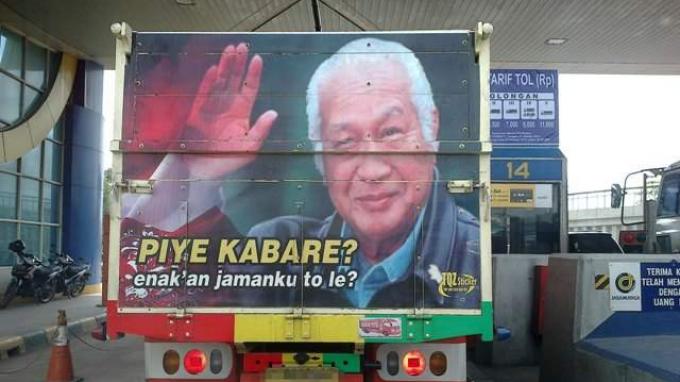

Nostalgia for Suharto is an ever-present annoyance in contemporary Indonesia. The rhetorical basis of this nostalgia is a whitewashed caricature of his military-dominated regime: that it provided a stable political environment and prosperity for ordinary people. These claims are difficult to defend historically, and despite the present nostalgia, few people actually believed this rhetoric at the time.

Take a look at this video in Indonesian from a YouTube account dedicated to Suharto nostalgia. It shows the president in his front yard, speaking with children. In celebration of National Children’s Day in 1994, a selection of primary school students from across Indonesia, all around twelve years old, are allowed to ask the president some questions. The presence of Western onlookers suggests that Suharto intends for the event to be a spectacle of his achievements for an international audience.

What he gets instead is an informed and piercing questioning of his three-decade reign, delivered by the children in polite but direct language. They repeatedly hone in on two themes: the inequality of opportunity they experience, and the autocracy of Suharto’s leadership. His conversation with the children demonstrates that the flaws of his regime were obvious, even to people whose entire education had taken place in state schools teaching the state ideology.

“How’s it going? Wasn’t it nicer back in my day, son?” Many people suspect that these nostalgic images are not spontaneous political expressions by truck drivers, but sponsored by conservative political parties. Source: Tribun News (Ind.)

Inequality of Opportunity

The children show great concern for the disadvantaged and repeatedly ask Suharto about opportunities for the less well-off. One of them asks “Can disabled people become doctors?”, and the president answers that the only thing that matters is having the determination and enthusiasm to study and succeed, and therefore to serve the nation. He responds in a similar way to a question about how children should stay healthy: “Listen to your parents, eat properly and don’t indulge in what they forbid. If you become sick, listen to the experts and clinicians”.

Whenever the children ask about the social circumstances of disadvantage, Suharto shifts the focus to the individual’s behaviour. He articulates the right-wing assumption that the playing field is basically level and that inequality of outcome is largely the result of personal character: the extent to which you obey wise authority, work hard, and are motivated to serve the nation-state.

His questioners don’t buy this argument. A girl asks “Can a woman become president…” and continues (after he interrupts her with a dismissive “yes, yes, of course”) with the real point of her question: “… and where must she go to school?”. The audience laughs, perhaps to diffuse the directness of the girl’s challenge to the assumption of equal opportunity. It seems to catch the president off guard and he becomes obstinate, “Yes, it’s just the same, the same conditions, no matter what”. Despite their politeness, the children seem unconvinced by Suharto’s explanations for the social injustices they experience.

One-Man Rule

A few of the children tell Suharto that they want to grow up to be president, and his responses demonstrate the peculiar way he views that office. He describes the presidency not as a service to his citizens, but as a prize that “190 million people have to fight over”. For him, collegial leadership is impossible: “If there were more than one, with many captains, the state would be ruined.”

There’s a linguistic trick happening here: the children ask him why there can only be one president, i.e. “Why doesn’t anybody except Suharto get to be the president?”, but he interprets the question to mean “Why aren’t there multiple presidents at the same time?”. In response, he uses the traditional analogy of state leadership as nuclear family: “It’s just like at home, right? There’s no two or three fathers, the one who runs your household is only one father”.

After a few more questions in this vein, Suharto starts to use some buzzwords related to constitutional democracy, but in a strange way. He describes the power of the president: “he is bound, by the broad outlines of the state, by Pancasila, by the 1945 Constitution”, as if the structures of the state are constraints on the president’s personal power, rather than the presidency being an office created by and subordinate to the state.

Soeharto in Indonesian Short Stories (Ind.) This book cover illustrates Suharto’s deep attachment to the symbols and trappings of Javanese kings.

He then mentions the five-year term of office as another constraint: “After five years, he may be picked again, for another five years, and then picked again, for another five years, and so on”. The implication is that the only possible outcome is for the same person to be re-elected again and again. The children keep returning to this question because they are well aware that the presidency should be a public office, not an honorary title for a de facto king.

As the questions continue, the king smiles but is not happy. The atmosphere becomes tense as he snaps back at the children: “Why are you asking these questions? Who put you up to it?”. Even the nostalgic YouTube commenters pick up on the tone: “Skip to 7:26,” they say. “It’s sinister.”

Conclusion

Many of the children who spoke to Suharto that day would have been finishing school when he was toppled in 1998. Their skepticism remains necessary, especially now that a significant proportion of young Indonesians don’t know about the dictatorship except from history books. New Order narratives retain their hold on the country, especially on its political and business elite, and can be easily turned to the service of a regressive and authoritarian agenda. What this conversation with Suharto shows is that those narratives were never credible in the first place, even to the poster children of the regime.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss