Over the last week, tens of thousands of students and activists have poured on to the streets of Indonesia’s major cities. Protestors are demanding legislators and the government halt the passage of controversial laws that place new limits on individual freedom and criminalise acts that insult state institutions, including the parliament and the president.

But what galvanised the students and brought them on to the streets was a decision to rush through a revised law on the KPK (Corruption Eradication Commission). The new law severely weakens the corruption watchdog by undermining the Commission’s independence and limiting its powers of investigation.

These protests are remarkable for a number of reasons.

First, these activists have revived the language of reformasi and liberal democratic rights in a way that no-one predicted. The quality of Indonesia’s democracy has been in decline for years. Under both President Yudhoyono (2004-2014) and Jokowi (2014-), institutions and norms that protect civil liberties – the rights of minorities and women, and the right to express one’s beliefs and opinions freely – have been eroded by those in power, and by conservative community groups too.

Analysts have long noted (and lamented) a lack of public opposition to this trend. Indonesia has instead been drifting toward a more illiberal order with very little popular resistance – until now.

Second, the protests appear remarkably bipartisan. Over recent years Indonesia has become more and more polarised. Popular opinion and public discourse on a range of issues has been divided along political lines – Jokowi supporters versus Prabowo supporters, and more pluralist Indonesians versus more Islamist Indonesians. But unlike the anti-Ahok protests in 2016/17, or the demonstrations against the election results in May, this time the street mobilisations have brought together Indonesians from across the ideological and political spectrum.

Love for the KPK and distrust of Indonesia’s parliament transcends Indonesia’s socio-political cleavages. Whether you’re a pluralist or Islamist, a progressive or conservative, a Jokowi or Prabowo voter, you’re likely to love the KPK and dislike the parliament and political parties.

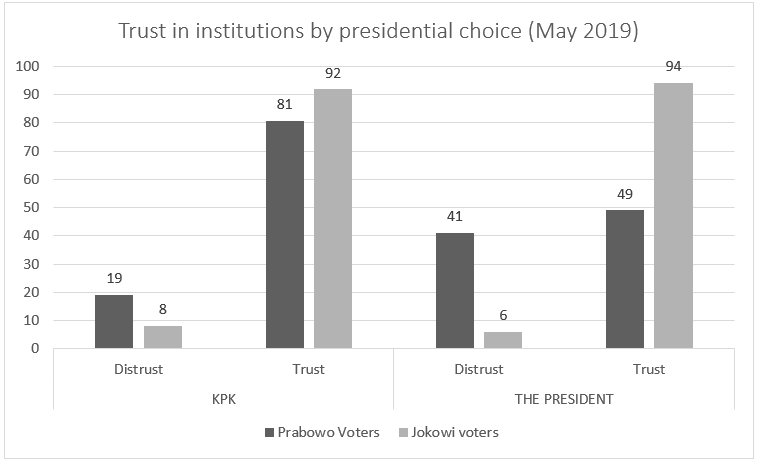

A brief look at recent data shows high levels of trust in the KPK across partisan divides. The table below presents the results of a post-election survey conducted in May 2019 by Indikator Politik, one of Indonesia’s leading polling institutes. Respondents were asked how much they trusted a whole range of institutions. The table compares responses to the KPK and to the office of the president, broken down by Jokowi versus Prabowo voters.

These data tell us that voters are still polarised –Jokowi voters overwhelmingly trust the office of the president, while Prabowo voters are far more divided. But they are not polarised when it comes to their trust in the KPK.

These data also show the overwhelming support that the KPK enjoys within Jokowi’s base, and help to explain the sense of betrayal and anger that many of the president’s supporters are now expressing on social media and on the streets. Presumably, the president and parliament decided to rush the KPK law through because they understood the depth of public support for the watchdog, and wanted to limit opportunities for critique and opposition. After all, almost every public poll for over a decade has shown the KPK to be one of the most trusted institutions among voters. Parliament and parties, meanwhile, have long enjoyed the least public trust.

There is much, however, that demonstrators do not agree upon. Only some, not all, are demanding the government pass a law on the eradication of sexual violence, for example. And despite the way these protests have often been cast in the foreign press, there are demonstrators who do not feel the government should remove the proposed ban on sex outside of marriage from the criminal code. It’s likely, in fact, that more Islamist-oriented students support the criminalisation of what they see as moral vice.

Still, the bipartisan flavour of the protests is significant given the backdrop of deepening political polarisation, especially in the wake of the 2019 elections.

A third reason these protests are remarkable is because of what they reveal about problems of representation in Indonesia. Elections have become firmly institutionalised over the last twenty years, and in poll after poll, Indonesians express immense support for elections at all levels of government. At the same time, many Indonesians do not trust or feel represented by either political parties or the politicians they vote for.

A recent study helps to illustrate the disconnect between politicians and voters when it comes to the particular problem of corruption. In late 2018, as part of a collaborative survey project with Edward Aspinall, Burhanuddin Muhtadi and Diego Fossati, we surveyed Indonesian politicians around the country. These were provincial politicians, not national ones. But they’re part of Indonesia’s governing elite and they’re members of the same political parties represented in the national parliament.

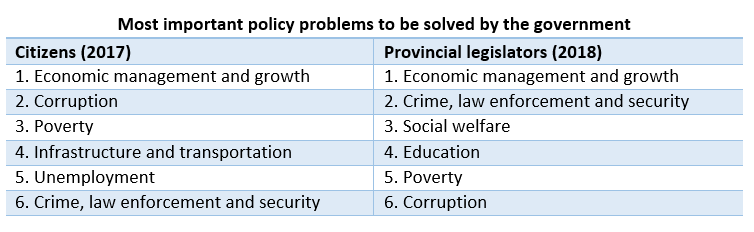

We asked them what they believed the top three policy priorities of the government should be and then we compared their responses to those of the wider population.

Both groups put the economy first. The second most popular priority for citizens, however, was corruption; for politicians, it was crime and law enforcement. On the other hand, crime and law enforcement was much further down voters’ list of priorities, just as corruption was not a major priority for politicians.

These data points help us understand public rage. Politicians have rushed through a self-serving bill to hamstring the KPK, and in the process wilfully ignored the priorities of their citizens. At the same time, they have prioritised revisions to Indonesia’s criminal code, when it seems very few voters count crime and security as a pressing policy concern. Those revisions include an equally self-serving passage that makes “insulting” – vaguely defined – the president and parliament a criminal offence. Both laws protect politicians from public criticism and oversight, and deepen the “deficit of accountability for elected officials” in Indonesia.

Politicians’ response to the backlash also suggests an inability to understand or empathise with the grievances of protestors. At the time of writing, the parliament had agreed to delay – but not cancel – revisions to the criminal code. Jokowi had still not revoked the KPK law. Members of his own party publicly criticised the idea, claiming that doing so would disrespect the authority of the parliament. The executive has mostly dismissed the students’ protests, telling them to voice their concerns through the legal system and challenge these laws in the Constitutional Court. The government increasingly tries to delegitimise the protests by blaming “anarchic” actors whose goal is not to defend Indonesian democracy, but rather to bring down Jokowi. And there is mounting evidence of police violence and repression.

It is now over a week since the demonstrations began, and students and other activists are no longer just protesting the content of these undemocratic laws. They are also protesting the government’s response. Most importantly, Indonesians from both sides of the political divide have come together to oppose what they see as a class of politicians and a political system that has failed to represent a deep and widely-held public desire for transparency and accountability.

It is now up to Jokowi to decide whether he will side with the system, or with the citizens who seek to change it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss