As with rice, Indonesia experiences high sugar prices. Domestic sugar prices can be three times the average international price. Near the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak last year, sugar prices rose a further 25 percent in some areas. Consumer sugar prices differ substantially between different regions, but even seemingly low prices are still high compared internationally. These inflated prices make for big profit margins, especially for importers. Indonesia imports over two thirds of its sugar. Although there are anti-sugar import protests, they do not produce the same sort of sensationalised outrage associated with rice imports.

Calls to reform Indonesia’s sugar trade often appear in media. Proponents for lowering prices on behalf of consumers and commercial users blame the government’s opaque import licensing and quota system for creating an uncompetitive sugar market. They claim allowing greater quantities of imported sugar does not lower prices as just a few groups have permission to import. Their efforts to reform the import license and quota system to lower sugar prices for consumers have little influence because those who profit from how things work now have few reasons to accept change.

Indonesia’s own sugar farmers and millers, represented by assertive and politically connected lobbying associations, want to preserve already high prices. So too do select bureaucrats, politicians, conglomerates, and their oligarchs, as well as state-owned enterprises that make windfalls from the structure of the existing sugar market. But perhaps less obviously, Indonesia’s security institutions benefit from sugar capital. They have profited from sugar since the birth of the Republic. Addressing high sugar prices requires addressing the sensitive issue of reforming security force financing practices that have been institutionalised since decolonisation. If modes of sugar patronage institutionalised in tumultuous periods of Indonesian history remain unaddressed, incremental changes to sugar-related regulations can only have a piecemeal effect on prices.

The roots of sugar capital

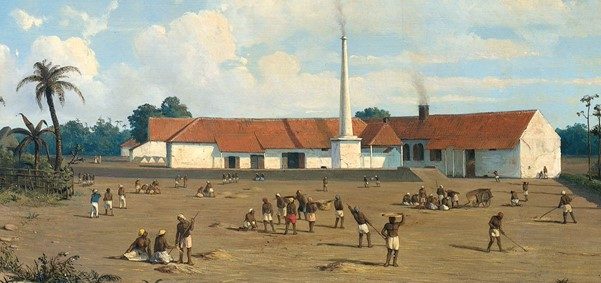

Enclaves of sugar production and processing fuelled the early colonial state’s capitalist development. Sugar production enabled the emergence of private Chinese and European entrepreneurs on Java, some of whom went onto become the entire region’s wealthiest oligarchs. Given sugar’s high value, the Dutch forced its production among other cash crops in the Culture System (Cultuurstelsel, 1830-1870). Before the Great Depression, Java was consistently the world’s second largest sugarcane producer and exporter after Cuba.

Sugar produced wealth for some but also cultivated insecurity. Declining sugar prices and sugar permit exceptionalism formed the foundations for ethnic violence that still lingers. Rigid state allocation of land for sugar production enabled conditions for famine. “Sugar lords” invested their profits into opium production. Crime such as theft and holdups increased around the trade of sugar. Thugs became more prominent in villages with elites using them to expand and protect land used for sugar cultivation as well as to discipline labour. Villagers that protested about falling sugar prices as well as forced land conversion could find their crops torched, or alternatively they burnt down plantations’ sugarcane crops in acts of resistance. In response, colonial police became deeply entangled with sugar. Dutch police (Marechaussee) battalions were posted to Java to curb sugarcane theft as well as arson attacks on sugar plantations. After the Japanese occupation began, military police (Kempetai) took over sugar plantations and coercively extracted from wealthy sugar-rich families.

Newly independent Indonesia was similarly dependent on sugar. After the Second World War and the National Revolution, Indonesia had less than half of its sugar processing capacity. Early governments needed to generate revenue to engage in trade for necessary machinery and textiles, which they did by reviving the decimated sugar industry. Private smallholder sugarcane farming occurred but its scale remained minor. Revival really meant securing and funding plantations. Revival also meant the sugar industry’s colonial-era sins, such as heinous working conditions and extortion, were largely unaddressed. Many state officials became entangled with private capital to take over Dutch sugar enterprises. Independence leaders and officials’ quick decisions made to support the national economy meant the structure of colonial sugar cultivation and processing was retained during decolonisation (Indonesianisasi).

While there was structural continuity, political tensions among workers at sugar plantations found new avenues for expression. During the “be prepared” (bersiap) period of the revolution (August 1945 to December 1946), long pent-up resentment felt at some sugar factories erupted in violence and murder. Sugar plantation workers became deeply involved in the new nation’s political change and many later returned to work at plantations as hardened revolutionaries. Sugar plantation unions, which colonisers had crushed, emerged again with connections to ideologically driven political parties and Islamic organisations. During this period, the independent state was often without the means to sustain control for extracting revenue in sugar enclaves. In the years immediately after the National Revolution, the amount of sugarcane plantation destroyed or stolen reached between 15 and 20 percent annually. Like its colonial predecessors, the newly independent government’s attempts to maintain control included assigning soldiers and police to protect sugar plantations.

Military involvement in sugar became even more entrenched after plantation nationalisation and Sukarno’s authoritarian turn in 1957. As newly formed state sugar plantation companies gained control over formerly Dutch enterprises, soldiers became more heavily involved to supervise financial administration, and deal with land and labour disputes. Military leaders needed to find money for their underfunded units or departments and sugar plantations were a useful source of revenue. The practice of soldiers extracting from the sugar trade occurred beyond plantations, too. A prominent example of military engagement in the sugar trade in this period involved a future president, Suharto.

From the late 1940s, Suharto—then a Lieutenant Colonel – lent army trucks to businessmen for sugar transport. He also purchased, or even sometimes seized, sugar from mills to sell onto middlemen. Later in 1957, while commanding a deep-water port in the city of Semarang, Suharto collaborated with future oligarchs such as Sudono Salim (Liem Sioe Liong) and Bob Hasan (The Kiang Seng) to smuggle and export sugar to Singapore. According to biographer David Jenkins “extortion and straight-out theft” describes Suharto’s operation at the port in those years. Suharto’s racketeering even meant he was nearly dismissed from his position by army chief of staff General Nasution.

Once Suharto became president, his militarised government further entangled itself with sugar production and processing to generate revenue. The government created state-owned sugar plantation companies out of the nationalised Dutch estates. These companies milled most domestically sourced sugar even as private smallholders became more important to overall sugar production. But really, sugar producing smallholders participated in state directed sugar distribution chains despite a veneer of change. The New Order government initially maintained a long-term system of forcing sugarcane farmers to rent land to mills. A regulation that was introduced to increase production efficiency by ending forced land rental, also had the effect of enabling village elites to dispossess smallholders of land. Those elites then sold sugar into the same state-owned mills. Moreover, soldiers and the police, in conjunction with irrigation officials, determined allocation of smallholder lands for sugarcane production.

Further up the sugar chain, the National Logistics Agency (Badan Urusan Logistik, Bulog), partly led by former soldiers, absorbed output from mills and became the sole trader of sugar. Bulog licenced sugar import and distribution contracts to Suharto’s cronies, including conglomerates controlled by his children as well as Sudono Salim. These contracts were very lucrative as Indonesia became, in the 1980s, one of the largest sugar importers in the World. This dominance meant Bulog had an enormous influence on prices.

Post Suharto sugar marketcraft

After Suharto’s downfall, the longstanding dynamic of prosperity and crime continued to coalesce around sugar. The removal of Bulog’s monopolies in 1999 meant imported sugar readily flowed into Indonesia and caused a sharp price decline. This new competitiveness caused a shock to sugarcane farmers as well as mills, represented by their associations. The emergence of agricultural commodity farming and trading associations are feature of post Suharto democratisation. There are many such associations for sugar.

The interests of diverse sugar associations, such as the Association of Indonesian Sugarcane Farmers (APTRI), the Association of Sugar and Flour Entrepreneurs (APEGTI), and the Indonesian Sugar Association (AGI), the latter with its membership comprised mostly of state-owned plantations, aligned in response to the price decline. They aggressively lobbied the government for re-introduction of sugar import restrictions and were successful in 2002. Soon after, just several state-owned plantations were legally able to bring sugar into the country. The government reintroduced these sugar import restrictions just as it was introducing decentralisation reforms that meant local governments gained more power to act in the sugar trade. The subsequent confusing regulatory landscape and the sidelining of private sugar merchants that prospered briefly after Suharto’s downfall led to a re-emergence of sugar smuggling.

Near the estuary of the Asahan River in North Sumatra is a small port almost opposite Malaysia’s Port Klang, a special trade zone around 180 kilometres away. Many such “veins” for smuggling contraband exist along the coast, but from this small port many thousands of tons of sugar flowed into Indonesia illegally after the re-introduction of import restrictions. The small port lays next to a highway. After unloading, workers quickly transferred contraband sugar onto waiting trucks and whisked it towards metropoles to become mixed into value chains trading legitimate sugar.

For many smugglers, the possibility of finding fortune in smuggled sugar was worth the minimal risk of jailtime. Making illegally imported sugar legitimate was not particularly problematic. One regular method included smugglers paying officials to create permits to legalise sugar after it was already in Indonesia. A reporter aptly said the restrictive sugar regulations “crumbled like donut dough in the hands of an official wanting an envelope (angpau)”. Moreover, the threat from the state for enforcement was not asymmetrical. A high-ranking customs official near the port claimed there were only 20 officers to deal with a nearby city full of smugglers. One junior leader at the port believed thugs (preman) would react strongly if their livelihoods dependent on sugar trade became disturbed.

But there were some arrests. One notable sugar-related arrest in the early post-Suharto period was a Golkar politician from South Sulawesi, Nurdin Halid. He held prominent leadership positions. Aside from being one of the Golkar party’s main leaders, he was head of the All-Indonesian Football Association (PSSI) (2003-2011), as well as Indonesia’s Cooperative Council (Dewan Koperasi Indonesia, Dekopin)(1999-2004, 2009-2019)—a representative body for savings and small loan banks. While a member of the parliamentary commission on trade Halid, along with his brother and several cronies, took part in a swindle involving more than 73,000 tonnes of illegally imported sugar. The police, rather than the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) that was then operating at a more limited capacity, were involved in prosecuting Halid’s sugar smuggling case. Eventually the illegal sugar import charges against Halid were dropped, but he was nevertheless jailed for other commodity trading cons.

Further details about Halid’s links with sugar and the police reveals a more complicated picture. Just after Halid went to prison in September 2007, thieves stole 3,000 tonnes of his sugar from South Sulawesi Customs. In addition to the customs warehouse manager and supervisor, the police investigated one of their own, a midranking officer described as a witness to the theft. After prison Halid was elected head of Dekopin for two more five-year terms over the decade 2009 to 2019 and was only recently ousted trying for another. A prominent member of Dekopin is the police employee cooperative (Induk Koperasi Kepolisian, Inkoppol), which is itself involved in the sugar trade.

Police and military employee cooperatives invest in raw sugar importation. These investments are partly justified in terms of helping control consumer prices as well as supporting their budgets. Their participation in sugar importation is above board and, despite criticism from national auditing authorities and members of civil society, occurred with ministerial approval. A 2005 review for police finance reform even saw increasing revenue at police cooperatives as a solution to help curb other sources of informal financing while addressing the institution’s budget shortfalls. Police and military cooperatives help import raw sugar from overseas for processing with several members of the Indonesian Refined Sugar Association (AGRI) which formed in 2004 soon after restrictive import controls were introduced.

Polda Metro Jaya in the Sudirman Central Business District (SCBD). The SCBD is a development of the Artha Graha group. Cropped photo by Dino Adyansyah on Flickr. (CC BY 2.0)

Conglomerates owned by oligarchs, some of whom have long established links to security forces, fund these sugar-refining enterprises and have significant access to an exclusive domestic sugar market. Membership of sugar markets regulates companies means to trade. Politically connected sugar players themselves sometimes even own commodity trading markets. One such figure is Tomy Winata, a tycoon with links to security forces and political parties. His conglomerate Artha Graha owns the Jakarta Commodities Market (Pasar Komoditas Jakarta, PKJ) designated by the government for large-scale sugar trade auctions. In addition to owning a government-designated market for sugar trading, Artha Graha owns one of the companies that trades there, which is also a member of AGRI, and is a major sugar importer in conjunction with Inkoppol.

AGRI members’ appear likely to benefit further from regulation stemming from the controversial Omnibus Job Creation Law (Undang Undang Cipta Kerja No.11/2020). Sugar related regulation in the law and Ministry of Trade regulations could mean only state plantations and large industrial-scale sugar traders, nicknamed “samurai”, are able access sugar import licenses. Many of the eleven “samurai” businesses are members of AGRI. Powerful Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs, and former General, Luhut Panjaitan said, “Sugar will be imported only by the food industry that needs it. So it’s not from other people so it doesn’t become a game”. Some industrial users of refined sugar, along with Indonesian Entrepreneur’s Association, worry that this new regulation goes against previous attempts to enable more competition, and will lead to further entrenchment of AGRI members’ dominance in the sugar trade. But before accepting the two differing positions as opposite sides in a hypothetical debate, it is worth asking who is actually willing to compete with entrenched players in Indonesia’s sugar markets?

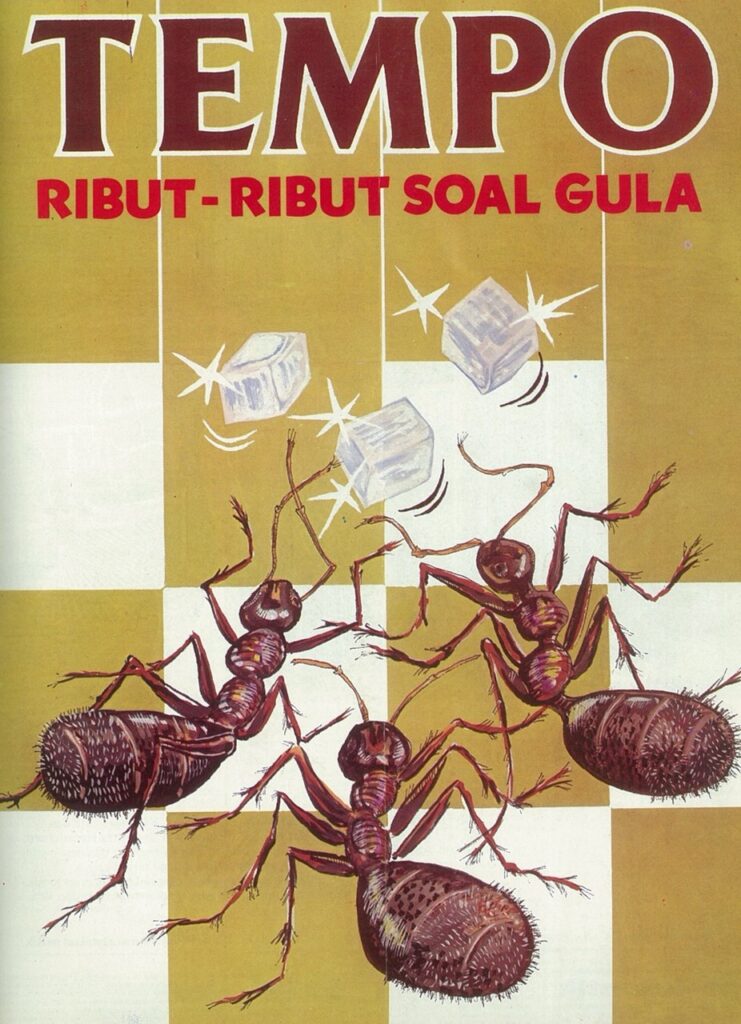

‘A fuss about sugar’, the cover of Tempo magazine, No 39, 22 Nov 1980

At the subnational level, newer sugar traders have links to coercive power, sometimes including security institutions beyond the police and military. For example, according to some research, former members of the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM) connected to former two-time Governor (2007-2012 and 2017-2018) Irwandi Yusuf, were awarded many of the province’s sugar quota licenses between 2007 and 2012. Importers more removed from the former Governor’s immediate patronage network then purchased these licenses with agreements that allowed the original holders cuts, without having to involve themselves in sugar distribution. These relations of sugar patronage are part of a broader “combatants to contractors” transition also found in Aceh’s construction sector.

Other new sugar players use existing political connections that competitors lack. For example, former Minister of Agriculture Amran Sulaiman allegedly sped up the approval process for the construction of what is now now the largest sugar plantation and processing factory in Indonesia. From 2016, the government requested tender submissions for an enormous new sugar plantation and factory located in Bombana, Southeast Sulawesi. The government promoted this new plantation and factory as necessary in terms of reducing dependency on foreign sugar. Of the 300 submissions to acquire the rights for sugar the plantation, Sulaiman’s cousin and former deputy treasurer for the Jokowi-Maruf Amin presidential campaign, Andi Syamsuddin Arsyad (also known as ‘Crazy Rich’ Haji Isam), a coal magnate, gained the license.

In October 2020, President Jokowi opened the sugar factory in Bombana declaring, with Sulaiman and Haji Isam present: “This is courage. Courage to open an investment and business in this place. This is what we must appreciate and value.” His remarks sounded as though he had arrived at a Wild West frontier with land of little value. Wealth from small-scale gold mining on the land converted for sugar plantation actually flowed into the area’s off-budget economy. But the conversion of thousands of hectares for sugar production and the factory dispossessed farmers who valued the land.

Indonesia’s agro nationalism in the pandemic

"Can Indonesia have food security without security?" Colum Graham looks at who really benefits from the government’s recent measures to address Indonesia’s food crisis.

Available coverage of the sugar plantation development at Bombana suggests there was an absence of protest from the dispossessed. But elsewhere recently, land conflict at sugar plantations has been intense. One recent case of land conflict in Tulang Bawang regency in the province of Lampung illustrates the power of plantations backed by security forces with stakes in sugar capital. For a long time, the land now used by the Bangun Nusa Indah Lampung (BNIL) company has been a site of conflict. In the early 1990s, security forces allegedly used gunfire to herd elephants from a national park through nearby transmigrant villages to make residents flee and assist BNIL to claim the land. Reports from human rights organisations say villagers had to sign miserly compensation agreements, which they only later discovered were for land, or face torture.

Tensions between BNIL and surrounding communities, many comprised of transmigrant villagers, were fraught for two decades before boiling over in 2015. Given sugar’s high price and its national prioritisation, some companies use it to replace other cash crops. BNIL even wanted to replace palm oil in its plantation with sugarcane. But then-Regent of Tulang Bawang Hanan Rozak, now a member of national parliament, refused BNIL’s request to convert palm oil land for sugar production because their application did not include an environmental impact assessment.

The Regent’s refusal became entangled with broader longstanding communal grievance about the legitimacy of BNIL’s land claim and threats to employment. Emboldened, thousands of aggrieved members of the “Farmers Union of BNIL Eviction Victims” attempted to occupy the plantation. Protests about BNIL even reached the presidential palace in Jakarta. In October 2016, conflict between members of the farmer union occupying the plantation and ‘Self-Sufficient Community Security Forces’ (Pam Swakarsa) protecting it erupted. Dozens of motorbikes and security posts were torched. With the clashes serving as additional justification, the actual police moved in, disbursed the occupiers, and arrested the accused ringleaders of the occupation including a charismatic priest Sugianto, who reportedly attempted to ensure occupation was nonviolent.

While we might look at this case in isolation as reported, we should see it as part of a broader pattern of sugar politics. Much about this disbursal of Farmers Union of BNIL Victims by the police reproduces the long-term relations between security forces and plantations that we have seen earlier in this brief chronology of the political economy of sugar in Indonesia.

Nowadays, BNIL cultivates sugarcane.

What is new?

Aside from the emergence of representative sugar business associations in the post Suharto democratic landscape, then Regent Hanan Rozak’s rejection of BNIL’s land conversion request in 2015 might indicate potential separation between the power of sugar capital and political decisions in one regency of Lampung province. But further analysis of the province’s elections indicate sugar capital actually saturates its politics.

Indonesia’s agro nationalism in the pandemic

"Can Indonesia have food security without security?" Colum Graham looks at who really benefits from the government’s recent measures to address Indonesia’s food crisis.

Just one hundred kilometres southeast of the BNIL sugar plantation by road is another owned by the Sugar Group. Ridho Ficardo, the son of one of Sugar Group’s directors, became the youngest ever Governor of Lampung in 2014 at 33 years of age. The company, famous for its popular Gulaku shelf-product found in Indomaret and most grocery stores, funded Ridho’s costly campaign to have someone in power to regulate on its behalf. In the most recent 2018 Lampung gubernatorial election, despite their man Ridho running as incumbent, the company backed the eventual winner, Arinal Djunaidi, too.

But that news of sugar scandals even appears at least allows for recognition of what is problematic. Corruption within Indonesia’s state-owned sugar plantations in the last decade, such as sugar distribution contracts and tender process bribery involving plantation bureaucrats, has frequently appeared in the news. Beyond the case of Nurdin Halid, other prominent politicians’ careers have recently ended because of underhanded dealings in the sugar trade. For instance, Irman Gusman, former speaker (2009-2016) of the Regional Representative Council (DPD), received a four-and-a-half-year sentence in prison (later reduced to three) in 2017 for accepting bribes for sugar purchasing licenses in West Sumatera.

More prominently, former Minister for Trade Enggartiasto Lukita (2016-2019) was linked to bribery for sugar auction permits in a recent corruption case. In the trial of former Golkar parliamentarian Bowo Sidik Pangarso—prominent for planned “dawn attack” vote buying in the 2019 elections and now himself in prison for fertilizer bribery—a witness accused the former Trade Minister of offering a bribe to Pangarso for securing PKJ as the designated government sugar auctioning market. When questioned about the accusation Lukita denied involvement, but just a few months later he lost his position in Jokowi’s second term cabinet without clear public explanation.

Rather than see such sugar scandals—be they land conflicts, instances of corruption, collusion, or high prices—in isolation, recognising the context that enabled them is useful for understanding possibilities for moving forward. The effects of decisions about sugar made during tumultuous periods in Indonesian history linger into the contemporary era. Progress may mean political leaders’ revise decisions made long ago in totally different economic contexts and disrupt entrenched sugar patronage networks. Unwinding relations of sugar patronage is all the more difficult without also reforming security force financing. Further, lowering high sugar prices may not be a useful goal in terms of public health. Diabetes and other sugar related illnesses are increasingly prevalent in Indonesia. Leaders and officials will want to make quick decisions about these difficult issues as they have done in the past. But sidestepping sugar’s actual political economy and its roots as too difficult may render any future reforms toothless.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss