A helpful diagram of the ‘fat’ Prabowo-Hatta coalition versus the ‘slim’ alliance backing Jokowi-JK (source: detik.com)

The presidential tickets for the upcoming election have been finalised, and with only two sets of candidates standing, a single-round showdown is now certain. For all intents and purposes, the presidential campaign commenced on Monday 19 May, with vice-presidential candidates announced to run alongside Joko Widodo of PDIP and Prabowo Subianto of Gerindra, and their nominating coalitions finalised. For the record, on 9 July, Prabowo and National Mandate Party (PAN) chairperson Hatta Rajasa (Prabowo-Hatta) will be pitted against Jokowi and former vice-president Jusuf Kalla (Jokowi-JK). The vice-presidential nominations resulted from weeks of wrangling, with Hatta initially hoping to run alongside Jokowi, and Jokowi prevaricating over several alternatives to Kalla (the preferred choice of PDIP chairperson Megawati Sukarnoputri).

However, a more interesting facet of the pre-declaration negotiations relates to the political coalitions established in support of the two candidate pairs. As the candidates and their coalition backers effectively launched their election bids, before a television audience of millions, the contrast between these two campaigns was, in Indonesian terms, quite remarkable. I will run over some of the more interesting elements of the last several weeks of inter- and intra-party bargaining, with an eye to the ideological positioning resulting from the coalition formation process, and try to ascertain what these developments could mean for the coming campaign.

Prabowo Subianto and Hatta Rajasa alongside their political allies – among them Aburizal Bakrie, Amien Rais, Anis Matta, and Suryadharma Ali, at the Indonesian Electoral Commission office in Jakarta [source: TribunNews].

Surprisingly, two of the 12 parties to contest the national elections are not part of either nominating coalition: SBY–who appears wary of a Prabowo presidency and enjoys a frosty relationship with Megawati–has declared that his Democrat Party (PD) will not (yet) align with either camp, despite his status as Hatta’s in-law. Meanwhile, the Indonesian Justice and Unity Party (PKPI)–which won less than 1% of the national vote–was ignored by PDIP when it sought to support Jokowi.

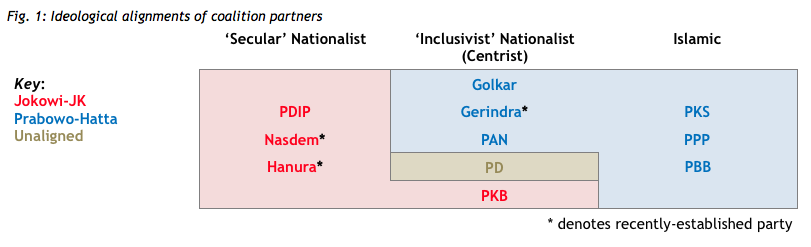

Revealingly, particularly given the prevalence of scholarly discourse which downplays the role of ideology in Indonesian politics, the nominating coalitions have formed, to some extent, along ideological lines. Ideological and cultural ‘cleavages’–once treated as the primary analytical lens for the study of Indonesian party politics–no doubt diminished during the New Order, and their academic utility has faced widespread scepticism since that regime’s collapse. However, the coalitions ahead of this year’s presidential election, which have arisen through an organic process of negotiation and contestation, are in fact quite ideologically defined.

It is useful here to review the ideological spectrum typically applied to Indonesian politics, which places parties along a continuum from the ‘secular-nationalist’ PDIP–which has championed the separation of religion and state–to the pseudo-Islamist parties (PKS, PPP, PBB) which favour an enhanced role for Islam in governmental and policymaking processes. The parties which occupy the centre of this spectrum–categorised as “inclusivist” by political scholar and recent presidential hopeful Anies Baswedan–include Golkar, PD, PKB and PAN. These parties are all ‘Pancasila-ist’ according to their party statutes, but have been comparatively willing to compromise on Islam-inspired political agendas (PD and Golkar), or maintain constituent ties to Islamic mass organisations (PKB and PAN).

The more recently-established Gerindra, Hanura and Nasdem–lacking well-established parliamentary track records–are not easily incorporated into this schema. All were founded on pro-Pancasila platforms and boast sizeable non-Muslim memberships (indeed, Hanura was the only party to propose a non-Muslim presidential or vice-presidential candidate during the legislative campaign). While none directly promote Islamic agendas within their statutes, a clause within the Gerindra party manifesto which purports to ‘protect religious purity’ (‘menjaga kemurnian agama’) has been interpreted as over-reaching into religious affairs, and even threatening the religious freedoms of minority groups such as Shia and Ahmadiyah (a frequent criticism of the Yudhoyono government relates to its failure to protect such groups from persecution). Coupled with Prabowo’s willingness to adopt a more ‘Islamic’ tone in his campaign (discussed below) it seems there is sufficient evidence to doubt Gerindra’s commitment to a ‘secular’ agenda. For these reasons, Gerindra cannot be included in the ‘secular-nationalist’ camp.

The coalitions

Following several weeks of coalition talks and speculation over vice-presidential nominations, as well as the late withdrawal of Golkar’s unpopular chairman Aburizal Bakrie from the race, four parties are supporting Jokowi-JK, while six are backing Prabowo-Hatta. The Jokowi-JK bid is being led by PDIP, alongside Nasdem, PKB and Hanura. Prabowo and Hatta have the support of their respective parties, Gerindra and PAN, as well as the three most staunchly Islamic parties: PKS, PPP and PBB. Golkar was a last-minute addition to the Prabowo-Hatta coalition, though it would seem this arrangement eventuated only after the failure of Bakrie’s efforts to horse-trade for personal concessions from Megawati (and a generous offer from Prabowo). Arguably, the formal omission of Golkar from the PDIP-led alliance may better position Jokowi-JK to lead a more pluralist, religiously moderate government as forecast some weeks ago by Dominic Berger here at New Mandala. But at this stage, it is clear that the weeks of political manoeuvring have resulted in a plainly polarised pair of coalitions: an ostensibly pluralist alliance backing Jokowi-JK, and a Prabowo-Hatta coalition possessing a far more obvious ‘Islamic’ character.

The alignment of PDIP with the Nahdlatul Ulama-oriented PKB can be seen as consistent with those parties’ shared roots in Java and the legacy of post-independence coalitions between NU and Sukarno’s PNI, while the relatively tolerant theological outlook of NU is broadly compatible with the pluralist PDIP. Although NU chairman Said Agil Siradj has pledged his personal support to Prabowo, PKB was relatively successful in augmenting its ties to the mass organisation ahead of the legislative elections, and the organisation’s membership has voted independently at past presidential ballots. Similarly, the common strength of Golkar and PAN in Indonesia’s ‘outer islands’ may suggest an added layer of compatibility to their union. Of course, it is notoriously risky to draw meaningful parallels between voter behaviour at Indonesia’s legislative and executive ballots. Exit polling at the legislative election showed varying degrees of correlation between constituents’ party and presidential preferences. However, it is worth noting that, based on Indikator’s exit poll, of the parties which do not have a politician engaged in the presidential race, only Golkar and PBB ultimately supported the candidate less favoured by their average voter.

Fig. 2: Favoured presidential candidate, by party choice at legislative election [source: Indikator]

While the coalitions themselves seem relatively ideologically consistent, the fact that parties like PAN, PKS and the Masyumi-inspired micro-party PBB have thrown their support behind a notorious New Order figure such as Prabowo could–taken at face value–cast doubt on this coherence. However, rather than dismissing such an alliance as indicative of ‘promiscuous power-sharing’, it must be considered in light of the institutional constraints on presidential nominations, the limited coalition alternatives available to these Islamic parties, and the respective ideological orientations of Gerindra and PDIP. While the former is a highly personalised vehicle for Prabowo’s presidential ambitions, and is therefore beholden to his own political leanings, PDIP has longstanding ideological and socio-cultural traditions underpinning its political alignment. As a member of the military’s Islamic faction during the late New Order, Prabowo’s own ability to play up his religious credentials must also be taken into account. To be sure, there is something quite surreal in Prabowo’s lauding of Amien Rais as “the father of reformasi”, sixteen years after the then-Kostrad commander’s subordinate, Kivlan Zen, allegedly threatened to shoot the PAN founder. However, Prabowo has long displayed a chameleon-like ability to variously foreground his nationalist, religious, cosmopolitan or commercial credentials where appropriate. Having spent months wooing foreign investors and the international commentariat prior to election season, he has since adopted a populist, ultra-nationalist rhetoric which he believes will improve his domestic traction. When working with his new coalition allies, he will doubtless emphasise his status as a Muslim.

Prabowo himself will know that the heavily Islamic overtones which dominated the Prabowo-Hatta declaration could alienate non-Muslim or non-practicing Muslim voters, and his desire to praise the “nationalist” credentials of figures like PKS patriarch Hilmi Aminuddin and PPP chairman Suryadharma Ali probably indicate that he wants to maintain, as much as is possible, a broad-based populist image. Among the more memorable lines in another impressively impassioned piece of Prabowo oratory was his characterisation of his supporting coalition as comprising “religious parties and nationalist parties, though within those nationalist parties we find religiosity, and within those religious parties we find nationalism.” Prabowo may try to isolate his personal image from that of his coalition partners, but if the nominating parties continue to play a significant role at Prabowo-Hatta campaign events, we can expect to hear a good deal more recitation of Qur’anic verses from the Muslim politicians (including Hatta), and loudly-vocalised takbir during the candidates’ speeches.

While it is not clear that Prabowo pushed to establish an Islam-oriented coalition, it is notable that PKS, PPP and PBB supported his candidacy against a backdrop of ‘black campaigns’ querying Jokowi’s religious beliefs and political independence (i.e., the notorious ‘puppet president’ [‘capres boneka’] label). It is worth recalling that the only major union of Islamic parties since democratisation–the short-lived ‘Poros Tengah’ of 1999–was established to deny Megawati the presidency. Fifteen years later, and notwithstanding internal wrangling in PPP over the ultimate direction of its support, it would appear that parties like PPP and PKS still naturally align against the secular, pluralist values represented by PDIP and its cadre. It is also noteworthy that only Gerindra, PKS, PPP and PBB voters generally favoured a candidate other than Jokowi according to exit polls conducted at the legislative ballot.

The PDIP-led declaration of the Jokowi-JK ticket contrasted sharply with the heavily religious tone of the corresponding Prabowo-Hatta event. Popular PDIP politician and event emcee Rieke Diah Pitaloka (dressed in tight red trousers and a ‘Jokowi for President’ baseball cap) seemed genuinely surprised when the call to prayer interrupted her animated interactions with a sizeable crowd outside Gedung Joang 45 in Jakarta. The Christian Papuan musician and PDIP member Edo Kondologit performed a series of nationalist songs. There was little religiosity on display, and the climax of the ceremony featured Jokowi and Kalla kissing the national flag. While Jokowi has sought to augment his Islamic credentials with plenty of photo ops at mosques on the campaign trail, there can be no question that he represents the pluralist presidential alternative: a status very much consistent with his position as a PDI-P protegée. It is worth noting that Iriana Joko Widodo–unusually for the wife of a prominent contemporary politician–has steadfastly refused to don a headscarf. One reason for the selection of Kalla as Jokowi’s running-mate is his perceived capacity to reassure Muslim voters, a portion of whom apparently remain unconvinced of the Jakarta governor’s responsiveness to their constituencies.

Joko Widodo, Iriana Joko Widodo, Mufidah Kalla and Jusuf Kalla at Gedung Joang 45, Jakarta, Monday [source: suara.com]

Although pragmatic, power-oriented calculations played a significant role in the presidential coalition-formation process, the alliances now drawn up have also been informed by ideological considerations, which were clearly reflected in the contrasting conduct of their candidate declaration events. Much now depends on how effectively the party vehicles can be harnessed in support of their chosen presidential hopefuls, and how successfully the candidates can spruik their platforms and personal appeal. As things stand, Prabowo is comfortably out-performing Jokowi on this front. While Jokowi has struggled to inject energy, enthusiasm and substance into his formal public appearances, Prabowo remains a highly effective campaigner on his chosen platform: ultra-nationalism and pro-poor populism, now coloured by religious overtones. While Amien Rais compared Prabowo’s oratory (and, less convincingly, his appearance) to that of Sukarno during the Prabowo-Hatta declaration, Jokowi’s tweet-length speech at Gedung Joang 45 confirmed his documented reluctance to make meaningful public statements which articulate a clear vision for the next five years.

This discrepancy in the management of the two campaigns is partly related to the candidates’ respective positions within their party machines. Whereas Prabowo has personal control over Gerindra’s slick political vehicle, Megawati retains ultimate authority in the more factional PDIP–a fact illustrated by the appointment of Kalla as Jokowi’s running-mate, despite the latter’s preference for Corruption Eradication Commission chief Abraham Samad. However, it is incumbent upon Jokowi himself to make use of the numerous ‘teams’ dedicated to his campaign effort. With an ideologically distinct and streamlined coalition behind him, Jokowi would be well-served embracing his pluralist and reformist credentials and turning his attention from internal battles to the business of the presidential campaign.

Prabowo, meanwhile, is gathering support from disaffected elements previously close to PDIP’s coalition partners. The PKB-affiliated presidential hopefuls, former Constitutional Court Chief Justice Mahfud MD and ‘Dangdut King’ Rhoma Irama, as well as the Christian ethnic chinese media tycoon and recent Hanura vice-presidential nominee Hary Tanoesoedibjo, have now declared for Prabowo-Hatta. However, typical of the sort of fragmentation and fluidity which characterises Indonesian politics, elements within Golkar have moved to support Jokowi-JK. Kalla’s status as the former Golkar chairman gives the ‘natural government party’ a foot in both camps, probably allowing it to align with whichever side prevails in the presidential ballot. Kalla is also a significantly more popular figure than Hatta, and many within the Jokowi camp will hope that the ‘JK effect’ can help reinvigorate a flagging campaign.

These political manoeuvres should not distract from the obviously ideological outcome of the 2014 presidential coalition formation process. The choice for Indonesian voters is quite clearly between a belligerent nationalist rhetorician backed by Indonesia’s more conservative political elements, and a low-key would-be reformer, supported by a fundamentally pluralist coalition, whose campaign continues to tread water. Whatever the outcome, the coming weeks are sure to make for fascinating viewing.

……………

Tom Power is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss