Shipwrecks are incredible resources for scholars of the past, providing a unique insight into a single moment in time. They are often described as time capsules, because they encapsulate so much information about the life of the crew, the technology used to construct the vessel, and the unique make-up of each ship’s cargo. These can tell us about the historical connections between people, ideas and objects. Unlike monuments such as temples or mausoleums, which are purposely constructed in the present for the future, a shipwreck is the result of an accidental event. The legacy of a shipwreck is therefore both unintentional and, in a way, more indicative of life as it ‘actually was’, rather than as the people of the past wished us to see it.

One of the biggest challenges lies in accurately dating ancient shipwrecks. This week, new research coming out of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago is causing ripples in the maritime archaeology world, because it suggests that the Java Sea Wreck travelled almost a century earlier than previously believed.

This was a Southeast Asian trading vessel carrying a large cargo of Chinese ceramics and iron, as well as luxury items such as ivory and resin from outside China.

Some of the many Chinese ceramics recovered from the Java Sea Wreck. Source: Maritime Explorations

Following the wreck’s salvage from Indonesian waters in 1996, radiocarbon analysis was conducted on a piece of resin. Results suggested that the ship dated to the mid- to late- 13th century.

Although the outer layer of the resin was affected by centuries spent underwater, the centre remained ‘lustrous and fragrant’. Source: Field Museum

However, today’s researchers – led by Boone Research Scientist in Asian Anthropology, Lisa Niziolek – have used a variety of techniques to suggest that the ship’s journey could be brought forward by almost 100 years, ‘possibly as early as 1162 CE’. These techniques include radiocarbon dating of new samples, comparative analysis with ceramics from nearby sites, and inscriptions on ceramics.

As the researchers explain,

This was a time when the Chinese court encouraged private traders from China to travel abroad instead of relying on trade obtained through the tributary system. An earlier date range also would mean that the ship sailed closer to the fall of Srivijaya, one of Southeast Asia’s greatest maritime empires […] In addition, given this new data, we will have to re-evaluate the port where the ship was loaded and the vessel’s linkage with other major port cities along China’s central and southern coasts. The new results also may point the interpretation of the destination of the Java Sea ship in a new direction. It is now believed that further scholarly study of the cargo will lead to additional new perspectives.

However, some scholars are skeptical. For example, Dr. Michael Flecker, the maritime archaeologist who worked on the Java Sea Wreck, has expressed reservations: although the new research is persuasive, it is also a reminder that strong research (at least when it comes to ancient shipwrecks), can be inconclusive.

A miniature replica of the Java Sea Wreck, made by Nick Burningham. Source: Field Museum

This is undoubtedly an exciting new study, which clearly demonstrates the importance of using new and emerging technologies and research methods to revisit our understanding of Asia’s maritime histories.

But if we take a step back from the scholarly debates over comparative ceramic analysis and the pros and cons of different kinds of scientific techniques, this new report also serves as a reminder of the complexity of researching underwater cultural heritage, and of the need for a multi-disciplinary approach when it comes to contextualising ancient shipwrecks and their cargo.

In terms of the challenges we face in dating shipwrecks from Southeast Asia, there are of course the usual challenges of working with degraded organic materials and of how we account for discrepancies in dates and origins of these materials.

The main challenge, however, is getting access to this research material in the first place. We are incredibly fortunate that objects from the Java Sea wreck are in an institution, the Field Museum, and that this institution is in a position to enable further research on these objects. This outcome was not guaranteed, which makes it all the more remarkable. The objects could just as easily have been dispersed to auction houses and private collectors, or looted and sold on the black market. Indeed, the Java Sea Wreck had already been looted when Pacific Sea Resources first began work on the site in 1996.

To understand why this is the case, it is important to understand the regulatory context in which the Java Sea wreck was salvaged. Between 1989 and 2010 (when a moratorium on commercial salvage was introduced), the commercial salvage of shipwrecks was legal under Indonesian legislation. This placed Indonesia at odds with the international community, which introduced the UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage in 2001. This Convention preferences in situ preservation, and bans the commercial exploitation of underwater cultural heritage.

The Java Sea Wreck was commercially salvaged in 1996 by Pacific Sea Resources, which was awarded a salvage licence through Indonesian partner PT Sulung Segarajaya. Under the terms of the salvage licence, Pacific Sea Resources was entitled to 50 per cent of the objects or the proceeds of their sale. The Indonesian Government was entitled to the other 50 per cent. Despite efforts to sell the objects as a single collection, a buyer could not be found, and the cargo was subsequently split as per the original permit requirements. Pacific Sea Resources chose to donate their share to the Field Museum, while Indonesia sold its share of the objects.

This is a good example of the different outcomes possible under Indonesia’s ambiguous legislation relating to shipwrecks and their cargo. Indonesia’s legislation did not guarantee that objects would end up in a museum. Assemblages could be kept intact (like the Belitung wreck, now at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore and also the Intan wreck, in Jakarta’s Museum Seni Rupa dan Keramik) or they could be split up. If split up, the salvage company could donate their share (as with the Java Sea Wreck) or sell it to private collectors and auction houses. Critics are often quick to criticise commercial salvage companies for being no better than treasure hunters, but in the case of the Java Sea Wreck, the salvage company made the decision to donate the objects to a museum, thus ensuring they can continue to be studied. Were it not for this decision, we would not be having this discussion about the possible re-dating of the Java Sea Wreck.

The more common outcome for commercially salvaged shipwreck cargoes from Indonesia is for the objects to be dispersed on the market, usually piece by piece. This places an unfortunate emphasis on objects of financial value rather than allowing us to think about the assemblage in terms of its historical and archaeological value. Equally common is for objects to be looted from the site and sold on the black market for antiquities.

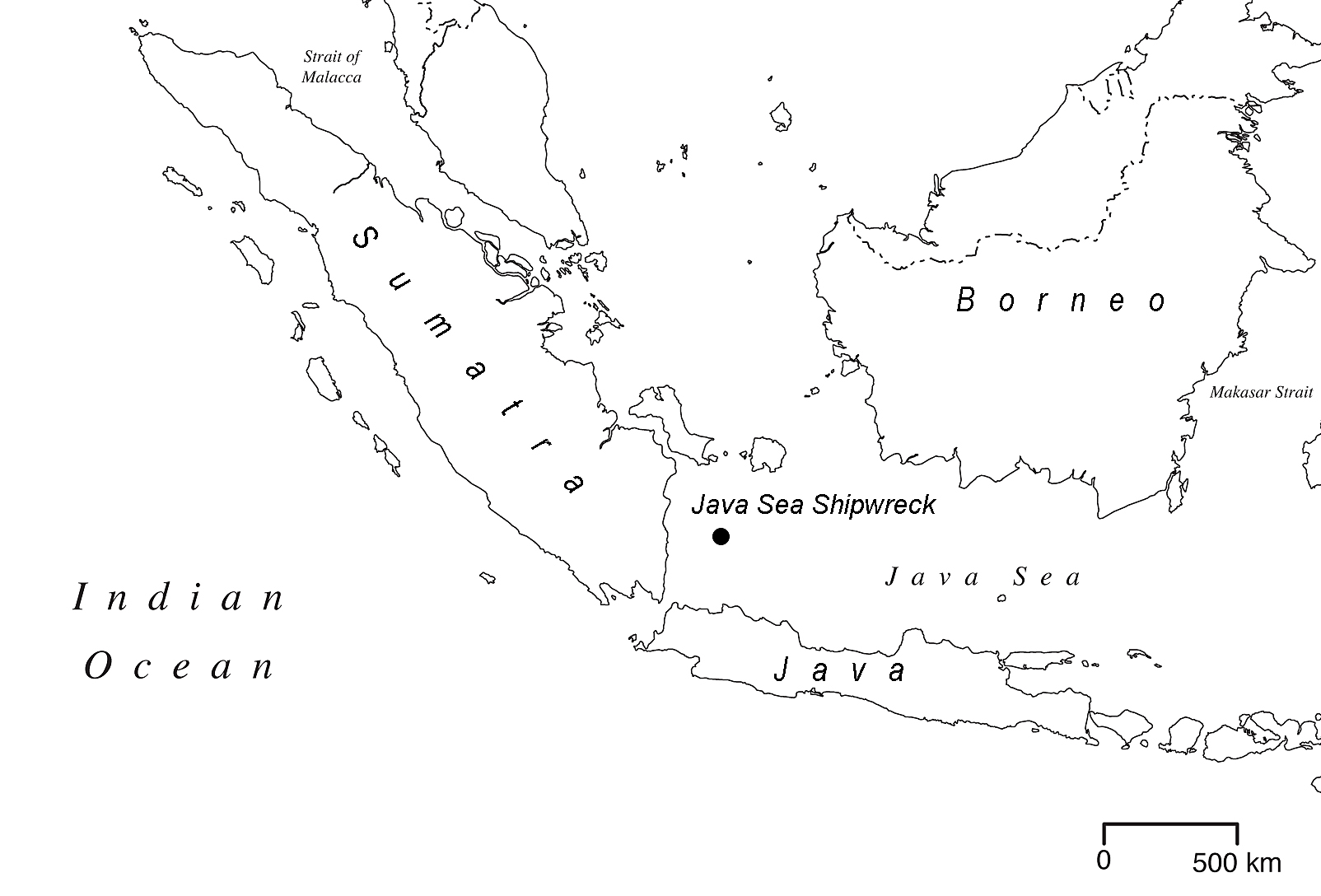

While it is wonderful that we are in a position to conduct new research, such as this study on the dating of the Java Sea Wreck, my concerns for the future relate to the fate of shipwrecks that are still in Indonesian waters. Indonesia has new legislation (Law No.11/2010) to legally protect underwater cultural heritage, and awareness is growing about the contribution maritime archaeology can make to protecting and preserving the country’s rich maritime pasts. But – as the recent destruction of WWII ships in the Java Sea demonstrates – Indonesia’s ability to physically protect wrecks remains limited. A glance at a map of the Indonesian archipelago – or a review of its complicated legislation relating to underwater cultural heritage – provides some indication of the challenges Indonesia faces in monitoring wrecks in its waters.

Location of the Java Sea Wreck. Source: Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association

The moratorium on commercial salvage brings Indonesia closer to the standards established by the international community. But there are many who believe that the ban has come at the expense of the very heritage it seeks to preserve and protect. This is because, in Indonesia, in situ wrecks have been proven to be vulnerable to destruction and damage. This has grave implications for other wrecks in Indonesia, and will negatively affect future research on the archipelago’s maritime histories. With this in mind, studies such as this one are even more valuable.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss