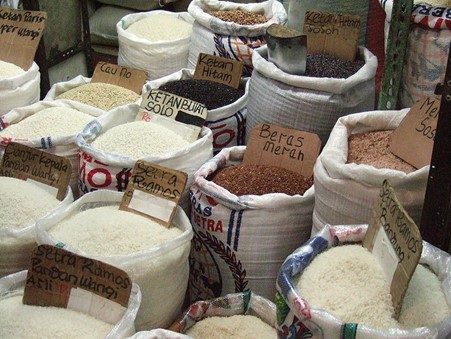

Last April President Jokowi appeared frustrated by the discrepancy between the falling value of unhulled rice (gabah) that farmers sell to brokers before processing, and the rising price of hulled rice (beras) that consumers purchase: “The price of gabah has fallen, so the price of beras should have gone down as well. Farmers do not benefit and the people lose. Who benefits? Find them”, he said.

By focusing on traders and their representatives, we can see the collusion with politicians that shapes Indonesia’s rice racket. Further apparent from focusing on the actors involved is that despite government and lobbyists’ claims about representing small players, their actions more support big businesses that already dominate the rice trade.

Indonesia’s rice prices are high. The average price of beras is over double the world average, while gabah costs nearly the same as the world average for already processed rice. Media reports suggest that high rice prices nowadays stem from seasonal supply shortages, import restrictions, and mafia racketeering.

Leaders often use the term “mafia” to blame shadowy figures without implicating anyone in particular. From afar, trying to see who is benefitting from illicit exchanges in the rice trade is near futile. Instead, to see who is benefitting, it is more productive to focus on traders.

Officials involved have suggested as much. When rice prices began to skyrocket in mid-2006, Sutarto Alimoeso, then Director General of Food Crops in the Ministry of Agriculture said, in response to shortages of subsidised rice, that traders were able to set the prices.

Jokowi is well aware of who these traders and politicians are. Yet his apparent frustration more reflects awareness of distributive discontent among “the people” than intent to intervene. Indeed, his government’s interventions in the rice trade never go beyond incremental measures because of the strength and scale of the vested interests involved.

Rice prices and regime transition

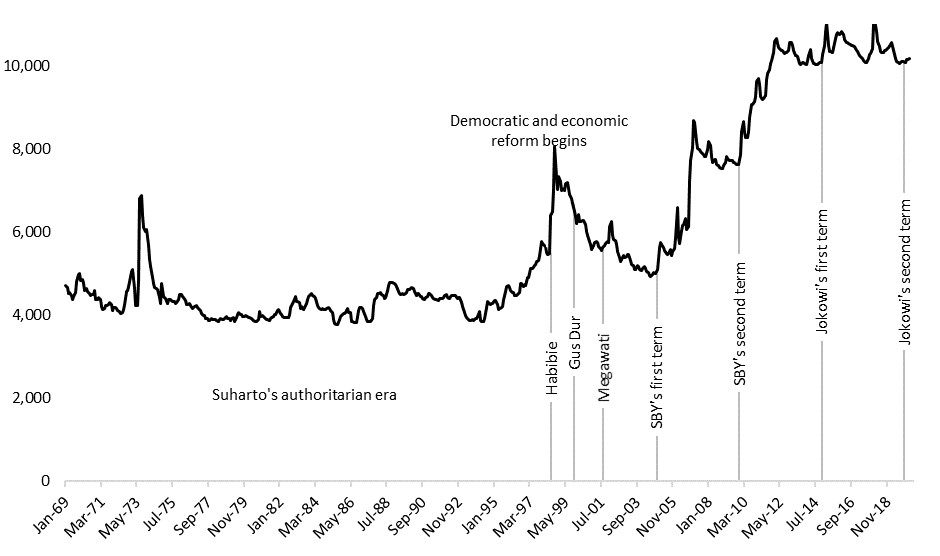

Indonesia’s rice prices increased coincided with liberalisation and democratisation in the post-Suharto period. Post-authoritarian freedoms allowed agricultural traders and associations to re-emerge and exert influence to extract maximum profits in commodity chains for their members.

For much of the authoritarian New Order period (1966-1998), traders and their associations were absorbed into regime-sanctioned functionally representative groups that fed Suharto’s franchise. In the months prior to the mass killings of late 1965 and early 1966, rice prices skyrocketed. In the aftermath, as well as destroying peasant representative organisations, the Suharto regime coercively reorganised agricultural traders and their representative associations.

The result of this state co-optation of the rice trade meant that for much of Suharto’s era, rice prices were stable and similar to world averages. Suharto saw low stable rice prices as necessary to prevent hunger and maintain political stability.

To achieve rice price stability, Suharto used the National Logistics Agency (Bulog). Bulog is responsible for state food procurement and distribution. As well as facilitating Indonesia’s food import contracts, Bulog absorbs domestic rice at the government’s purchase price for stock. During the Suharto era, Bulog was very powerful and one of Indonesia’s most corrupt institutions.

Average monthly rice prices, January 1969 – March 2020 (adjusted for inflation to 2012 values). Rice price data from Arianto Patunru (forthcoming), “Is Greater Openness to Trade Good? What Are the Effects on Poverty and Inequality?”

After Suharto and the exposure of corruption scandals, Bulog’s status changed from a powerful centralised government agency to just another decentralised state-owned enterprise. Although pruned, Bulog remained the most important actor in the rice trade because of its influence over prices.

The most dramatic rise in rice prices after the Suharto regime occurred during both of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s presidential terms (Figure 1). Under Yudhoyono, attempts to alleviate farmers’ poverty by increasing Bulog’s purchase price of gabah helped trigger overall prices to rise.

Somewhat ironically in a newly deregulated institutional context, each time the president set new recommended rice prices traders justified ever-higher gabah purchase and beras sale prices to maintain and even increase profit margins and prevent Bulog from absorbing their rice.

Although government intervention to raise set prices is intended to alleviate poverty, traders benefit most from increasing their profit margins while smallholding rice farmers try to recoup ever-higher livelihood expenses from still relatively low-value harvests. High beras prices can even prevent harvests making it to market. I have often encountered smallholders who saved a rice crop for their household’s consumption because the price of beras per kilogram was too high.

Politically powerful actors have an interest in rice prices remaining high. Traders who profiteered during Yudhoyono’s time in power are still very influential in the rice market. Moreover, today, unlike during Suharto’s era, many rice traders and their lobbyists are more independent, given their market power and political connections that are not subservient to the Jokowi administration.

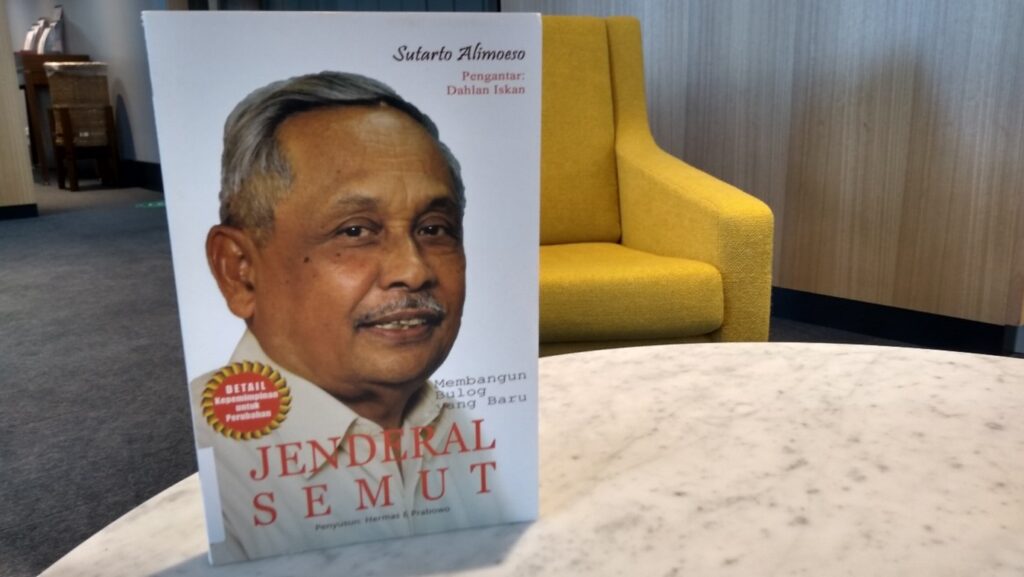

Sutarto Alimoeso is a useful example for appreciating the relationship between elite political power and the rice trade. He is a close childhood friend of former President Yudhoyono, a schoolmate from the early 1960s in Pacitan. This friendship later bore employment benefits. During Yudhoyono’s second presidential term in 2009, Sutarto was Director General of Bulog, a period in which the president issued repeat special instructions to increase the government’s purchase price.

Promotional biography of Sutarto Alimoeso ‘Ant General’

Sutarto’s promotional biography is called Jenderal Semut, or ‘Ant General’ because he claims to have enabled smaller traders, or ants, to sell to Bulog and gain from government set prices – previously a privilege for larger traders with large-scale purchasing agreements.

After Bulog, Sutarto became chairman of the nation’s most prominent rice traders’ lobby group, the Rice Traders and Millers’ Association of Indonesia (Persatuan Penggilingan Padi dan Pengusaha Beras Indonesia: PERPADI). A successor to colonial-era rice milling and trading associations, PERPADI had a small number of members through the Suharto era. Yet after the dictator’s downfall, its membership grew exponentially.

In 2015, Sutarto claims PERPADI had over 180,000 members throughout the archipelago. The vast majority comprised small millers and traders, though it reportedly represents around 2,000 larger rice businesses too. PERPADI’s leaders are powerful voices within the rice trade. As Sutarto’s ghost-writer put it in ‘Ant General’, the chairmanship of PERPADI is strategically important: “The closer the access is to the chairman, the more access to power, and in turn more business opportunities. This is an open secret”.

The Cipinang rice market and politicians

PERPADI’s main leaders operate at Indonesia’s largest rice market in Cipinang, East Jakarta, which is directly opposite a prison that houses some of Indonesia’s most notorious inmates. A number of rice traders at Cipinang have somewhat less notorious cases in Indonesia’s Supreme Court database.

Much of the Cipinang rice market, like much of East Jakarta and Bekasi, has frequently been oppositional for Jokowi’s administration and the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP). While he was Governor of Jakarta (2012-2014) Jokowi’s relationship with the market and PERPADI soured due to unfulfilled infrastructure promises and an effort to relocate traders. The market’s rice trader cooperative went on to support the Prabowo Subianto-Hatta Rajasa presidential ticket in 2014.

In subsequent years, tensions continued between PERPADI members at Cipinang and government representatives, with particular disputes becoming public. For example, in 2015, PDIP supported action against alleged fake rice sales (involving plastic pellets resembling rice) at Cipinang, a practice denied by PERPADI Jakarta division chairman Nellys Soekidi. Such cases occur in a broader context of government attempts to stabilise prices and Cipinang traders’ tactics to negotiate such regulation.

Price stabilization solutions include “market operations” (operasi pasar), where traders, many of whom are represented by PERPADI become obligated to sell Bulog-supplied rice at its mandated ceiling price. The government appears prepared to be coercive during these “market operations”. PDIP Governor Djarot (2017) threatened to evict from the market those recalcitrant traders who disregarded ceiling prices.

A more peculiar market operation to stabilise prices in 2015 involved then-Minister of Trade, Rachmat Gobel, who claimed that mafia practices caused the soaring price of rice. At the time Gobel himself was part owner of a rice mill in East Java, PT Lumbung Padi Indonesia, which business records show has connections with a shopfront at Cipinang rice market. Was he taking action against himself?

Such price stabilisation operations appear even more tokenistic as government critics attain positions in the market’s institutions. Recently Sudirman Said, a Prabowo-affiliated politician, former natural resources and energy minister (2014-2016) who Jokowi dismissed, became the President Commissioner of state-owned enterprise PT Food Station that leases shops at the Cipinang market to traders.

Tension about collusion between traders at Cipinang and politicians emerges during elections. During the runoff election for the Governorship of Jakarta in 2017, the treasurer of incumbent Basuki Tjahaja Purnama’s re-election team, Charles Honoris, a national-level parliamentarian for PDIP and scion of the MODERN conglomerate, tried to shame PERPADI’s vice chairman Billy Haryanto.

Ini Billy. Mafia beras pendukung paslon 3. Tukang fitnah. Nih mukanya. @ulinyusron @Takviri @ratu_adil pic.twitter.com/eIo4Ba9CxW

— Charles Honoris (@charleshonoris) April 18, 2017

Haryanto allegedly supported the election winner, a Gerindra Party cadre and former education minister who Jokowi also dismissed, Anies Baswedan. Yet Cipinang traders sell rice to any politician needing votes. Despite supporting Baswedan, Haryanto still sold over 60 tonnes of rice to the Ahok campaign through PDIP politician Aria Bima, among others.

With little self-consciousness about his status as a rice trader, Haryanto makes direct appeals to the president. During the 2019 presidential election season, although supporting for Jokowi, Haryanto nevertheless requested the incumbent president not inspect the market, saying such a visit would disturb traders. Later that year, Haryanto held an event attended by hundreds of players at his badminton club, to announce support for Jokowi’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, in his campaign for the mayorship of Surakarta (Solo). Indeed PERPADI’s opposition to the Jokowi administration and PDIP is selective rather than rigid. After all, PERPADI sometimes needs people in high office to cooperate.

Perpadi “representing” small business

PERPADI purports to support small rice millers and traders in the face of emerging larger competitors. In July 2017, the chairman of a number of parliamentary committees on agriculture-related issues, Herman Khaeron from Yudhoyono’s Democrat Party, said competition with larger factories in the absence of government protection meant for the closure of smaller rice businesses. Indeed, reports at the time suggested 40 percent of PERPADI members in East Java closed their operations due to competition with the “rice mafia”.

One of PERPADI’s more prominent efforts to support small traders in the face of larger competition was leading the dismantling of Indonesia Superior Rice (PT Indo Beras Unggul, PT IBU), a subsidiary of major instant food conglomerate Tiga Pilar Sejahtera (TPS).

TPS entered the rice market in 2010 and took advantage of rising prices. It purchased a number of mills, one being PT IBU located in Bekasi. TPS’s subsequent rice-based profits were a major factor in the company’s near-tenfold revenue increase from 2010 to 2016 (from 705 billion rupiah or USD 43 million, to 6.5 trillion rupiah or USD 434 million).

Their success did not last. In July 2017, police raided PT IBU warehouses and arrested its director, precipitating financial disaster for parent company TPS, with its directors also later sentenced albeit for different issues.

The raid immediately appeared connected to party politics. The President Commissioner of TPS, Anton Apriyantono, was Minister of Agriculture under Yudhoyono from 2004-2009 when rice prices first began to climb, a member of the opposition Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (PKS), and affiliated with oligarch and former chair of the Golkar party Aburizal Bakrie.

Then-Minister of Agriculture Amran Sulaiman of PDIP said the raids were not political and he was surprised to learn that TPS had connections with his predecessor Apriyantono. Yet even his own government questioned the motives for acting against PT IBU. A few months later Indonesia’s Ombudsman office claimed Sulaiman provided inaccurate data in relation to allegations of enormous losses incurred by the state because of PT IBU’s business practices which justified the raids.

As further details subsequently emerged, they raised more questions than answers. While PT IBU’s director was sentenced for fraudulently labelling lower quality rice as premium rice, a potentially more important justification for taking action emerged from PERPADI: PT IBU had cut out established brokers by buying gabah from farmers directly at prices slightly above average.

National Awakening Party (PKB) parliamentarian Erma Mukaromah, questioned why above average purchasing prices from farmers was problematic: “They [PT IBU] buy farmers’ rice at a higher price, how come they are accused of committing criminal acts?” Erma has a point: the government has even encouraged farmers to process their rice at small state supported mills so they hold onto more profit and cut out brokers.

Looking more closely at PERPADI’s role in the raids partly addresses Erma’s question. Billy Haryanto claimed he was a victim of TPS. He said they “… buy grain and rice at a more expensive price. Whether we want to or not we have to follow their price…” As a result, he said, TPS had long been the enemy of small traders.

Indeed, PERPADI appears to have played a role in instigating the raid against PT IBU. According to Tempo magazine, PERPADI was the alleged source of information for both the police and Ministry of Agriculture. Comments by leaders of both the Ministry of Agriculture and police suggest the raids were about supporting smaller traders.

The Director of Special Economic Crimes in the police force at the time reasoned, “Many rice mills have closed down. Small traders cannot compete because of their actions.” Amran Sulaiman claimed while farmers may benefit from PT IBU’s higher prices, everyone else is “killed”, meaning put out of business. Haryanto was very appreciative of Sulaiman’s work protecting small rice millers and traders: “Thank you very much and salute to the Minister of Agriculture Amran Sulaiman, who very bravely raided the warehouse of PT IBU… This crazy minister. Crazy and great!”, he said.

So, what of PT IBU and TPS’s fate? PT IBU’s factory in Bekasi is one of the largest in Indonesia, so could it really fall into disuse? After TPS’s bankruptcy in 2019, the much larger MNC Corporation, owned by tycoon-politician Hary Tanoesoedibjo, sought to provide a bailout. Worth noting, too, is that soon after the raids high-ranking military officials appeared as commissioners at PT IBU and TPS.

Big business and the public interest

With PT IBU’s factory still standing and larger players looking to take it over, does PERPADI really represent the interests of smaller rice millers and traders? It is a worthwhile question to ask since some of the main beneficiaries of PERPADI’s lobbying are far from minor players.

Though some companies at Cipinang market appear to be long-term medium-sized family operations, others have owners involved with some of Indonesia’s largest agribusiness corporations, such as Triputra, Sinar Mas and Wilmar. Notably, over the last several years, Wilmar has been expanding its rice operations by buying up large milling businesses in East Java, which sell into Cipinang.

Beyond the veneer of such corporations, there are important links between the rice trade and Indonesia’s more intriguing oligarchs. For example, the Jakarta office of former trade minister Rachmat Gobel’s part-owned rice mill is located at the Pacific Place building in the upmarket Sudirman Central Business District owned by Tomy Winata’s Artha Graha Group. Winata has a long history of interesting deal-making with state institutions, including the military, and Gobel has previously praised the tycoon.

As the world food price crisis of 2007-2008 was developing, Winata was expanding his ‘hobby’ in rice. For a mere pastime, Winata once chartered a plane with a day’s notice to follow then Vice President Jusuf Kalla to Chengdu to seal a rice seed deal. He has occasionally appeared with politicians to promote his rice seed enterprise. More recently, the charitable foundation Buddha Tzu Chi, with which he and fellow Artha Graha boss Sugianto Kusuma have strong links, collaborated with Billy Haryanto of PERPADI, the military, and police, to distribute rice for Covid-19 pandemic relief.

While the likes of Wilmar and Winata are big players, they are not the largest in the rice trade. The biggest player of all is state-owned enterprise Bulog, which tycoon-politicians influence too. Leading PERPADI’s representatives described here, themselves hardly small players, also have strong relationships with Bulog.

In Sutarto’s promotional biography there is a special insert explaining how Nellys Soekidi’s small rice trading business profited and grew as a result of his reforms at Bulog. In 2013, when the recurring issue of rice imports from Vietnam flared up, one trader said of Billy “He is a broker (calo), a middleman for Bulog. If you want to buy rice from Bulog you have to go through him”.

Further demonstrating close links between Bulog and PERPADI, the lobby group’s main office is in Bulog’s second office building in South Jakarta. Indeed, there is little separation between government and rice entrepreneurs’ interests. The thick entanglement of private and public interests is structural, has its origins in Indonesia’s colonial past, and has been perpetuated by major politician-businessmen in the post Suharto period.

One prominent example is the relationship between Bulog and former two-time Vice President Jusuf Kalla. He has influence at Bulog via medium sized Bank Bukopin, which he once controlled before selling to the conglomerate Bosowa, owned by his brother-in-law tycoon-politician Aksa Mahmud (its control is subject to takeover bid by South Korean bank Kookmin, which incidentally has also been busy taking over Cambodian rural microfinance giant Prasac). Bukopin has long been the bank for Bulog’s off budget finance.

In the immediate reform period of 1998-1999, Bulog’s systemic corruption became public as repeat scandals known as Buloggate I and II—the first of which memorably involved, among others, President Gus Dur’s personal masseuse Soewondo handling enormous amounts of money from Bukopin accounts—exposed how political actors appropriated substantial sums from the agency’s funds.

According to recent audits, significant amounts of Bulog’s listed cash reserves are still stored with Bukopin. A branch of Bank Bukopin, with its distinct canary-yellow logo, is on the ground floor of Bulog’s second office building, which to some may seem an oddity as most government buildings have state-owned rather than private banks on site. As well as sharing an office building with PERPADI, Bukopin’s microfinance subsidiary, Swamitra, appears the only lender with an office at the PT Food Station building in the Cipinang rice market.

Kalla, while seemingly far removed the day-to-day fray of the rice trade, has exerted influence over Bulog in recent years. For instance, it was Kalla that “examined” former Police General and head of the National Narcotics Board Budi Waseso to lead the institution. Kalla rather than the Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Trade, or Budi Waseso, announced both the possibility of rice imports and their cessation in 2018. Incidentally, when reflecting on the PT IBU raids, Kalla said “We want no one to take too much profit in this business”. He also denies there is a rice mafia.

Pak @jokowi pernah tanya RR, bagaimana caranya jadi orang terkaya di Indonesia dengan cepat ? Saya tidak mau jawab kecuali jelas kasusnya. Stlh Jkw jelaskan kasus Pejabat & kel-nya, baru saya jawab: “Gamoang Mas, ‘bisnis kekuasaan’ atau ‘Peng-Peng. Cepat”

Thus ia dipreteli! pic.twitter.com/NL0Kvcr5Vg

— Dr. Rizal Ramli (@RamliRizal) November 9, 2020

Yet of late, Rizal Ramli, who held ministerial portfolios under both Presidents Gus Dur and Jokowi and succeeded Jusuf Kalla as chair of Bulog two decades ago, has claimed that Jusuf Kalla’s wealth has increased considerably on annual rich list rankings since his time in high office because of his trading power. This trading power appears to have previously involved rice imports. Though we must remain circumspect about claims to do with Gus Dur’s decision-making, a new well-received biography suggests he dismissed Kalla as head of Bulog partly because of rice imports, among other irregularities.

A high-class protection racket and distributive discontent

Jokowi’s first administration moved to disrupt a powerful but more concentrated oil and gas cartel that prospered under Yudhoyono. In striking contrast, Jokowi has not seriously tried to intervene in the rice market to lower prices. Unlike the more concentrated oil and gas mafia, there a vast number of beneficiaries of high rice prices.

Intervention to lower prices could interfere with interests millions of farmers that rely on higher gabah prices, along with traders and millers that ratchet up consumer prices. Intervention would necessarily interfere with collusion between traders, the police, military, tycoons, and politicians. Really moving to lower prices would mean confronting a well-connected PERPADI that operates like a high-class protection racket.

Indonesia’s agro nationalism in the pandemic

"Can Indonesia have food security without security?" Colum Graham looks at who really benefits from the government’s recent measures to address Indonesia’s food crisis.

No need for door-to-door preman, this relatively opaque group appears to have enlisted the police, and even a minister, in its pursuit of gutting an old-money instant food corporation worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Selectively oppositional agricultural lobbying associations with connections to political-power like PERPADI are a feature of contemporary Indonesian democracy.

Yet is the public’s best interest really the first priority for politician-tycoons and the beneficiaries of PERPADI’s efforts? From time to time, food prices emerge as an issue of distributive discontent in popular politics. In 2019, mothers’ groups (emak-emak) campaigned prominently for the Prabowo Subianto-Sandiaga Uno presidential ticket partly because of exorbitant rice prices. Solutions such as ambiguously named “market operations” may prove superficial public relations spectacles to placate “the people’s” rice price discontent.

Nowadays, there are parallels between Indonesia’s rice price situation and the early 1960s, when “Domestic prices [were] almost wholly isolated from world market prices”. In this period of Indonesian history, we can see more severe political problems caused by high rice prices.

The inflation of already high rice prices was a contributing factor in the violence unleashed as the Sukarno administration collapsed. What if today’s high rice prices go even higher in Indonesia’s polarised political landscape?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss