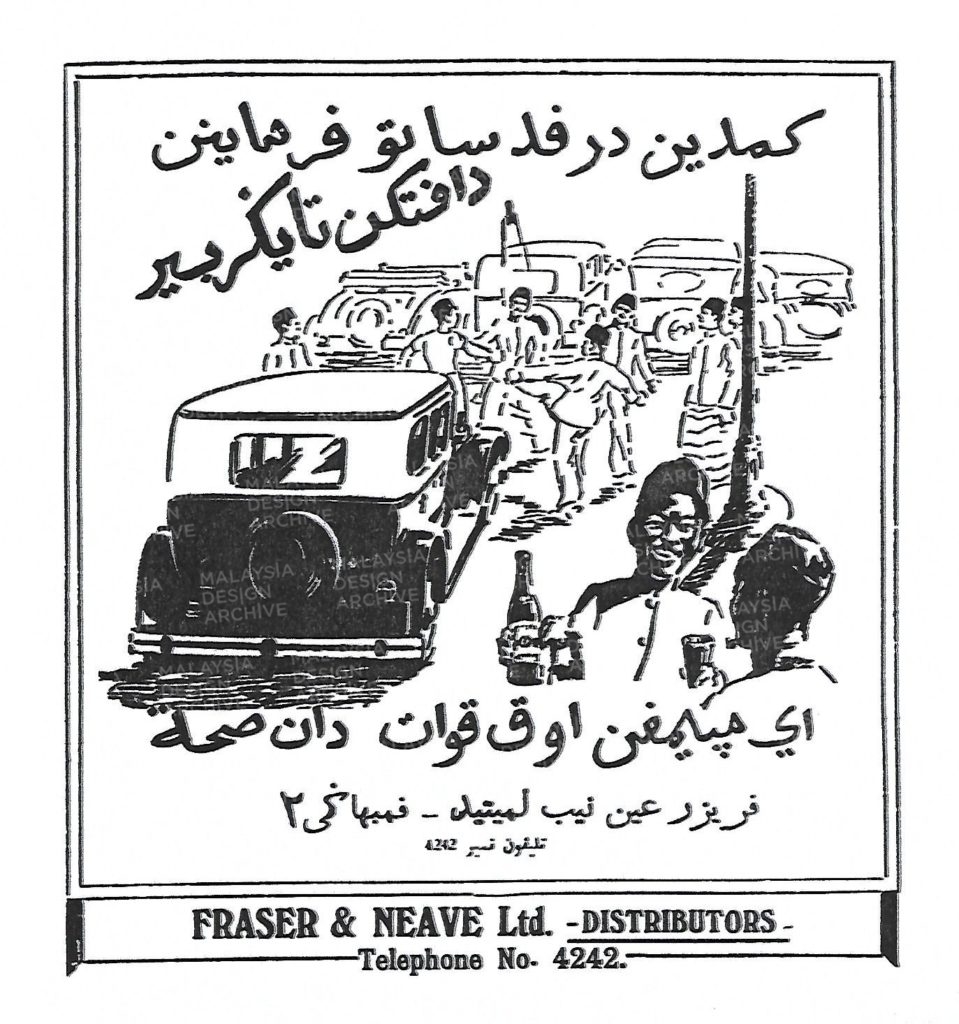

Figure 3: Advertisement for Tiger Beer. With permission from the Malaysia Design Archive.

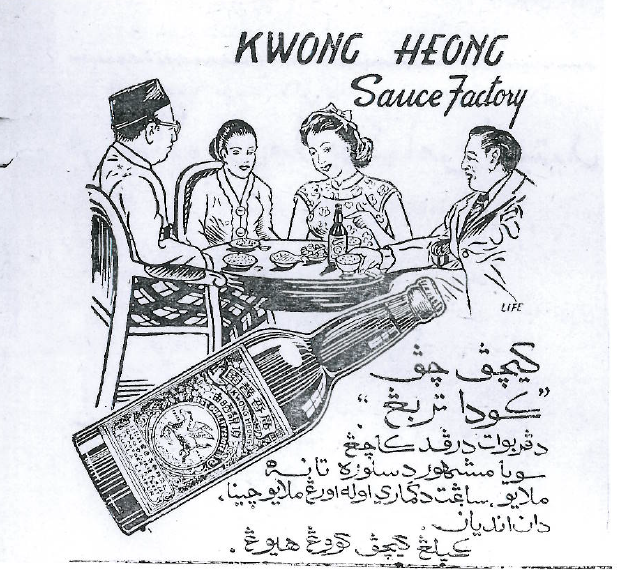

While there is certainly a close and abiding association between Islam and Jawi, since the Arabic language and script are intrinsic to the Qur‘an, in its centuries long presence in Southeast Asia Jawi has been used by Muslims and non-Muslims alike, for all sorts of purposes. Some of those most exercised by the 2019 controversy may have been surprised to know that, for instance, Jawi was used for to advertise beer in the 1930s (“Tiger Beer… keeps you strong and healthy”) [Figure 3], to promote Chinese-made soya sauce to multiethnic consumers in the 1950s (“enjoyed by Malays, Chinese and Indians”) [Figure 4], and for erotica in the 1960s (Godaan Wanita et al).

Figure 4: Kicap Cap Kuda Terbang advertisement, Majlis, 4 August 1950.

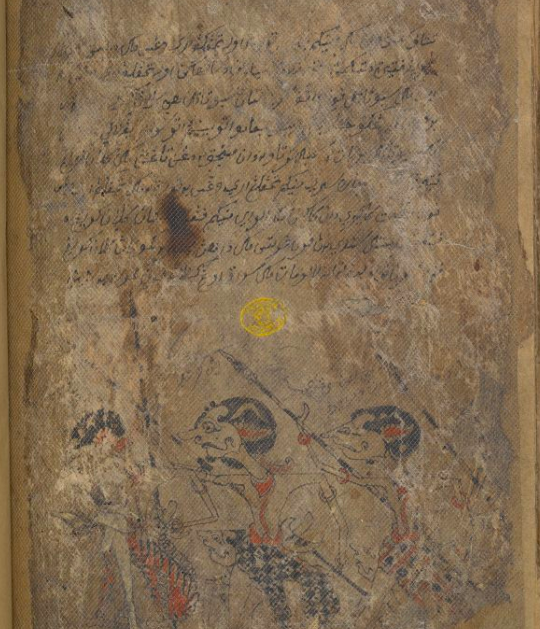

Even earlier than this, when Jawi was the only script for Malay, it was used as a matter of course for secular literature, like the perennially popular Panji tales, set in a pre-Islamic Java [Figure 5], as well as for Islamic texts. It is only now, when Malay in Rumi occupies all secular cultural space—dime novels, comic books, newspapers, advertisements—that Jawi has come to be seen as exclusively Islamic.

Figure 5: 19th century Malay Panji manuscript from Kelantan, British Library.

At the height of Malaysia’s Covid epidemic, exacerbated by an increasingly dysfunctional government, the Jawi controversy of 2019 seems trivial and distant. But language—and by extension scripts used for languages—in education have always been highly contentious issues in Malaysia, with real-world consequences. The Jawi controversy may have been a factor in Dr Maszlee’s resignation, and perhaps served as a bellwether for the fragility of the PH coalition. The furore over a few seemingly innocuous pages in a textbook provide an indication of just how polarised Malaysian society has become, of just how difficult it is for Salmah, Uzmah, Ah Moi and Kumari to walk together to school, or for their elders to enjoy a meal together.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss