Traditionally, constitutional courts constrain the popular will by holding elected politicians accountable to the constitution. In Indonesia, that dynamic is often reversed. As other scholars have noted, Indonesia’s legislature, the Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat (DPR), suffers from a democratic accountability deficit. Many MPs are not responsive to the will of the people. Corruption is endemic. Political parties lack clear ideological distinctions, depriving voters of a meaningful choice. By contrast, the Indonesian Constitutional Court has frequently come across as both more populist and more concerned with public opinion. In this article, I argue that even though the justices are not elected, there is strong evidence that they do respond to public opinion.

The Indonesian Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi) has nine justices, three each selected by the president, the DPR, and the Supreme Court. Justices serve for five year terms with the possibility of one reappointment. Individuals and organisations can submit petitions to the Court asking it to assess the constitutionality of national statutes. When the Court opened for business in August 2003, its success was by no means guaranteed. Chief Justice Jimly Asshiddiqie (2003–2008) recalls that it started from scratch (“mulai dari nol”), with hardly any budget or staff. The MK did not even have its own building. Moreover, the Indonesian government had a long history of ignoring the rule of law and subverting judicial independence. It was not unreasonable to worry about the new Court’s independence and willingness to rule against political elites in controversial cases.

Instead, during the past 15 years, the Mahkamah Konstitusi has become one of the most active and activist courts in Southeast Asia. During its first term, the MK revised 74 laws, annulled four completely, and nullified portions of another 23. Overall, the Court has granted around quarter of all petitions it received. Moreover, its decisions have had major political and economic repercussions. In some of its more prominent decisions, the Court has invalidated the privatisation of electricity utilities, struck down a ban on former Communist Party members’ standing for office, mandated an open party-list election system, abolished the natural gas regulatory authority, and condemned government budgets that failed to allocate sufficient funds for education.

Part of the explanation for the Constitutional Court’s success is its relationship with the Indonesian public. The Court’s popularity helped insulate it from political pressure: as Professor Donald Horowitz notes, the MK “built up a stock of political capital because of its apparent integrity and good faith.” Justice Maruarar Siahaan called public opinion “absolutely vital” to preserving the Court’s independence. Asshiddiqie claims public opinion was far more influential than any intimidation the justices faced from the executive branch, DPR, or the military. The Court’s reputation proved invaluable in 2011 when the DPR tried to amend the 2003 Constitutional Court law to circumscribe the Court’s jurisdiction. A coalition of law professors and activists promptly challenged the amendments before the MK, which declared them unconstitutional.

Strength in numbers?

At least some lawyers litigating before the Constitutional Court appreciate the Court’s desire for popularity, and have tried to leverage it to advance their claims. Some try to convince the justices that their legal claims have broad public support. One way they do so is by forming a large group of petitioners. For example, lawyers involved in a 2011 case challenging the appointment of political party members to the General Election Commission (KPU) believed that having a large coalition would convey the impression that the law had sparked widespread public outrage. They ultimately recruited 23 NGOs and 113 individuals to join the petition. They also made sure to include individuals and organisations from different parts of the country, including Java, Sumatra, Bali, Sulawesi, and Kalimantan. The Court granted the petition, accepting that the petitioners represented the public interest (kepentingan publik).

Alternatively, interest groups can try to convince the Court that public opinion actually opposes the petition by filing related party (pihak terkait) briefs (similar to amicus curiae briefs). For example, when a coalition of progressive activists challenged the Blasphemy Law in 2011, 18 Islamic NGOs filed related party briefs expressing their support for the law. These groups saw the law as a useful way to constrain unorthodox Islamic sects, such as Ahmadiyah. Notably, these groups argued that revoking the law would lead to interreligious conflict. The groups also attempted to frame their opposition as part of a mass movement in defence of Islam. The Constitutional Court ultimately rejected the petition, accepting the related parties’ argument that granting the petition might spark public discord.

In my dissertation research, I wanted to test the effectiveness of these strategies for utilising public opinion in constitutional litigation. I developed a statistical model including 483 petitions and 141 related party briefs submitted to the Constitutional Court between August 13, 2003, and October 2, 2013. I tested the effect of 1) the size of the petitioner coalition, and 2) the number of related party briefs against the petition on the probability that the Court grants the petition.

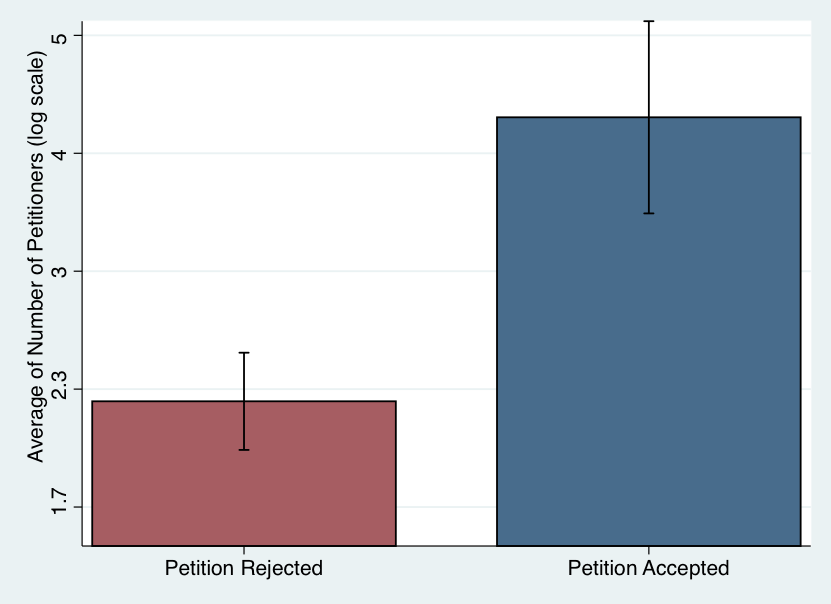

I find that signals of public opinion have statistically significant and sizeable effects on Constitutional Court case outcomes. In general, the Court is more likely to grant a petition if it is supported by a larger coalition of petitioners (see Figure #1).

Figure #1: Number of Petitioners & Case Outcomes. Number of petitioners is on a logarithmic scale. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

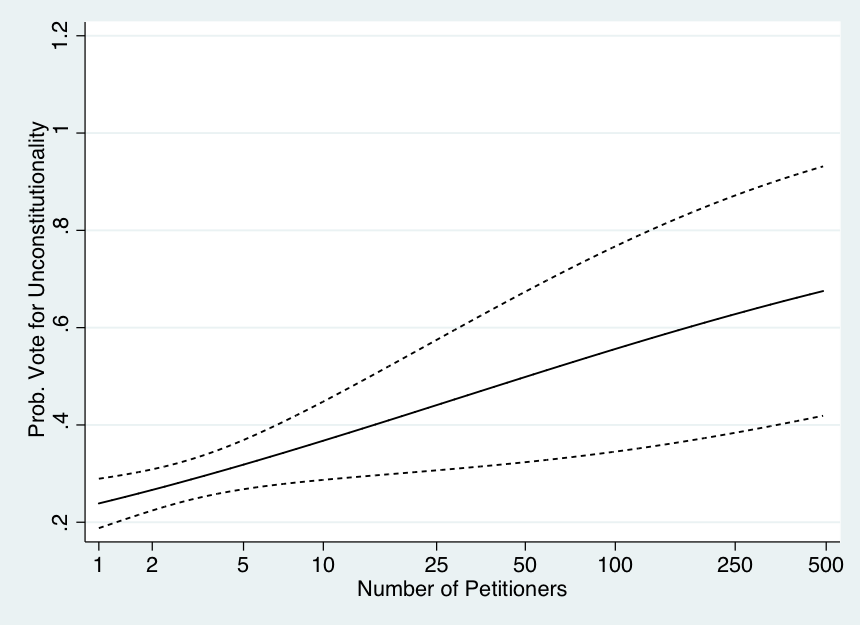

Increasing the number of petitioners in a case from 1 to 2 increases the probability that the Court grants the petition by 2.9% (see Figure #2).

Figure #2: Probability MK Grants Petition vs. Number of Petitioners Number of petitioners is on a logarithmic scale. The probability that the Court grants a petition ranges from 0 to 1. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

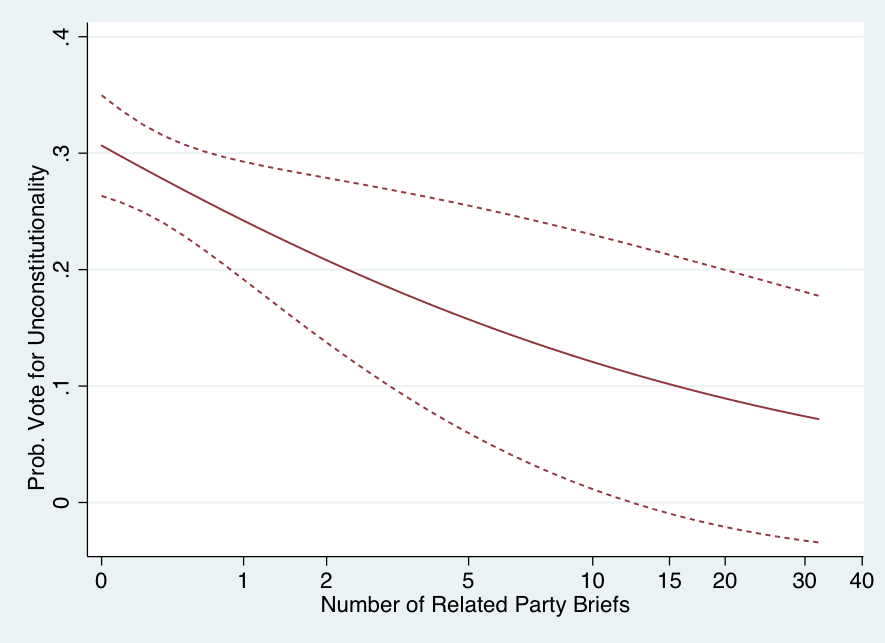

The effect is even larger for larger petitioner coalitions; going from 1 to 10 petitioners increases the probability of success by 13.8%. By contrast, related party briefs can counteract petitions. A single related party brief decreases the probability that the Court grants the petition by 6.6% (see Figure #3). This jumps to 15.2% if there are 3 related party briefs. In short, while public opinion does not explain all of the reasons why the Court might grant a petition, it definitely influences the justices.

Figure #3: Probability MK Grants Petition vs. Number of Related Party Briefs Against Petition. Number of related parties is on a logarithmic scale. The probability that the Court grants a petition ranges from 0 to 1. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

If the justices hoped that issuing popular decisions would enhance the Court’s legitimacy, they succeeded—at least partially. In a 2005 IFES survey, 68% of Indonesians aware of the Court approved of its performance, compared to just 11% who disapproved. Its net approval rating was significantly higher than either the DPR or Supreme Court’s. However, while citizens do care about the outcome of individual cases, they care even more about overall health of the institution. Thus, when the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) arrested Chief Justice Akil Mochtar in October 2013 for receiving over Rp60 billion in bribes, the Court’s approval rating dropped to just 28%. It recovered somewhat after successfully resolving Prabowo Subianto’s challenge to the 2014 presidential election results, but many activists now view the Court more sceptically.

A double edged sword

Concerns about the quality of Constitutional Court’s written opinions present another challenge to the MK’s legitimacy. Several legal scholars have expressed concerns about the thoroughness of the Court’s legal reasoning since 2008. According to Simon Butt, the

Indonesia’s minority report

Indonesian law recognises both international human rights norms and 'religious values'. The latter are increasingly taking precedence.

The results from my dissertation have several important implications for Indonesia’s Constitutional Court. First, even though they are unelected, justices do have clear incentives to heed public opinion because they rely on the public to act as a buffer against political elites. Second, it is possible to convince the justices that a petition has broader public support by forming a large coalition. Likewise, it is also possible to convey public opposition to the petition by filing related party briefs against it. Finally, any goodwill the institution accumulates from issuing popular decisions can disappear in the face of a scandal that throws its overall integrity into doubt.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss