Indonesia’s political polling industry has boomed in recent years, with dozens of organisations of varying repute collating and publishing survey data ahead of the 2014 legislative elections. Yet despite this profusion of pollsters, among the most noticeable trends at recent elections has been a widespread tendency to underestimate the electoral support for Indonesia’s four largest Islamic (or Islam-oriented) parties.

The ‘big four’ Islamic parties in question are PAN (National Mandate Party) and PKB (National Awakening Party), Pancasila-based parties which retain links to Indonesia’s Islamic mass organisations; PKS (Prosperous Justice Party), a cadre party once touted as Indonesia’s most conservative electoral participant, which has adopted an increasingly centrist public image to broaden its popular appeal; and PPP (United Development Party), the sole Islamic party under New Order, which has maintained a conservative stance on key policy issues and continues to position itself as the party most capable of representing a broad Islamic constituency. The former two parties can be described as running on a ‘pluralist-Islamic’ platform, whereas the latter may be broadly described as ‘conservative-Islamic’ in character. PBB (Crescent Star Party), an Islamist outlier and the self-proclaimed successor to Masyumi, was the only non-parliamentary Islamic party which qualified to contest the 2014 election.

Former president Abdurrahman Wahid featured on a PPP billboard, Purbalingga, Central Java. Author photo.

In 2009, Islamic parties recorded their worst collective vote share of the post-authoritarian period. However, polling data published by many leading survey institutions ahead of the 2009 election predicted a sharper decline in their support levels than ultimately eventuated. A similar pattern was evident in 2004, when Islamic parties achieved far better results at the ballot box than survey figures had anticipated.

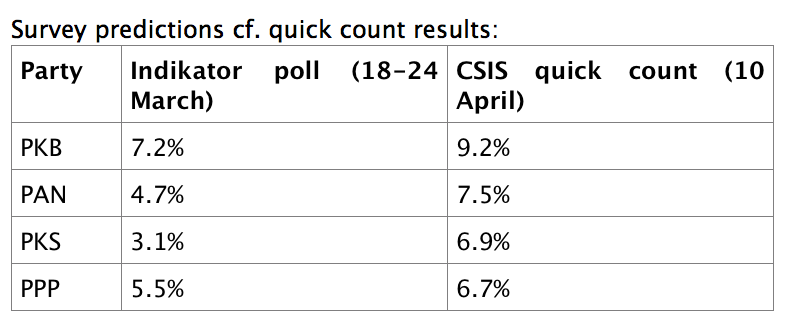

For many experienced Indonesia-watchers, the polling figures published prior to this year’s ballot would have induced a sense of deja vu. Almost every major polling organisation published surveys suggesting that Islamic parties were facing a sizeable reduction in their overall electoral support. For example, figures released by the highly respected Indikator polling organisation, based on surveys conducted from 18-24 March 2014, forecast middling to disastrous results for all four major Islamic parties. According to this data, PKS would fail to cross the parliamentary threshold of 3.5% – a disastrous result for the largest Islamic party in national parliament. While many observers assumed that PKS’s fervent membership would turn out in force to ensure it at least retained a presence in Senayan, the fallout from a major corruption scandal which over the past year engulfed former party president Luthfi Hasan Ishaaq persuaded most election-watchers that a severe electoral backlash was on the cards.

According to most pre-election survey data, the only Islamic party expected to significantly improve on its 2009 result was PKB, the Nahdlatul Ulama-aligned party led by the astute political operator Muhaimin Iskandar and bankrolled by Lion Air’s ethnically Chinese chief executive. While PPP was anticipated to remain steady, the appearance of party chairman Suryadharma Ali at a Gerindra rally alongside controversial presidential candidate Prabowo Subianto saw that party afflicted by open infighting during the latter part of the campaign period. Meanwhile, although PAN ran a well-funded and seemingly highly organised campaign, there was little indication prior to election day that it would be able to secure widespread support from its nominally Muhammadiyah-based constituency.

Yet the Islamic parties have again confounded Indonesia’s pollsters. Remarkably, the Indikator survey released in the final days of the campaign underestimated the major Islamic parties’ vote by an average of more than 30%. Quite unexpectedly, the quick count results released in the hours following the election indicate that three of the ‘big four’ have improved their national vote shares, and that all four will be comfortably returned to parliament.

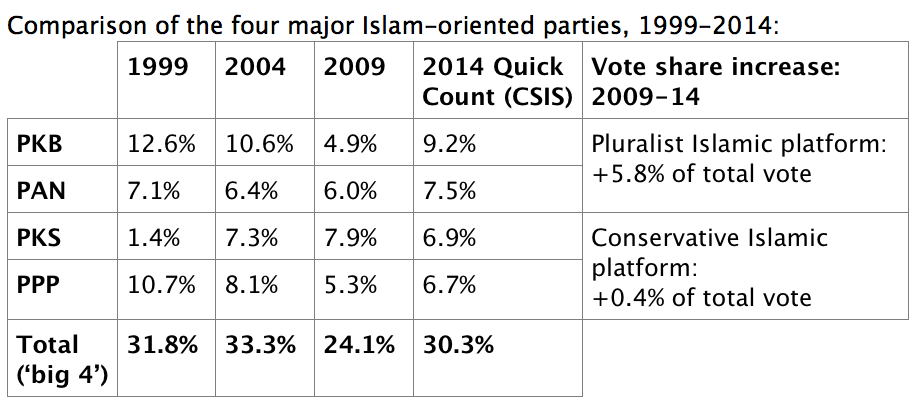

Only PKS has failed to improve on the vote share it achieved at the last election, yet given the turmoil faced by the party over the past year, a decline from 7.9% in 2009 to 6.9% in 2014 represents something of a triumph in damage limitation. The party often described as Indonesia’s best-institutionalised looks set to more than double the vote share forecast in the polls. PAN and PPP have made significant gains on their 2009 results, while PKB has come close to doubling its national vote share and, as predicted by Greg Fealy, has returned to its former position as Indonesia’s largest Islam-oriented party. If the 1.6% won by PBB is included, Islamic parties have come close to winning a full third of the vote at this election. Such a statistic hardly indicates the impending demise of these parties.

The table below examines the vote shares for Indonesia’s four largest Islam-oriented parties at the four post-New Order elections (note: figures not representative of total support for all Islamic parties).

PKS parliamentarian Hj. Ledia Hanifa Amaliah explained to me that survey data is often misleading when anticipating support for Islamic parties because urban Muslim voters are underrepresented in data samples. This explanation appears quite credible, given that this group of voters is generally identified as providing PKS’s support base, though the reasons for this irregularity are unclear. It may also be the case that voters who tend to be drawn to Islamic parties are more consistent in turning out to vote. The section of the population who do not cast a ballot (golongan putih / ‘golput’) certainly exceeds the proportion of respondents categorised as political non-identifiers in most survey data.

A more interesting question, however, is why these four Islamic parties have done so unexpectedly well in 2014. Several broad reasons for these parties’ success relate to the constellation of political parties standing at this election. First, the introduction of stricter requirements for parties’ participation at this election dramatically reduced the number of parties eligible to run at the national level, down to just 12 from the 38 which contested the 2009 ballot. The ‘big four’ no doubt enjoyed some benefit from the redirection of votes which had gone to Islamic microparties such as PKNU (National Awakening of Religious Scholars Party) and PBR (Reform Star Party) in 2009, though this alone would not account for the size of the upswing in their support levels.

A second, more persuasive, line of reasoning involves the collapse of the PD (Democrat Party) vote and the simultaneous resurgence of PDIP (Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle). It would appear that in 2009, many Muslim voters were attracted to SBY’s party because of its relative openness to Islamic political aspiration. Arguably, the PD position on the role of Islam within the Indonesian state is virtually indistinguishable from that held by PAN and PKB. Newer nationalist parties such as Gerindra (Greater Indonesia Movement), Hanura (People’s Conscience Party) and Nasdem (National Democrats) have ostensibly failed to tap into the Islamic vote as the ‘nationalist-religious’ PD managed to do. Meanwhile, PDIP has retained a secular-nationalist platform, consistent in its opposition to religiously-inspired legislative reforms, and is therefore a far less appealing alternative for Muslim constituents. With the decline of PD as a viable electoral vehicle, it is likely that many Muslim voters have chosen to return their support to Islamic parties. In the coming months it will be worthwhile evaluating the extent to which the larger Islamic parties have benefitted from PD’s electoral demise.

According to Ledia Hanifa, the factors underpinning PKS’s successful holding operation were the solidarity of the party’s cadre base and the willingness of its membership to turn out in support of the party. In the case of PKS, it may be that this high level of internal solidarity limited the potential for black campaigns and infighting between the party’s legislative candidates, as they sought to contest a limited number of available seats.

It is also clear that the Islamic parties – particularly PKS and PAN – were comparatively diligent during the election campaign. While travelling through Central and West Java during the weeks leading up to the election, it seemed to this writer that these parties’ flags, banners and posters had saturated many electorates to an extent unmatched by most other parties. Although it is not certain that physical advertising meaningfully correlates to ballot box support, the fact that PAN and PKS materials were commonplace in even relatively secluded villages seems to imply a well-organised presence at the grassroots level. While this is to be expected of PKS given its robust cadre network, PAN’s efforts are perhaps more noteworthy. If a pattern of strong grassroots activity was replicated across the archipelago, it may go some way to explaining these parties’ effective voter mobilisation on election day.

By re-establishing its ties to NU, PKB has once more been able to draw on the public support of that organisation’s elite, and secure access to influential kyai and their corresponding pesantren networks. As Muhaimin noted during a televised election night interview, the informal ‘open campaigns’ conducted by ‘dangdut king’ and PKB presidential hopeful Rhoma Irama, as well as rock star Ahmad Dani, have played an important role in attracting voters to the party’s events. PKS also benefitted from celebrity endorsement, with the hugely popular Sundanese comedian Sule appearing in party advertisements.

Thanks to the support of Abdurrahman Wahid’s widow, Sinta Nuriyah, PPP claimed the right to include the former president and NU chairman on certain campaign materials. The party also apparently benefitted from the shifting allegiance of some former PKS supporters, who had become disillusioned with that party’s pragmatic, ‘catch-all’ turn. Of course, PPP’s privileged status under the New Order means that its current leadership has inherited a well-established national infrastructure, and has been able to maintain lasting relationships with certain constituencies.

These are very much preliminary explanations for the strong showing by Islamic parties at the 2014 election, but they may go some way to clarifying how PAN, PKB, PKS and PPP were able to confound the pollsters so comprehensively. These parties will remain major players at the national level over the coming five years, and it looks likely that the former two, at least, will find a place in the ruling coalition which should be established by PDIP. Indeed, the anger of PPP members at Suryadharma Ali’s unilateral decision to lend his support to Prabowo’s presidential bid suggests that significant elements within that party also aspire to a place in government (whether PDIP will be willing to include PPP is another matter, of course).

Ultimately, this result confirms that Indonesia’s Islamic parties remain viable political entities, which cannot be written off lightly – regardless, it would seem, of polling results and survey data. In a variety of ways, PKB, PAN, PKS and PPP have done remarkably well at this election. How they use their electoral mandates to advance the interests of their loyal – even burgeoning – constituencies will provide their next challenge.

………

Thomas Power is a PhD candidate at the Department of Political and Social Change at the Australian National University. He is researching patterns of candidate recruitment and party institutionalisation in Indonesia.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss