In Durban, South Africa at the UN-organised World Conference Against Racism, in September 2001, the Malaysian foreign minister made a plea during the plenary session that the countries present respect the rights of migrant workers. It was a speech that in many ways emphasised the extent to which migrant workers are invisible in Malaysia. The minister never considered if, or how, the speech could be applied in Malaysia. The migrant workers he pictured were the educated Malaysians working in the West, not the millions who have built Malaysia’s skyscrapers, brought up the country’s children, cleaned the toilets and swept the streets. It is against this background, where the migrant workers of Malaysia do not exist (until today) in the country’s political landscape, except as a scapegoat for rising crime and an outlet for xenophobia, that the importance of Irene Fernandez is thrown into relief.

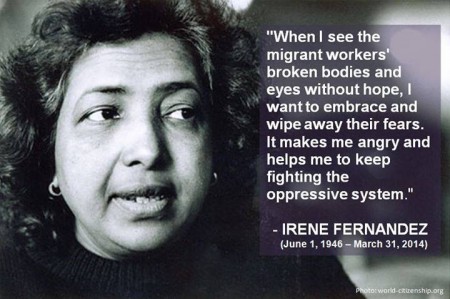

While Fernandez has been a champion of women’s rights, labour rights and political reformation generally, it was her work in the arena of migrant workers’ rights, both locally and regionally, that brought her international renown. In 1995, she held an explosive press conference. Having spoken to over 300 migrant workers who had been detained in immigration camps, she released a report detailing abuse ranging from sexualised harassment and humiliation to deaths in custody. As yet, there has been no systematic investigation into the conditions in detention camps. However, in March 1996, the Malaysian government kicked off what is believed to be the country’s longest-running criminal trial. Charging her with publishing false information, the Government deported key witnesses – primarily migrant workers – and kept the prospect of a prison sentence hanging over Fernandez’s head for over a decade, until her final acquittal in 2008.

Not once during that time did her commitment to the fight for workers’ rights abate. At the conference in Durban, she showed a video documenting the fight for a workers’ family to learn why he returned home in a casket. She spoke about the conditions facing migrant workers’ in Malaysia, the abuses by ‘agents’ eager to exploit their client’s eagerness to find a way out of poverty. Desperate, they would sell everything they owned to cover the agents’ fees, confident in the promise of a better life, promises rarely fulfilled.

The life of Irene Fernandez holds some important messages not just for her fellow Malaysians, but messages that resonate in Australia, as we continue to debate on whether offshore detention is humane and necessary. These are just some of the messages, the lessons she taught me, through both her work and her example.

The first message is to see people. There are people in every society that are invisible – living in Melbourne, I’m amazed how frequently I’m told that there are no indigenous people living here. The issues of indigenous Australia lie ‘elsewhere’, to the north, to the west. I often see Australians (not all, not homogeneous) render invisible everyday racism, sexism and hostility to those who are marginalised, often under the guise of humour.

The second message she taught me is that economic migration is not just understandable, but sometimes just as much a fleeing from terror as those we consider ‘legitimate’ refugees. The people who are battered and bashed by market forces can also face dehumanising conditions, face death, torture and starvation. If we are serious, and I have grave doubts whether Australians or the international community in general is serious, about respecting the dignity and inherent worth of every human being, we need to recognise and aggressively address the fact that poverty undermines humanity at least as much as tyrannical governments do.

The third is that work that is done not for praise or gratitude. While she was the recipient of various prestigious human rights awards, there are very few of the migrant workers in Malaysia who would be able to tell you about Irene Fernandez, her life and struggle. But neither the accolades of the international human rights community or the lack of renown at the level of migrant worker bothered her. I don’t believe that she struggled for them, but for herself and for those of us who walk past these workers every day. Her work was rooted in her faith, she lived as a staunch Catholic, but it was not bounded by it. She recognised that our humanity is defined by the manner in which we relate to others, by those whom society considers the least and her life was defined by what she could do to rectify the social ills she saw undermining society, in Malaysia, in ASEAN and across the globe.

Irene Fernandez, Executive Director of Tenaganita, passed away on 25 March 2014 due to heart failure at the age of 67.

Sonia Randhawa is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne, studying the role of women journalists in the Malay-language newspapers. She is also a director of the Centre for Independent Journalism, Malaysia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss