••••••••••

Editor’s note: this is an amended version of an article the authors originally published at ARC GIS Story Map

••••••••••

Indonesian Borneo has long been known for its gold mineral wealth—and its gold rushes. As Nancy Peluso has previously explored at New Mandala, not all of this gold mining occurs through large corporations or formal enterprises. In Central Kalimantan province, unlicensed and informal small-scale gold mining (in Indonesian, Pertambangan Emas Skala Kecil, or PESK) supports the livelihoods of thousands of artisanal and small-scale (ASM) miners and their families, while also creating transformative environmental impacts.

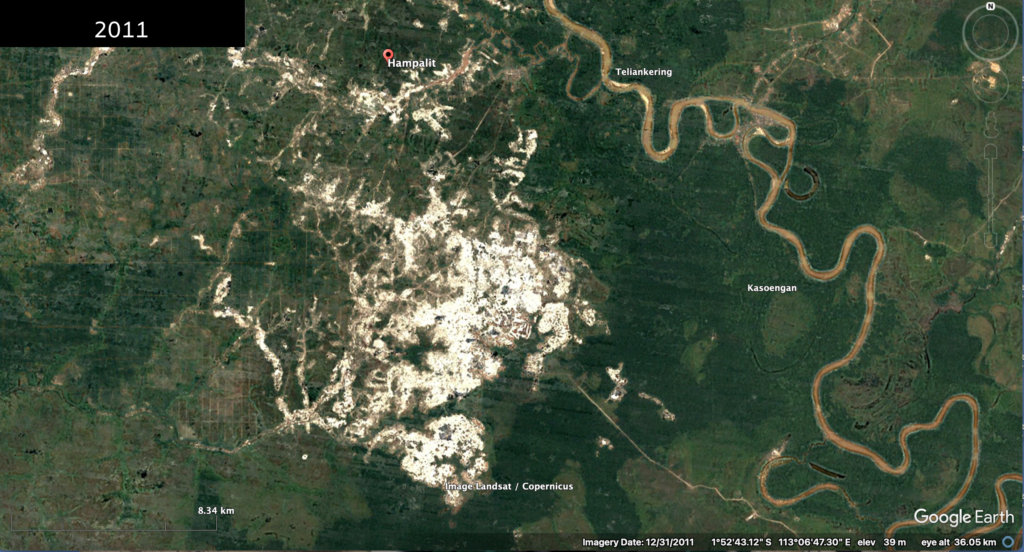

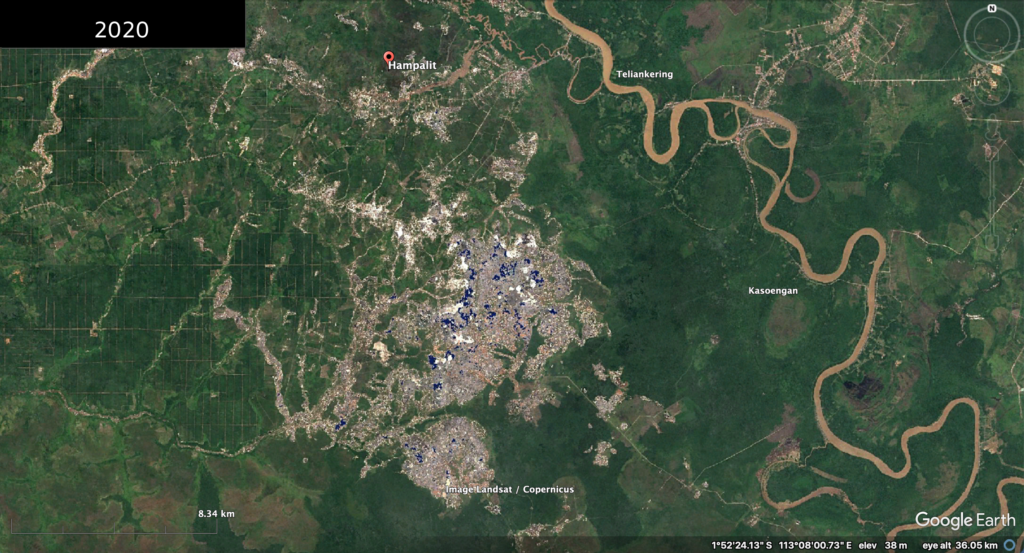

One of the most famous small-scale mining rushes in Central Kalimantan started in the late 1980s in Hampalit village, near the town of Kasongan, a couple of hours drive east of the provincial capital, Palangkaraya. Our collaborative research in Indonesia stretched across two Australian Research Council funded projects between 2016 and 2024, examining resource-based livelihoods and smallholder commodity production systems. The location of our fieldwork is shown in the blue circle).

The result of this boom was far from small-scale in scope and impact: at its peak during the Krismon or Asian Financial Crisis (c. 1997–99) a chaotic boom at Hampalit involved an estimated 10,000 ASM miners drawn from across Indonesia. The miners overtook a concession managed by an Australian-owned mining company, Hampalit Mas Perdhana, and began digging in the gold fields called Galangan. The landscape transformations over the past decades can be traced through Landsat/Copernicus satellite imagery hosted by Google Earth (see below).

In Indonesia such small-scale PESK mining rushes conjure ideas of the “Wild West” drawn from iconic American Western films. Mineral-rich territories become extractive frontiers with shifting claims to land and resources, where formal state authority is dissolved into complex alliances between landowners, small-scale miners, and machinery and petrol suppliers. Behind these actors are mining financiers up to the Dayak or Banjarese “big bosses” who operate in cahoots with sections of the local police and military. And then there are large ethnic Chinese Indonesian gold buyers, referred to as towkays. Sites like Hampalit are created through masculinist ideas of rugged miners taking high risks for high rewards, the proliferation of vice economies, the settling of disputes with violence, and huge environmental impacts.

Mining on land and river

Three decades after the initial rush during the Suharto era, today Hampalit remains a moonscape. The previous lush tropical peat forest is now the epitome of a ruptured landscape. While pockets of vegetation occur sporadically, there is an ugly beauty to this landscape, still nearly devoid of life, stretching beyond the horizon, a blister in the blazing tropical sun of Central Kalimantan.

While the boom years at Hampalit have long passed, the gold fields are not quite empty. Some of Kalimantan’s most precarious small-scale miners, arriving from places like East Java and Banjarmasin (the capital of neighbouring South Kalimantan province), still reside in this landscape, setting up in isolated shanties and spending their days working through the mine tailings for a second or third time.

These migrant miners use mobile engines known as dongfen after their Chinese manufacturer, placed on lanting platforms, excavating meters deep into the soil profile. The crews mine through the soil with hydraulic hoses, that slice and suck the slurry up to a kasbok (sluice), through a method they call tebang sapu (cut and sweep). Gold is then retrieved from carpets placed on sluices, albeit with a low recovery rate of only about 30%, with the remainder of the sediment spilling over into adjacent areas to the pit.

Miners take on significant safety risks, as unforeseen pit collapses can bury workers under tonnes of overburden, turning their workplaces into their grave sites. In December 2022, the pictured mining operation was producing 3-4 grams of gold per day, with 90 litres per day in fuel costs. Under a 50% profit-sharing scheme with the unit owner, five unit workers might each take home up to Rp200,000 per day (A$20). While this not quite a gold windfall, it is nevertheless double the going rate for construction labour back in Java.

Not all of Hampalit’s miners work in organised crews. On a visit in December 2022 we met “Agus” (a pseudonym)—a fiercely independent, disabled, miner and self-proclaimed online forest activist. After a divorce in Java, Agus landed a job in Bali, and then moved on to try his luck with mining in Central Kalimantan. For the previous four years, Agus had ventured each day to Hampalit on a modified 3-wheeled motorbike, sifting through the mine tailing sediment and collecting puya (a form of pay dirt), which he sells on to a local processor. Agus’ system is not mechanised, so while the volume of his puya production is low, he also avoids machinery and fuel costs, and can thus eke out a surplus.

Even in this most marginal of mining sites, Agus was not immune from paying “sitting fees” (uang duduk) to those who claimed to be the landowners, while facing petty extortion from the local constabulary. Agus survives through his force of will, and no small amount of pluck and guile: “it’s jungle law out here—everyone’s trying to make money!”, he exclaimed. We offered Agus a small sum of compensation for chatting with us under the hot sun, but he kindly refused, saying that he always supported himself. “No thanks. It’s not my mentality,” he asserted. While Agus’ situation is difficult, the ruined Hampalit landscape still offers Agus the right to an identity, and a livelihood, as an independent small-scale miner.

We learned the finer details of sampling, grading and identifying price points from a puya collector. Puya can contain traces of gold (retrieved through mercury) but the main focus is zircon sand (zirconium silicate), an element used in the production of ceramic tiles and other industrial materials. Bags of puya sell for between Rp6,000–12,000 per kilogram (A$0.60–$1.20), with so-called “red puya” fetching the upper bound). Puya is sent to Palangkaraya for semi-processing and is then exported to countries like China and India.

While Hampalit is the most famous land-based mining boom site in the area, it is far from a singular case. Another gold boom site has sprung up over the past two decades at the Sungai Sampang, along the eastern bank of the Katingan River. Down a tricky path of duckboards through the remote peatlands, one of our local PESK miner informants took us on a tour.

Boom mining sites can become quite established settlements, with their own daily rhythms and infrastructures. There are different ways of earning a living beyond mining—most of which involve separating miners from their gold and cash. While the peak of the boom has passed at the Sungai Sampang, different small shops offer machinery parts and repair, fuel, instant noodles, and of course hot coffee and cigarettes. Some warung shops with younger women double as karaoke–brothel–gambling dens in the evening.

In Sampang, we met one enterprising female duo accompanying their miner husbands who constructed a toll bridge over the swampy peatland track (right photo). While theft is always a danger on the mining sites, there is still a community here—even a local mosque. As our informant joked:

All of Indonesia is represented here: Javanese, Timorese, Batak, Banjar, Dayak. There used to be a lot more warung shops. It was lively (ramai).

The historical gold rush sites at Hampalit and the Sungai Sampang show different types of informal mining. Our next variation involves river-dredge mining. This involves larger floating barges (pontons), each fitted with a kasbok, and long sharpened pipes that can reach to the river bottom, using double Chinese-manufactured 20 and 30 horsepower engines with brands like “Sanghai” and “Yang Li”.

Ponton flotillas move down the great waterways of Central Kalimantan like the Katingan and Kahayan Rivers, the pipes puncturing the river bottom and sucking up the sediment with a terrific, deafening, smoke-belching din. Miners reported that in a good location, individual dredging crews of 3-6 miners have produced up to 100 grams of gold in one day (Rp123 million, or A$12,100 at current prices and exchange rates), although such jackpots are not the standard. As with land mining, profits are shared unevenly between the unit owner (50%) and the workers (10–20% each). The relative productivity of locations are assessed in terms of grams of gold per 200 litre drum of fuel.

Under the waters of the Katingan River, through a layer of white-blue clay, there is alluvial gold, washed down over the centuries from Gunung Mas, the gold mountain in the Heart of Borneo. (Photo: authors)

As with Hampalit, with river mining there are also contested property rights, uneven enforcement of state regulations, labour and safety issues, and deep environmental harms. On large rivers like the Katingan, miners need permission from village authorities to operate near settlements, although the liminal spaces between village boundaries provide grey areas for operation. Ponton owners must pay compensation to village authorities, and to adjacent landowners to mine in specific stretches (Dayak family claims to customary land are often narrow strips of territory running perpendicular to the river). Significant community tensions can result between those community members who accept or resist such river mining, and negotiations can include intimidation by river miners and their bosses.

Unlike the nearly open access arrangements at Hampalit, it is mostly Dayaks from around Katingan Regency who control river mining. Some assert this is because “Javanese can’t swim”. But mining for gold on the major rivers is also more lucrative and is thus kept more under the control of local Dayak groups. This extraction produces drastic changes in river’s geomorphology and ecology, rendering the river unnavigable in places due to the accretion of new sand bars, and surely with major impacts for fish and other aquatic species.

Mercury, used to capture and amalgamate fine grains of alluvial gold, escapes into the environment. However mercury is also expensive, and miners are aware of its toxicity, so it is not handled carelessly. (Photo: authors)

Bosses and buy-offs

Overall, state authority is present, but highly compromised with what the state calls “PETI”—Penambangan Tanpa Izin or “illegal mining”. The political economy of police “crackdowns” involves an intricate interplay between actors. Outside of periodic police patrols timed for the arrival of a new government administration, or the annual Indonesian Independence Day holidays in August, major crackdowns depend on provincial or federal funding from Jakarta. Word then inevitably leaks out from the district level that a major crackdown is imminent. Miners move their river pontons in to shore for a few weeks of rest and relaxation and hide their lantings and hexa excavators in the forest. If police patrols do show up unannounced, payments of 500,000 to Rp1 million and an offering of cigarettes might be in order.

Behind the scenes, miners’ groups, and larger mining bosses, have already made their contributions to the local constabulary. In actual event, a few unlucky miners with contraband gold or mercury in their possession might be arrested, although jail sentences of up to a year have also been handed out (attracting vociferous protests from the local PESK mining community). As one of our informants related: “Mining is like a grapevine, or a tall tree. Information trickles through the system.” We asked him whether he was nevertheless concerned about police crackdowns. “Of course!”, he replied:

What I am doing is illegal! With the police, today we give them food. But tomorrow they can eat us (Kalau polisi hari ini bisa kita kasih makan, besok bisa makan kami).

The system of access to subsidised diesel fuel (solar) is another area of collaboration between mining bosses and local police units, through the “fuel mafia”. In Indonesia, petrol and diesel fuel for public consumers is heavily subsidised to a level about 30% beneath the market price. Obviously subsidised solar is not supposed to be used for informal PESK mining. However mining bosses, in negotiation with police, facilitate pelansirs (illegal fuel distributors) driving modified vehicles to stock up on cheap fuel at local petrol stations and distribute it on to their miners.

Thus, to become a top big boss in Central Kalimantan PETI mining, one needs upfront capital for purchasing mining equipment (including illegal mercury), for fending off crackdowns, and for securing access to subsidised fuel—all of which require productive relationships with the police.

Bosses also play a critical role in provisioning the required venture capital for organised PESK mining. “Big bosses” can manage numerous mining units. If one wants to be a river mining unit owner but lacks sufficient capital (typically now Rp80 million or A$8,00), a big boss (mostly local ethnic Dayak) will advance Rp50 million rupiah in financing and machinery under a profit-sharing arrangement. The aspiring unit owner then up-fronts the remaining Rp30 million to the joint venture, under the agreement that all supplies and fuel will be purchased through the boss.

Since mining is by nature unpredictable, if a unit is unproductive, the boss will write down or write off the loan. In interviews we asked why workers and unit owners do not seek to under-claim their actual gold production, or find other ways to skirt around their bosses. As one miner told us:

It’s not so easy to lie. Or rather, it’s easy to lie, but it will be just for one time. The boss has many eyes. (Interview, September 2016).

Independent unit owners in the Kelanaman

Not all PESK mining in Katingan Regency is controlled by bosses. In mining sites at the river–forest frontier of the Kalanaman River (a tributary of the Katingan), outside of the State Forest zone, local Dayak community members mine for gold and puya, using various techniques based on smaller lanting platforms and machines. Here, any youngish male Dayak villager with sufficient mining nous, start-up capital of about Rp30 million rupiah, A$3,00), and charismatic managerial prowess, can assemble a team and make the leap to being an “independent unit owner”.

The risk of being an independent unit owner is high, as any losses must be fully borne by the owner—but so are the rewards. If an independent unit owner (taking a 50% share of profits) works with a crew of 4 others (each allocated a 10% share), the owner takes 60% of total earnings. If this risk is considered too high, a villager can also focus on mining with smaller equipment for puya pay dirt, which provides a lower but a steadier income.

Below: upriver mining at the Kelanaman River, showing the effects of dredging (video by authors)

The Ngaju Dayak community miners at the Kelanaman River work with stronger social protections than elsewhere, as they are often accompanied by family members, and work with village peers. Wives and small children camp for weeks at a time with the miners at site, which enables low-cost cooked meals and childcare (while also allowing womenfolk to keep a good eye on their husbands).

In our Katingan research village of Tumbang Jukung (a pseudonym), 14 out of 25 households we surveyed said they had at least one family member working as a miner at the Kalanaman River, either as worker or unit owner. Their earnings accounted for 44% of average income in surveyed households. While environmental impacts were widely acknowledged (by 14/25 households), most did not object as the mining site was judged a safe distance (about 10km) from their village housing area.

In 2024 Tumbang Jukung did however successfully resist, and evict, a flotilla of ponton miners from dredging their village riverfront, and they have also protected a village local oxbow lake, which is a critical source of fresh fish, from the threat of mining. Thus, Dayak community members do uphold a partial conservation ethos, even as they recognise the environmental damage caused by PESK mining, while weighing that against the imperative to earn a living.

Ghosts in the machine

An in-depth investigation into the land deals behind the downfall of one of Indonesia's most senior judges.

Here, PESK mining permits Dayak communities an independent livelihood on their own land—far preferable to most than corporate oil palm plantation labour. Mining generates steady returns, with the revenues circulating within the community. And the village miners are even home for dinner.

The gold shops in Kereng Pangi

What happens to the gold from Katingan Regency? There are scattered gold shops (Toko Emas) throughout the district and the provincial capital, and some even at mining sites. However, Kereng Pangi town is a key gold centre, with about 20 gold shops running down one street. These are mostly managed by people from Banjarmasin and are backed by Banjarese or Javanese bosses. The shop owners will accept a miner’s gold–mercury amalgam and burn off the mercury into a fume hood, which captures and recycles some of the mercury. The remaining gold concentrate is 90–96% pure, with the gold shop owners using something of an art to assessing this (based on knowledge its origin of location, and the structure, colour, density, and weight of the gold, informed by previous tests).

During our visit, the typical gold price paid to miners was Rp1.23 million (A$120) per gram. Shop owners receive daily price updates at 11am from their bosses. The gold shop bosses handle monthly payments to the police of Rp3.8 million (A$380) per shop, suggesting annual payments of almost A$90,000 from this street in Kereng Pangi. Our interviewees reported that an average shop might purchase from 100–500 grams per day, from a regular clientele of 50 to 200 mining groups (averaging 4 workers per unit). Using the low-end numbers of 100 grams of gold purchased per day per shop, and assuming 20 shops operating 300 days per year, we can make some conservative back-of-the-envelope calculations: at least 600 kg of gold purchased annually on this golden street of Kereng Pangi town, worth nearly Rp740 billion (A$73 million), involving at least 4,000 miners.

At Kereng Pangi, the collected gold is poured into 1kg blocks and transported by motor vehicle to South Kalimantan. There, an ethnic Chinese towkay in Banjarmasin reportedly refines the gold into 99.9% pure bars. At some nebulous point, “illegal” gold from Katingan Regency enters the legal market, and is likely sold onwards to domestic goldsmiths, to international gold markets, or perhaps even the Indonesian central bank.

With real gold prices near century all-time highs (see below), all incentives are aligned for ASM mining to continue in Kalimantan and Katingan Regency.

The end game

During our research, we often discussed, “what’s the end game for PESK–ASM mining in Kalimantan?” Our fieldwork demonstrates the diversity of mining locations and practices, and the complex social, political and economic relations that go into its production. While our informants (and local graffiti taggers) often joke that a certain boom mining site was “like Texas”, in fact the gold commodity chain we trace above is highly geographically specific.

While some boom sites take on a freewheeling sensibility, other sites are more firmly controlled by local community members. And far from being immune to government regulation, informal mining operations occurs in close juxtaposition with local state authority. Many local officials are thoroughly enmeshed in this “illegal” system. Recent upward moves in global gold prices are intensifying extraction pressures, although shop owners also note that the volume of their purchases are below the peak, suggesting there may be some limits to new boom locations in Katingan.

While thousands of Dayaks and migrants forge an independent livelihood, and an identity, as small-scale miners, the clear and pressing problem is that entire peat forest landscapes can undergo literal upheaval, and aquatic environments face more or less complete destruction—for centuries into the future—for their hidden small grains of gold. And in the rivers, streams and forests of Katingan Regency, the gold lies nearly everywhere.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss