Most domestic and international commentary on Indonesia’s 14 February elections has focused on the presidential race. But on the same day, Indonesians will also vote for legislators at district, provincial and national levels. Almost 10,000 candidates will compete for the national legislature alone, in what will be the country’s sixth legislative election since the collapse of Suharto’s authoritarian regime in 1998.

Legislative elections are a vibrant affair in Indonesia. The streets are plastered with campaign posters months in advance of voting day, candidates hold gruelling rounds of public events, and they develop sophisticated social media campaigns. Most candidates and their (often very large) campaign teams also invest huge financial resources into distributing patronage, handing out everything from rice and cooking oil, to clothing and cash.

Voter turnout is relatively high in Indonesia compared to the regional and OECD averages, and Indonesians express strong and consistent support for their democratic system and legislative elections. At the same time, the average voter is sceptical about political parties and about the national legislature too: when polled, Indonesians regularly place parties and the national parliament, the DPR (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat/People’s Representaive Council) at the bottom of a list of institutions they trust. (The military and the president usually come out on top.)

So what do Indonesian voters believe their legislators should be doing, and what kind of parliament do they really want?

As part of a broader project on political representation in Indonesia, we conducted a nationally representative survey in June 2023 that measured how Indonesians perceive democratic representation, and how they feel about the composition of the parliament, whether it represents ordinary Indonesians, and the work that legislators do. The survey interviewed 1,200 respondents face to face, with a +/-2.9% margin of error.

The results were striking: most Indonesians express strong support for a more equitable parliament, and for legislative work that focuses on programmatic policies over particularistic projects. Here we offer a brief snapshot of some of our findings.

Do voters feel their legislature is broadly representative?

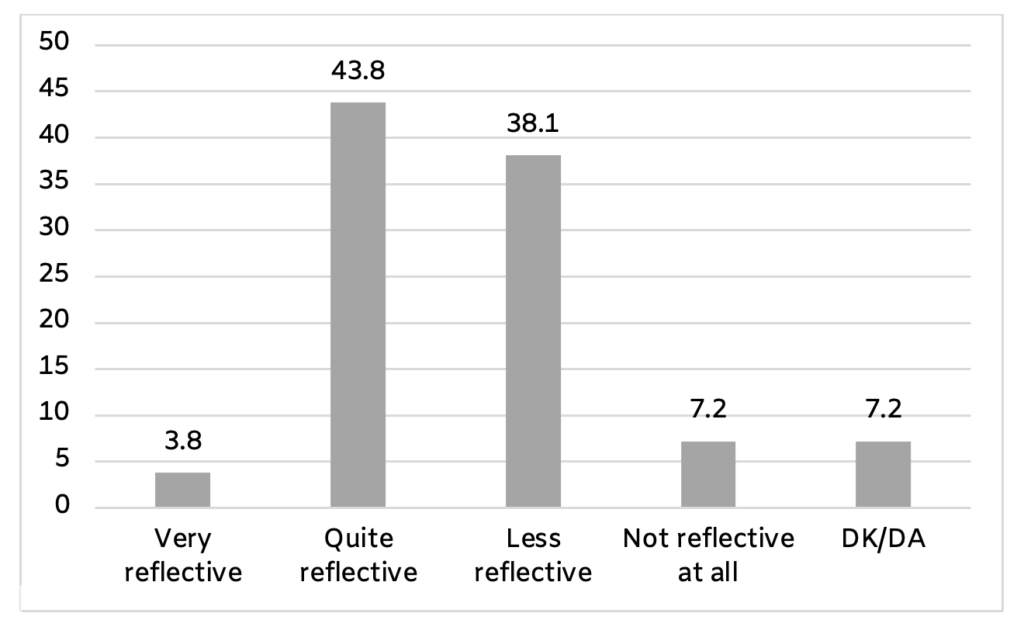

We began by asking respondents about the extent to which they feel elections are able to produce a parliament that reflects voters’ views and interests. Indonesians were divided: around 47% felt the parliament is broadly reflective of voters’ interests, and 45% disagreed (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Does the DPR reflect voters’ views and interests?

When we dug deeper into the data, we found that class indicators, and in particular education, were correlated with a negative view of the DPR’s ability to reflect voters’ interests. For example, almost 60% of university educated Indonesians, and over 65% percent of Indonesians in the top income bracket (i.e. over 4 million rupiah/A$400 per month) felt the parliament was not playing its representative role.

Ironically, most legislators have a background akin to those who are more likely to criticise them, i.e. they are more likely to be well educated, wealthy and from an urban area. As political campaigns have become more expensive in Indonesia, upper class candidates have come to enjoy a strong electoral advantage. Yet it seems lower classes citizens are more likely to feel parliament broadly reflects voters’ interests.

Mapping the Indonesian political spectrum

A new survey shows that political parties are divided only by their attitudes on Islam.

What do voters think legislators should be doing?

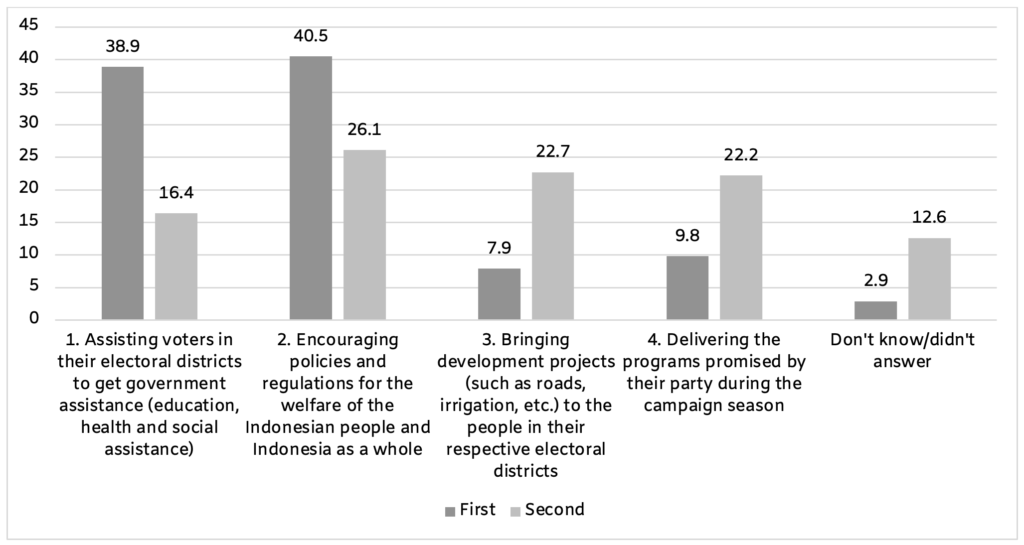

We then asked respondents what they believe are legislators’ two most important tasks. Each of the options were designed to reflect distinct ways voters might conceive of representation. Options #1 and #3 in Figure 2 (below) capture the notion that representatives should work above all to meet constituents’ concrete needs. We expect this to be a popular choice, because it reflects the clientelistic relationships that we know DPR members develop with their constituents in Indonesia. Options #2 and #4 capture a programmatic or policy-oriented understanding of legislative function and, in turn, representation.

Figure 2: What are legislators’ primary tasks? (Choose up to two)

Again the answers were varied, with respondents divided between seeing DPR members’ most important task as arranging government assistance for constituents, or seeing their primary role as encouraging policies and regulations for the welfare for the citizenry more broadly. Around a third of participants viewed development projects as representatives’ primary tasks, and a similar number believed their elected representatives should be delivering on parties’ programmatic promises.

What should the DPR look like?

What about the composition of the DPR? Do Indonesians feel that Indonesia’s key social groups are adequately reflected in the makeup of national parliament?

This question speaks to scholarly work that examines support for descriptive representation: the idea that voters want to be represented by members of their own group, whether that be based on gender, ethnicity, religion, class or some other identity category. Applied to the country as a whole, it suggests that the legislature should comprise a mix of individuals from such groups that mirrors the composition of the broader community: as a representative body, it should “look like” the country it represents. The logic is that political representatives who are themselves from a specific group will best advocate for that groups’ rights, interests and needs.

Our survey asked Indonesians a series of questions to gauge how important this form of representation is to them, and whether they wanted a DPR that looked different along descriptive lines. We asked them to agree or disagree to the following statements:

- In the DPR, only members of the lower to middle class (such as farmers or laborers) are able to effectively represent the views and interests of the lower middle class.

- In the DPR, only female legislators are able to effectively represent the views and interests of women.

- In the DPR, only legislators who are religious minorities (Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Confucians) are able to effectively represent the views and interests of minority religious group.

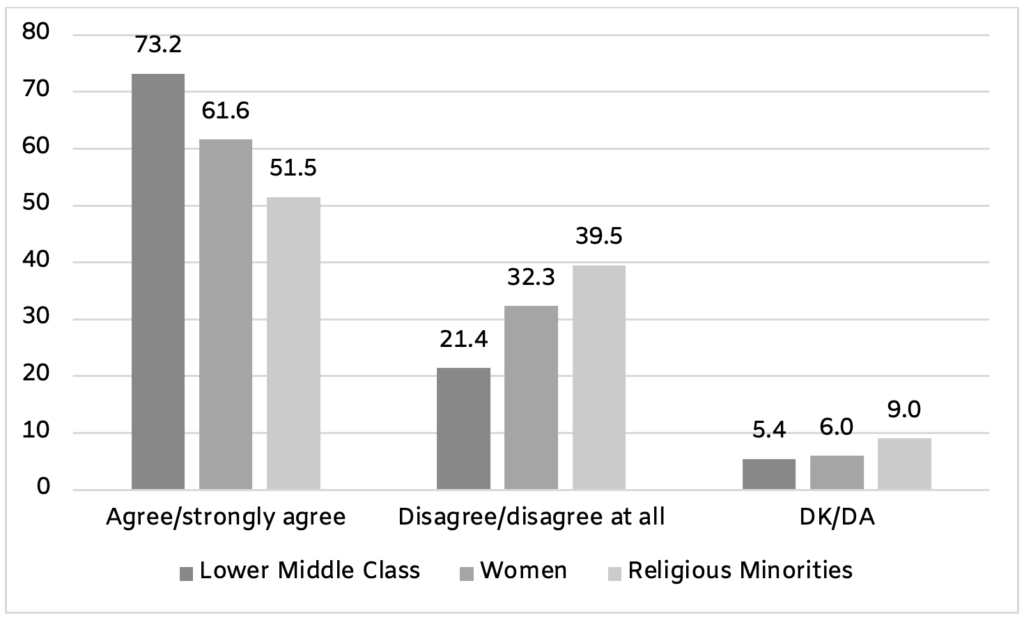

Figure 3: Descriptive representation

The results are striking: Indonesians overwhelmingly support the descriptive representation of class interests, which is noteworthy given that (as mentioned above) Indonesia’s national legislature consists of almost entirely upper class individuals whose occupational backgrounds are increasingly concentrated in the private sector.

The idea that only women can truly represent women also received strong support. When it came to religious minorities the responses were more divided, suggesting an ambivalence within Indonesia’s majority Muslim population toward to the idea that non-Muslims’ needs are best met through political representation.

As a follow up, we then asked whether respondents thought the number of legislators from these groups needed to be increased. The results again show very strong support for increasing the number of lower to middle class people in national parliament, with over 80% in favour, and for increasing women’s representation too. There is far less support for increasing the non-Muslim presence in parliament.

Figure 4: Increasing descriptive representation

Conclusion

Our survey suggets many Indonesians share a desire for a more egalitarian parliament, where lower class citizens and women are better represented. Indonesians also believe legislators should first and foremost be developing policies and regulations that serve the welfare of the population more broadly (although patronage-centred understandings of representation also have wide support).

This public atttitude contrasts with Indonesia’s current reality. Most legislators are wealthy, and many come to politics after a career in business, and use their political influence to further their financial interests. The rising cost of politics means such candidates have an electoral advantage, as do incumbents who can use government programs and parliamentary funds to support their campaigns. Despite potential underlying demand for change, there are few opportunities for this ‘supply side’ constraint to shift in the near future: barriers to entry for independent candidates are high, and political parties continue to seek well-resourced candidates who can underwrite their own campaigns.

And while our survey finds support for women’s representation, female candidates are less likely to have the economic resources needed to compete, and they face considerable headway from patriarchal attitudes holding that men are better suited to public leadership roles. Still, this unmet public desire for a different kind of legislature—one that includes a wider spectrum of people and interests—is significant and potentially more pervasive than either scholars or politicians have understood.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss