At the 2019 presidential election, Indonesia’s Islamist groups were at the peak of their influence. They banded together with Joko Widodo’s then rival, Prabowo Subianto, to orchestrate one of the most polarising presidential campaigns in Indonesia’s history. Though they have been battered by government repression since Widodo’s reelection in 2019, Islamist groups are now regrouping behind Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar in the 2024 presidential race.

In the course of my doctoral research into Indonesia’s Islamist opposition movements in the Jokowi years, I have been following Islamist activists, both virtually and on the ground, as they campaign on behalf of Anies and Muhamin’s candidacy. I have been struck by how much more timid these Islamist groups’ campaign rhetoric is compared with 2019. Gone are the days when their volunteers would go around from house to house to spread internet-sourced propaganda accusing their political rival of being a Chinese communist agent who was bent on abolishing Islam from public life and was conspiring to assassinate Muslim leaders—things they said about Jokowi in 2019. They no longer describe the election in apocalyptic terms, where one candidate is portrayed as an evil force while the other is hailed as the saviour that could salvage Indonesia from impending doom.

Instead, Islamist activists in Anies’ team and from affiliated volunteer groups have chosen to emphasise his commitment to what they call “ethical politics” (an Islamist euphemism for governance based in Islamic morality), his concrete achievements as governor of Jakarta between 2017 and 2022, and his promise to restore the freedoms and justice that have been eroded under Jokowi. Islamists’ campaign style, in other words, has shifted from being one characterised by passionate ideological agitation to a more level-headed programmatic style, reflecting the overall decline in ideological polarisation during Jokowi’s second term.

But does that mean that Islamists have abandoned their ideological beliefs and goals, or does it simply reflect political expediency? I argue that Indonesian Islamists’ rhetorical moderation is primarily an adaptation to the three key political realities of the late Jokowi years.

Firstly, state repression has made Islamists cautious about embracing overtly sectarian campaigning. Secondly, with Islamists having aligned behind the candidacy of the Anies and Muhaimin, and keeping their options open with a reconciliation with Prabowo Subianto in a potential second round of the presidential election, they have sought not to alienate pluralist Muslim voters linked to traditionalist groups like Nahdlatul Ulama (NU).

Third, unlike in the aftermath of the mass mobilisations against the alleged blasphemy of former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, there isn’t a religiously-charged issue around which a dynamic of polarisation can arise. The issues of Rohingya and Israel–Palestine conflict have featured in the 2024 campaign, but these issues do not divide Indonesians neatly along Islamic–nationalist lines, and offer only limited potential for the reactivation of ideological passions in the short term.

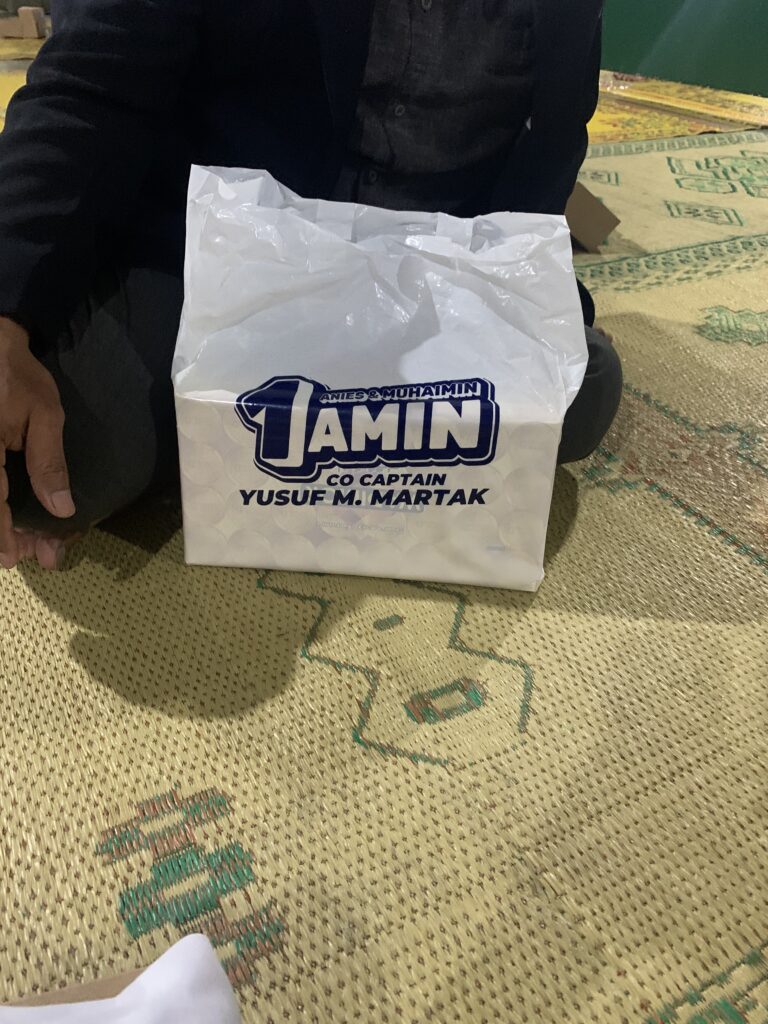

Promotional materials for a campaign event for Anies Baswedan featuring prominent Islamist cleric and “co-captain” of Anies’ campaign team, Yusuf Martak (left)

De-risking religious rhetoric

I limit my analysis to non-violent Islamist groups such as FPI—relaunched, after the ban of the Front Pembela Islam/Islamic Defenders’ front in 2020, as the Front Persaudaraan Islam/Islamic Brotherhood Front—and the self-styled “Alumni” of the 212 movement activists that led the protests against former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama in 2016–17. These groups share relatively moderate goals and methods compared to jihadist extremists. They pursue an Islamisation of society and the state not via revolution but through gradualist tactics like proselytisation, education, social services, advocacy, and political participation. They will enthusiastically drum up intolerant sectarian sentiments (which they genuinely hold) when it benefits them, but remain ready to tone it down when their survival is at stake. For this community of non-jihadist Islamists, the goal is to win power first, then work on the religio-political reform later.

In 2024 as in 2019, direct engagement in electoral politics is part and parcel of this strategy. On 27 September 2023, Anies and Muhaimin visited the FPI leader Rizieq Shihab, as if to secure his blessing, just before they officially registered their candidacy. Once Anies’ candidacy was confirmed, he recruited Yusuf Martak, a close confidant of Rizieq, as one of the co-chairs of his success team.

Islamists have made it clear that they are not giving a blank cheque to Anies. In exchange for their support, they required Anies and Muhaimin to sign a 13-point “Integrity Pact” which, among other things, affirmed the candidates’ commitment to back the Islamist agenda of combatting secularism, communism, and religious blasphemy (for them, a code word for the perceived growth in the power and “arrogance” of Indonesia’s Christian minority). The agreement also stipulated that Anies and Muhaimin would enforce public morality based on Islamic norms and improve ordinary people’s economic circumstances by stopping a purported inflow of mainland Chinese workers.

Following the same formula as in 2019, in November 2023 FPI and its affiliates organised a Conference of Religious Scholars (Ijtima Ulama) in order to give their choice of candidate the stamp of religious authority. The 2023 Ijtima resulted in a religious recommendation by “Grand Imam” Rizieq Shihab to vote for Anies and his running mate Muhaimin. The idea is to leverage the grassroots network of FPI and the Brotherhood of 212 Alumni (Persaudaraan Alumni 212, or PA212) to organise campaign activities and the distribution of campaign materials in support of Anies. As of late 2023, the resurrected FPI boasted branches in 23 out of 38 provinces, while formal PA212 structures have been established in all districts in the 10 most populous provinces; both sped up their expansion of local branches with a view to mobilising voters for the 2024 election. That said, it is unclear how many members either organisation actually has—local FPI activists often double up as PA212 executives.

Although the “Integrity Pact” between FPI and the Anies campaign and the Ijtima Ulama’s endorsement of Anies exhibit some of the sectarian and xenophobic tone that characterised Islamist activism in the 2019 election, my on-the-ground observation of FPI-linked campaign events suggests they have cooled down their divisive religious narratives for 2024.

A typical campaign in Central Java, for instance, would attract between 50 to a few hundred people, though the number might be higher in FPI strongholds such as Banten and Greater Jakarta. Many such campaign events that I observed were simple (held in mosques, Islamic pesantren boarding schools, or other free venues) and mostly funded by volunteers and donations from local candidates seeking to win the sympathy of Islamist constituencies. Attendees at these events receive free T-shirts, posters, mugs and other merchandise, but I have not witnessed any exchange of monetary gifts (as has been reported in other candidates’ campaigns). This is not surprising given Anies has reported the lowest amount of campaign funds among the three presidential candidates.

What was more striking to me was the relative lack of religious zeal and apocalyptic narratives that were ubiquitous in 2019. Speaking at a pro-Anies volunteers meeting in Solo on 9 January, the secretary general of PA212 Uus Solihuddin told the volunteers to de-emphasise lofty ideology and focus more on concrete programmatic policies. Whereas in the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election Islamist leaders relied on intimidation and fear-mongering to coerce Muslims to vote for Anies (such as threatening to not perform funeral prayers for recently deceased Muslims who supported “infidel” candidates), Islamists are now carefully avoiding any statements that can be construed as smear campaign, misinformation or sectarian incitement. As PA212’s secretary-general instructed the assembled volunteers,

Stay clear of black campaigns! Focus on promoting the vision and mission of Amin (Anies and Muhaimin), make it viral by using plain, easily accessible language. Don’t talk about lofty ideas. Just talk about cheap groceries (sembako). Because let’s face it, most Indonesian people are not at that [intellectual] level yet. Engage the people by saying things like: do you want better healthcare? Do you want cheap electricity? Do you want a driver’s license that applies for a lifetime—no need to renew it every five years? Then you can reinforce the message by telling them that these are the recommendations of our ulama who have signed an agreement with Anies.

The caution around “black campaigns” reflects Islamists’ fear of persecution and arrest, a critical factor that explains the shift away from sectarian narratives. (Alfian Tanjung, another Islamist cleric who was present at the meeting in Solo described here, had been imprisoned from 2017 to 2020 after being convicted of criminal defamation for calling Jokowi and PDI–P “lackeys” of the Indonesian Communist Party/PKI).

SAFEnet, an NGO that advocates for freedom of online expression, reported in 2022 that the arrest of opposition activists under Indonesia’s Electronic Information and Transactions Law (UU ITE) has increased by 26%; most were charges with defaming state officials and institutions. Islamists are arguably the most targeted category of all opposition activists. The fact that Rizieq Shihab is on parole until June 2024, following his release from prison in July 2022, is a living reminder of the great risks they are facing: as one activist put it, “any tiny mistake could send Habib Rizieq back to prison, that’s why we need to be careful.”

Yusuf Martak similarly told a group of pro-Anies volunteers in Klaten and Solo that they should emphasise his concrete achievements in combating social ills in Jakarta, such as closing down a major brothel and a restaurant chain that gave free promotional beers to anyone named Muhammad. It was suggested that promoting his accomplishments in public morality and infrastructure development would be more effective and less risky than invoking overtly Islamist jargon (e.g. “infidels”, “shari’a”) that are closely associated with radicalism.

Maintaining moderate support

Last but not least, Islamists felt compelled to tone down their religious zeal in order to appease the moderate, traditionalist Muslim base of Anies’ running mate, Muhaimin Iskandar.

The costs of repressing Islamists

The banning of FPI or any other “anti-Pancasila” group is not a shortcut to ending deep-seated discrimination against minorities.

Many within Muhaimin’s NU milieu perceive Anies as a “Wahhabi”—a reference to the ultrapuritan brand of Sunni Islam associated with Saudi Arabia, which has become a slur among Muslim moderates in Indonesia—due to his modernist background and close relationship with the Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera/PKS). This is in the context of an internal rift within NU: the organisation’s chairman Yahya Cholil Staquf and most of its national board have sided with Prabowo, while influential NU kyai (traditionalist religious leaders), including NU’s former chair Said Aqil Siradj, have backed Muhaimin and his party PKB. In East Java, a number of kyai from Yahya’s camp exhorted their followers to not vote for Anies, saying that he secretly conspired with the banned transnational organisation Hizbut Tahrir and FPI to replace the Indonesian republic with a caliphate.

To allay those suspicions, FPI and the 212 activists have included references to “the preservation of the Unitary Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) and Pancasila” in their Integrity Pact with Anies. In fact, FPI and PA212 have followed a trend set recently by government agencies and NU institutions of beginning their formal gatherings by singing the national anthem.

Anies shaking hands with his supporter, former NU chair Said Aqil Siraj at a commemoration of the birthday of NU cleric KH Bisri Syansuri, Muhaimin Iskandar’s great grandfather, Jombang, 12 January 2024 (Photo: author)

Islamists are also calibrating their campaigning with a view to the possibility of reconciling with Prabowo Subianto, with some leading figures in FPI and PA212 already planning to shift allegiance to Prabowo should Anies fail to enter the second round. As one senior activist from FPI put it:

We are now campaigning for Anies, yes. But we shouldn’t attack the other side overzealously. I don’t think it’s right to throw a smear campaign at Prabowo. After all, he and [his party] Gerindra have done a lot for us. Anies promised us lots of things, but in the end he gave more money and positions to NU. Despite Prabowo’s betrayal, it was Gerindra politicians who defended us, gave us legal assistance when our members got criminalised. Gerindra advocated for the KM50 cause [the police shootings of 6 FPI members in 2020] in parliament. So we shouldn’t offend Prabowo too much, he’s our best option if there is a second round.

Palestine and Rohingya offer limited scope for polarisation

Anti-Rohingya incitement has intensified on social media since late 2023. One video that went viral on Tiktok purported to show how Rohingya asylum seekers in Aceh threw away food that had been donated to them by local villagers. Another alleged that Rohingya asylum seekers in Malaysia had demanded land, warning viewers that they might want to take over local people’s land in Aceh too. This online incitement culminated in an incident in which hundreds of university students in Aceh raided a refugee shelter and forced the Rohingya to leave. Rights activists and social media experts contended that the online hate speech was too systematic to be organic; the newspaper Koran Tempo quoted a source who stated that some elements within state security forces hired the student mob in order to sow crisis.

Some Islamist groups believe that a backlash against Rohingya asylum seekers has been engineered to discredit Islamists, who had long conducted humanitarian fundraising for Rohingya victims of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. The online content that has framed Rohingya as lesser Muslims with sinful habits was therefore like a slap in the face to Islamists.

While it remains mysterious how the anti-Rohingya campaign came about, or who was behind it, the issue has become a point of contention between the presidential candidates. Anies has struck a sympathetic note, saying that Indonesians have a humanitarian duty to help Rohingya Muslims who have come asking for protection. Prabowo, on the other hand, has asserted that it is unfair to impose such a burden on Indonesia, and that the United Nations ought to be responsible. Ganjar Pranowo, meanwhile, has given a vague comment that neither accepts nor rejects the asylum seekers.

Some pro-Anies Telegram channels have spread a counter-narrative that the Acehnese student leader who coordinated the attack on Rohingya was a youth member of Prabowo Subianto’s Gerindra party, and that Prabowo has sanctioned the discrimination against one of the world’s most persecuted Muslim minorities. The Rohingya issue has not flared up significantly, with the government swiftly providing an alternative shelter for those displaced by community protests in Aceh.

The Palestine issue has meanwhile become fertile ground not only for Islamists’ electoral campaigning but also for their long-term expansion and recruitment. The issue is also a “safe” one, because the government is more tolerant of Islamist mobilisation on foreign conflicts—especially given Indonesia’s official support for Palestinian freedom—than local ones. In December 2023, for the first time in five years the government allowed FPI to hold the 212 Reunion Rally at Jakarta’s Monas square, on the condition that it was focused on Palestine.

Some Islamist sources told me that when their pro-Anies events were prohibited by PDI-P district and village heads in rural West Java, for instance, they got around the restrictions by conducting a Palestine solidarity roadshow. They said that even some PDI–P strongholds could accept them and were willing to donate money if the clerics focused on the plight of Palestine and offering religious counselling to the villagers. Many lay PDI-P sympathisers volunteered their phone numbers to Islamist clerics after being told that they could get free online counselling and unlimited supplies of “holy water”, only to find themselves bombarded with Anies campaign materials through WhatsApp. The Palestine issue remains significant for Islamist revival beyond the election, having wide appeal that cuts across partisan cleavage, and it provides Islamists with ample opportunities for fundraising and outreach to new audiences.

In Indonesia’s outer islands, however, the Israel–Palestine conflict carries more divisive potential. On 25 November 2023, violent clashes broke out between the Muslim Solidarity Front (Barisan Solidaritas Muslim) and a Christian group named Manguni Brigade in Bitung, North Sulawesi. BSM was holding a pro-Palestine rally on the street when they ran into a convoy of Makatana Minahasa Christians who were also on their way to a cultural parade. Some of the Christians carried Israeli flags, which triggering an altercation with BSM that devolved into a brawl that killed one person and injured two others.

In video footage that circulated on social media, several people from Manguni Brigade dressed in traditional war attire were seen chasing BSM members; a number of local Muslims joined another fight that broke out in the city centre later that night. The video footage also showed the Manguni Brigade burning Palestinian flags and destroying an ambulance that belonged to BSM. Islamist online channels quickly spread the videos and talked about jihad against the “Christian Zionists”. Rizieq Shihab also issued a statement demanding that the government punish the Zionist supporters who attacked Muslims in Bitung.

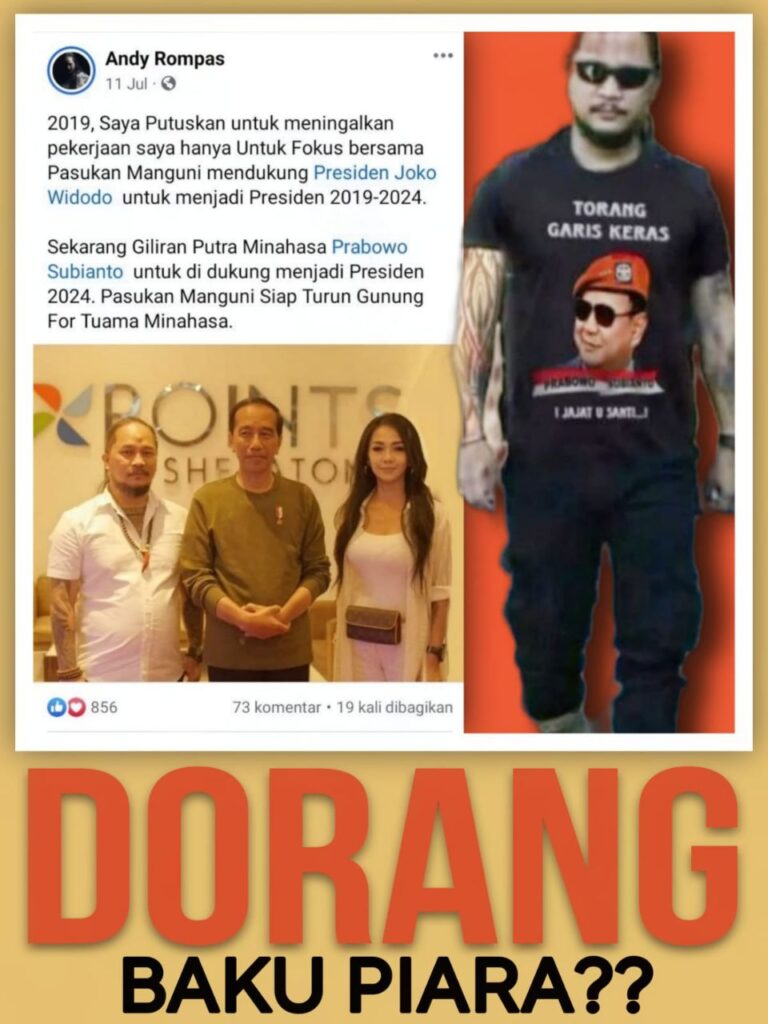

While the local conflict was swiftly managed by local authorities, its effects have lingered and bled into the election. Pro-FPI social media accounts circulated pictures of the Manguni Brigade leader wearing a Prabowo T-shirt; in one picture, he was seen posing with Jokowi with the caption in the version shared by Islamists remarking that “this is the reason Manguni Makasiouw isn’t banned after causing riot in Bitung, likely protected by Jokowi”. Another video showed a big Israeli flag being waved at a PDI–P rally for Ganjar Pranowo. In Central and West Java, some Islamist activists have been preparing to deploy their Laskar (security or paramilitary organisations) to guard polling stations against intimidation and fraud they allege is being planned by the “pr o-Zionist red thugs” (preman merah, a reference to PDI-P’s party colours).

Islamist online propaganda on Laskar Manguni (Source: Telegram channel monitored by the author)

Despite Islamists’ attempts to use the Rohingya and Palestine issues to activate the latent sectarian tensions in Indonesian society, the debate around these issues do not neatly slice the electorate along the Islamist vs pluralist lines. In the case of Israel–Palestine conflict, Indonesians regardless of their religious inclinations are overwhelmingly pro-Palestine. The issue is not as divisive as in the West. The anti-Rohingya issue has to some extent taken on a political turn, with Anies’ Islamist supporters advocating the rights of Rohingya refugees, while Prabowo has cast them as a potential threat to Indonesians’ economic interests. As Prabowo said while visiting Aceh on 24 November 2023: “now let’s say we want to help the Rohingya. How can we help, our own people are short of food. Around 20% of our children are malnourished.”

These two issues are therefore unlikely to cause deepening polarisation. However, the Palestine issue particularly provides a fertile ground for Islamists to revive and expand their appeal (not least because the government tolerates Islamist propaganda on foreign rather than domestic affairs), hence its usefulness will outlast the election.

Anies–Muhaimin campaign merchandise, featuring the name of “co-captain” Yusuf Murtak (Photo: author)

Conclusion

My observation of the election campaign in urban and rural Java reveals a much calmer picture than the previous presidential race. Unlike in 2019, people did not complain as much about an emotionally draining election, marked by identity politics, that affected their personal relationships with family and friends.

Islamist groups themselves have decided to “cool down” divisive campaign narratives for various strategic reasons—without necessarily abandoning their long-term ideological agenda. This has partly to do with the importance of not alienating the moderate traditionalist Muslims, especially in East Java, that form an important part of the Anies–Muhaimin ticket’s electoral coalition. The stigmatisation of radicalism has also contributed to Islamists’ strategic avoidance of ideological messaging. Indeed, Jokowi’s anti-radicalism policy and counter-polarisation efforts by NU and other pluralist groups have pushed Islamists to the fringe, at least for the time being. Moreover, Islamists have seen that Jokowi’s social assistance programs have contributed to his high approval ratings, fostering a belief that Indonesian people care more about their economic wellbeing than ideology—hence the Islamists’ pivot to bread and butter issues when campaigning for Anies.

Finally, the lowering intensity of ethnoreligious tension and partisanship suggests that post-election riots like those seen in May 2019 are unlikely. However, the violent Christian–Islamist clash in Bitung reminds us that there is potential for isolated local conflicts between supporters of different candidates in the lead up to the election and its aftermath.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss