If infrastructure policies are the brand of Joko Widodo (Jokowi)’s presidency, then roads are the hallmark of his re-election campaign. He claims to have delivered hundreds of kilometres of roads, including a 600km contribution to the long-overdue Trans Jawa network. This finally connects Indonesia’s most inhabited island from end to end and more than 1000km of border roads in the peripheries of the archipelago. Toll road projects that languished under previous administrations, like the Becakayu in Jakarta and the Bocimi in West Java, have also been rebooted and completed by Jokowi. These successes affirm his reputation as the president who works to deliver results, and are consistent with his campaign slogan during his first term presidential campaign: “kerja, kerja, kerja” (work, work, work).

I must admit I am one of the direct beneficiaries of Jokowi’s infrastructure drive. Travelling by car from my hometown Yogyakarta to Jakarta used to take around 12 hours—now it takes only 9 hours, or less. Such time efficiency is expected given the significant budget increase Jokowi has given to infrastructure development. From 2010–2014, infrastructure spending averaged just under Rp150 trillion (A$15 billion) annually. In 2015, he allocated Rp256 trillion (A$25.6 billion) and gradually increased it to Rp415 trillion (A$41.5 billion) in 2019.

Roads in particular take up much of the infrastructure budget allocation: the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, for instance, has allocated more than one third of its annual budget to road provision and management. Jokowi has also leveraged state-owned enterprises to take on a majority of the infrastructure projects, which supplies additional budgets for road investment. These efforts are all good for Indonesian development: having more roads increases the mobility of goods and people, creates market access, and fosters business activity; studies have confirmed the positive correlation between physical infrastructure and the growth of an economy.

However, for some of the country’s most developed provinces, having more roads may have negative consequences. In places like Jakarta, Bali, and Yogyakarta, roads are already congested and traffic congestion results in inefficiencies for the economy. Meanwhile, the desire to own a car is growing, especially among the middle class. Therefore, strong political will and effective policies at the national level are needed to address the problem: instead of just expanding roads, perhaps it is time for the government to also think about ways to limit the number of cars on them.

The Indonesian middle class and their cars

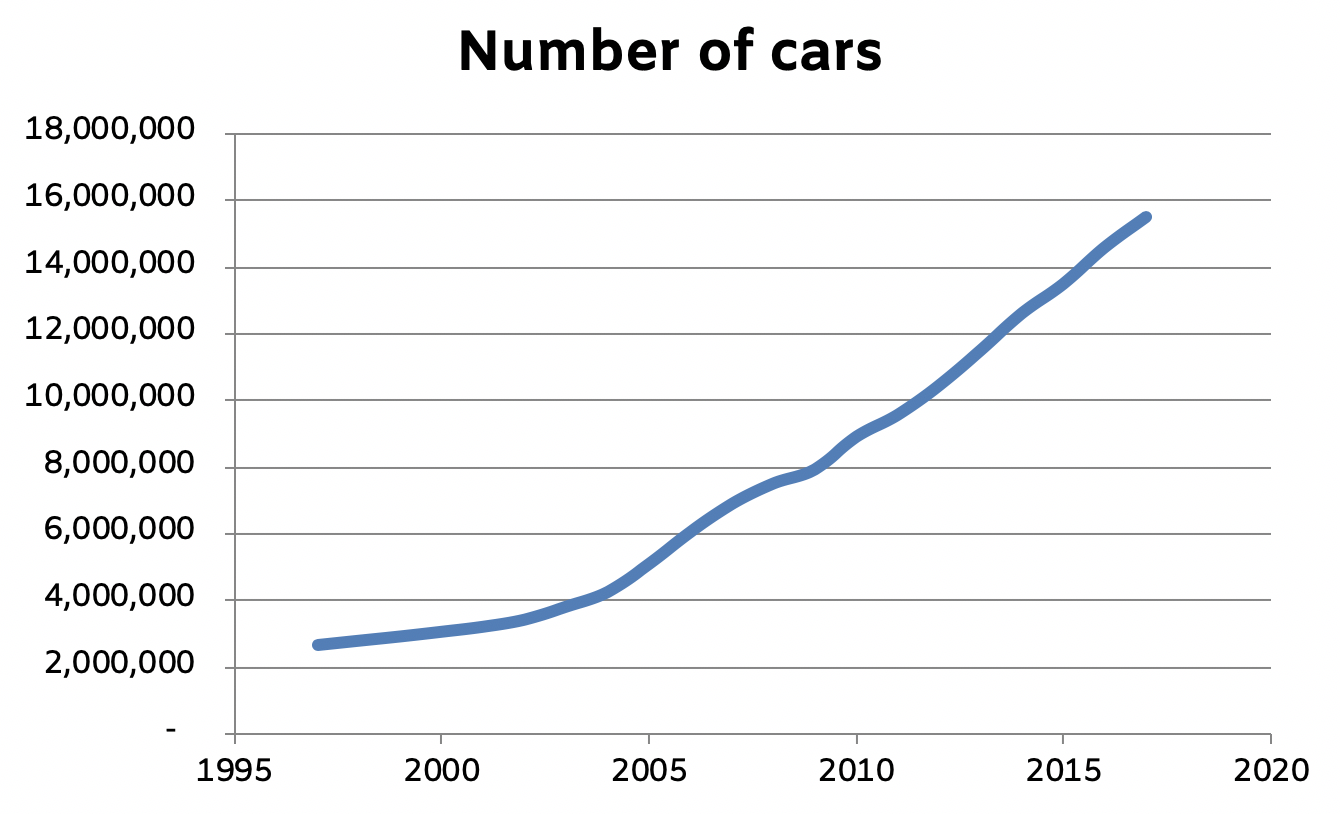

The number of cars in Indonesia has increased significantly over the last two decades. According to the National Statistics Agency (BPS), there were only 2.6 million cars in 1997. This number more than doubled to 6.8 million by 2007 and reached 15.4 million by 2017. These cars are mostly found in the Java provinces, with Greater Jakarta (3.8 million), West Java (1.5 million), and East Java (1.4 million) in the top three. Outside of Java, the highest number of cars is found in South Sumatra (915,000) and Bali (878,000).

Source: Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS)

The automotive industry is surely enjoying Jokowi’s administration. When he assumed office in late 2014, car sales were around 1.2 million per year. Yearly sales dipped in 2015 to 1.01 million units, but since then the trend has been relatively steady with small annual hikes: in 2016, 2017, and 2018, annual sales were 1.06 million, 1.07 million, and 1.15 million, respectively. Still, these numbers are all above the average annual sales over the last decade—a fact that is clearly appreciated by the car industry group. Recently, the Chairman of the Association of Indonesia Automotive Industry (GAIKINDO), Yohannes Nangoi, addressed Jokowi as “being most attentive to cars” given his construction of plenty of pro-car public facilities, such as highways and toll roads.

Two factors may explain the increasingly widespread presence of cars in Indonesia. First, Indonesians tend to see their social status as defined by car ownership. In 2014, a global survey by Nielsen found that among Indonesian car owners, 67% of respondents perceive car ownership as an important symbol of success, much higher than the global average of 52%. Meanwhile, 93% of Indonesian non-car owners perceive the lack of a car as a source of embarrassment, a much higher rate than the less than 50% averaged by other countries surveyed.

Second, people buy cars for pragmatic reasons, related to affordability and functionality. The Toyota Avanza, one of the best-selling multi-purpose vehicles on the market, ranges in price between Rp180–230 million (A$18,000–23,000)—a good deal for those within the middle income bracket. They can afford to purchase one on credit, with a light 15% down payment plus a long instalment period of up to 5 years, resulting in a monthly payment of less than Rp5 million (A$500).

Petrol prices are also relatively cheap. This month, while the global average price of petrol is US$1.13 per litre, the price in Indonesia is only US$0.70, cheaper than Vietnam (US$0.87), Thailand (US$1.12), and Singapore (US$1.57). Despite the free-floating fuel price policy introduced at the beginning of Jokowi’s presidency, to date, the pricing decision for petrol remains politically motivated. Last year, the government abruptly cancelled a price rise for subsidised “Premium” fuel just moments after Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Ignasius Jonan announced the plan.

Vehicle-related taxes and charges are also set at a level that does not hurt car owners. As a result, there are few monetary disincentives to deter people from purchasing cars. With an unreliable public transportation system in most provinces, in which schedules are unclear and routes are disconnected, using cars has become a sensible choice for the Indonesian middle class.

Cars and congestion

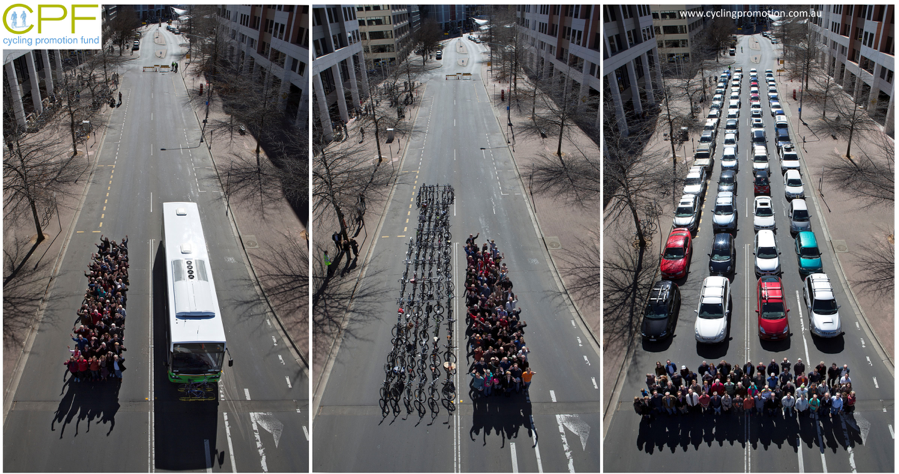

The problem with cars, when compared to other transportation modes, is just how much road space they occupy. This widely-shared photo demonstrates the difference in the amount of physical space that is taken up by 69 people when they choose from transportation options that include their own car, a public bus, or a bicycle. One individual’s decision to own a car may secure personal space, but at the expense of public space—this is essentially a negative externality. Social costs are even greater when health factors are taken into consideration, as seen in the deteriorating life expectancy of people living Jakarta as a result of the city’s air pollution.

Source: https://www.danielbowen.com/2012/09/19/road-space-photo/

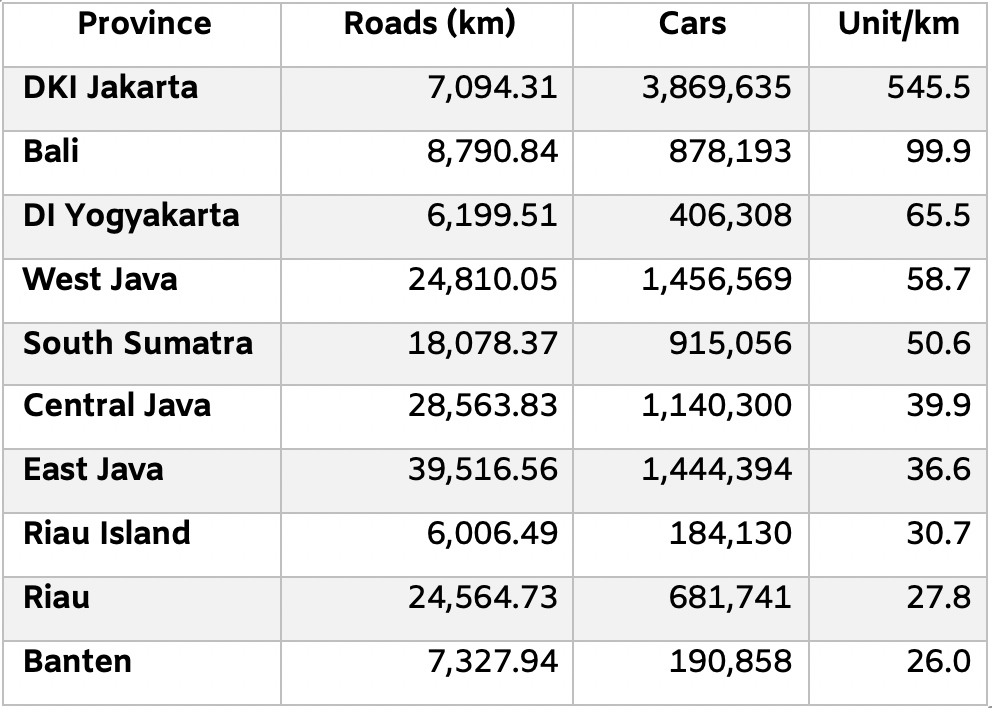

The 3.8 million cars congesting Jakarta’s roads have created some of the worst traffic in the world, which Jokowi himself acknowledges has gigantic costs for the economy. But taking a closer look at the data, we see that other Indonesian provinces seem to be following the same development trajectory. The table below provides a comparison (ratio) of the number of cars (units) to the length of roads (km) in 10 Indonesian provinces. The greater the ratio, the more cars occupy roads, on average. Jakarta is an outlier with a staggering rate of 545.5 units of cars per road kilometre. Bali (99.9) and Yogyakarta (65.5) come second and third.

Source: Analysis based on data from Ministry of Public Works and Housing (2017) and BPS (2017) CLICK TO ENLARGE

Traffic in the top provinces may not all be exactly like Jakarta. However, people would still find their major roads equally, if not more, congested during peak hours. In Yogyakarta, for instance, the wait time at intersections along the north section of city’s Ring Road are often as endless as at major junctions in Jakarta, such as Pancoran and Ragunan.

Jokowi’s policies: pro-infrastructure = pro-cars?

When it comes to congestion, the government’s usual response is to build more roads. In Jakarta, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing commissioned the construction of 6 toll road sections that will connect busy routes, including Sunter–Pulo Gebang-Tambelang, Kemayoran–Kampung Melayu, and Pasar Minggu–Casablanca. In Yogyakarta, the government has finally acted on a long-standing consideration of underpass construction and is in the process of building one now.

Jokowi must understand, however, that building roads will only address the supply side of road infrastructure. With his previous experience as a local leader (demonstrated by his 2 years as Governor of Jakarta and a 7-year stint as the Mayor of Surakarta), he should know that the demand side, which mostly comes from car ownership, also needs to be addressed. In other words, building roads is a partial solution. Unless the government limits the number of cars, their presence will grow uncontrollably.

Weighing Jokowi’s infrastructure projects in Eastern Indonesia

Out in the east, there is a feeling that Sulawesi has received disproportionate attention from Jokowi.

Traffic management, as well as the collection of vehicle-related taxes and charges, are the domain of local authorities, not the central government, but that does not mean the centre cannot get involved. National regulations can still be effective in bringing about changes at the local level. For instance, the central government could set a national guidance on competitive local taxes and charges for owning and using cars in congested areas, and earmark local revenues from vehicle taxes or parking charges for investment in public transportation systems.

The political economy challenges

This is not to say that cars are bad. But just like other goods, they’re good up to a certain point, beyond which there’s a diminishing return. Cars may benefit farmers living in rural areas or families residing in far-flung provinces, but in urban areas they’re problematic. With that in mind, government actions should be aimed not at eliminating cars from the market, but rather at ensuring that the number of cars is just right—so that no province is heading into a gridlock it never asked for. The issue of having too many cars is evident in Jakarta and will expand to other provinces in the next few years. As Indonesia’s economy is growing, the middle class is rising with its purchasing power, and developing an appetite for the social status embodied by car ownership.

Despite clear mechanisms and possible solutions, no politicians or policymakers seem willing to spotlight the issue, at least so far. Perhaps the political economy barriers are too significant. First among them is that the automotive industry creates jobs. The automotive industry, which contributes 10% of Indonesia’s GDP, has created 350,000 jobs (i.e. workers related to the production of cars) plus 1.2 million jobs indirectly, according to the Industry Minister Airlangga Hartanto. Second, vehicle-related taxes and charges have become a main revenue stream for some provincial governments. One of them is the vehicle ownership transfer fee (BBNKB), not exclusively from cars, that has accounted for over 30% of the local revenues in Riau Islands, East Java, Bali, Banten, and Southeast Sulawesi. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, making cars more expensive will only hurt the middle class, which may cost politicians their votes.

A lot of people say that class politics do not exist in Indonesia, but it can be seen in policy decisions that suit the interests of Indonesia’s middle class. Jokowi’s policy of cars and roads infrastructure is a policy that supports that middle class, who are simultaneously demanding more cars and less traffic. It’s unclear if they want to understand the necessary trade-off, unless a politician, policymaker or president dares to tell them that they can’t have both—which raises the question: is there such a person?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss