The past year or so has seen conspicuous setbacks to Indonesian democracy’s capacity to protect many social rights, including of some of the more vulnerable members of society—most notably women, religious and sexual minorities, and victims of the 1965–66 mass killings. Ironically, this has occurred under a government whose declared agenda of extending access to social services has been a celebrated and defining characteristic, not to mention the presumption that its establishment had deflected a prior possible reassertion of authoritarian-like politics.

By 2015, a wide-ranging survey had offered the proposition that Indonesia’s hard-won democracy had stagnated. However, many of the more sombre assessments of this condition were to come in the wake of the second round of the Jakarta gubernatorial election in April 2017, and the farcical blasphemy case that saw the defeated Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (“Ahok”) sentenced to jail. The mood of these analyses could not be more different from the upbeat tone that characterised those that immediately followed the victory of Ahok’s close ally Jokowi over Prabowo Subianto in the 2014 election. That result had spared most Australia-based analysts—and many of the people of Indonesia—from the pain of having to contend with what might have been an overwhelmingly clear signal of democratic regression.

But the manner of Ahok’s downfall is merely symptomatic of much deeper problems within Indonesia democracy, which have never been resolved since the fall of Soeharto. These problems are intertwined with continuing oligarchic dominance and the manner in which intra-oligarchic conflict now occurs. The mobilisation of identity politics has become a more salient feature of conflicts over power and resources. In fact, we may be entering a new phase in which conservative takes on Islamic morality, and the hyper-nationalism which is being positioned against them, become the most important cultural resource pools from which the ideational aspects of intra-oligarchic struggles are forged—thus accentuating the illiberalism of Indonesian democracy. Indeed, the relative absence of organised social forces that would drive an agenda of liberal political reform is more palpable than ever before.

Islamic mobilisation and oligarchy in Jakarta

The race for the Jakarta governorship provided some of the best indications of how continuing oligarchic domination relates to the growing prominence of the illiberal characteristics of Indonesian democracy. Undoubtedly the most socially divisive local election in Indonesian history, it was even more hotly contested than the 2014 presidential contest, which was already considered exceptionally polarising by a number of analysts.

Ahok had been widely regarded as an able governor. But his fateful words about the Koranic verse Al Maidah 51 came to position him, effectively, as the co-author of his own political demise. The mass mobilisations against him combined calls for Islamic solidarity with a familiar narrative about the systematic marginalisation of the ummah. This narrative has been long entwined in Indonesian modern history with the perception that Indonesia’s ethnic Chinese minority has disproportionately benefitted from preferential economic treatment since colonial times. One irony, of course, is that these anti-Ahok demonstrations appeared to be supported by the children of Soeharto, whereas it was their father’s own New Order regime that had been responsible for nurturing the giant ethnic Chinese-owned conglomerates in Indonesia in the first place by providing them with political and economic protection. The implication of members of that family in the protests indicated that matters of oligarchic conflict were far from being entirely separated from the events surrounding the fall of Ahok.

The two most widely discussed interpretations of Ahok’s defear have been provided by Ian Wilson and by Marcus Mietzner and Burhanuddin Muhtadi. Wilson has emphasised how Ahok had created antipathy among the poor residents of Jakarta, mainly by pursuing urban rejuvenation projects that involved the eradication of entire slums. Mietzner and Muhtadi, however, argue that Ahok’s loss was more plainly related to religion: an aversion among many voters to back a non-Muslim and the belief that the governor had indeed committed blasphemy against Islam. Neither explanation is completely dismissive of social-economic issues on the one hand, or religious identity issues on the other—so there is little point in accusing either side of being unaware of the interrelatedness of the matters at hand.

But a somewhat different—though not necessarily incongruous—interpretation would place his defeat more firmly within the evolution and mechanics of broader conflicts within Indonesia’s oligarchy. All three candidates in the first round of the Jakarta polls had essentially served as proxies for competing coalitions of entrenched elites. Ahok represented the ruling coalition driven by the PDI-P. Anies Baswedan competed as the candidate of a bloc led by Prabowo’s Gerindra Party. And it is difficult not to construe Agus Yudhoyono’s sudden foray into the political arena, necessitating the abandonment of a promising military career, as anything less than an attempt to forge a political dynasty on the part of his father, SBY, founder and leader of the Democratic Party.

If this sort of interpretation has any merit, Ahok’s defeat in the face of FPI-led mobilisations was less an indication of the inexorable rise of Islamic radicalism in Indonesian politics than of the ability of oligarchic elites to deploy the social agents of Islamic politics for their own interests. The broader implication is that radical expressions of Islamic identity—which go together with rigidly conservative interpretations of Islamic morality championed by the FPI and similarly hard line groups—are being increasingly nurtured and refashioned within the present requirements of oligarchic politics.

In fact, by facilitating expressions of frustration by many ordinary citizens through the use of a predominantly religious-tinged political lexicon, Indonesian oligarchic elites have all but ensured that Indonesian Islamic politics would move increasingly toward a conservative direction. Moreover, it is instructive that the resultant social and political conservatism is being mainstreamed with the aid of oligarchic elites who would not be normally considered the social agents of Islamic politics.

In the aftermath of the Jakarta election, many took to warning that it signalled the rise of such religious extremism, which presents an immediate threat to Indonesia’s pluralist social fabric and to its internationally praised democracy. In a way, such fears represent a revisit of older concerns, expressed during the early years of reformasi, that democracy would result in the political ascendancy of Islamic radicalism, which had supposedly been suppressed only because of the iron-fisted rule of Soeharto. Indeed, Indonesians who tend towards secular forms of democratic politics should be aware, now more so than ever, of the historical and contemporary weakness of politically liberal (or social democratic) streams within Indonesian politics.

The hyper-nationalist reaction

Given the long absence of Leftist traditions as well from the scene—since the violent destruction of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) in the 1960s—it has become increasingly clear that the most durable bulwarks against hard line Islamic politics are to be found within strains of nationalist politics. The problem for Indonesian democracy is that these strains are typically entwined with social interests embedded within the apparatus of the state, including the military, that have been more historically concerned with social control than social representation.

This point is crucial in understanding the significance of Jokowi’s response to the newly-assertive Islamic mobilisation. It is expected that the same tactics of mobilising identity politics against Ahok will be employed against him, though perhaps in not exactly the same manner or degree of effectiveness. There is already much rumour-mongering in social media about Jokowi’s personal background and history that casts Indonesia’s president as a closet ethnic Chinese communist. In spite of their somewhat fantastical nature, it is apparent that the president himself has become quite concerned about the swirling rumours surrounding his identity. At the very least, he has become sufficiently irked to deliver an irate rebuttal and to describe them as nothing less than a politically-motivated attack on his character.

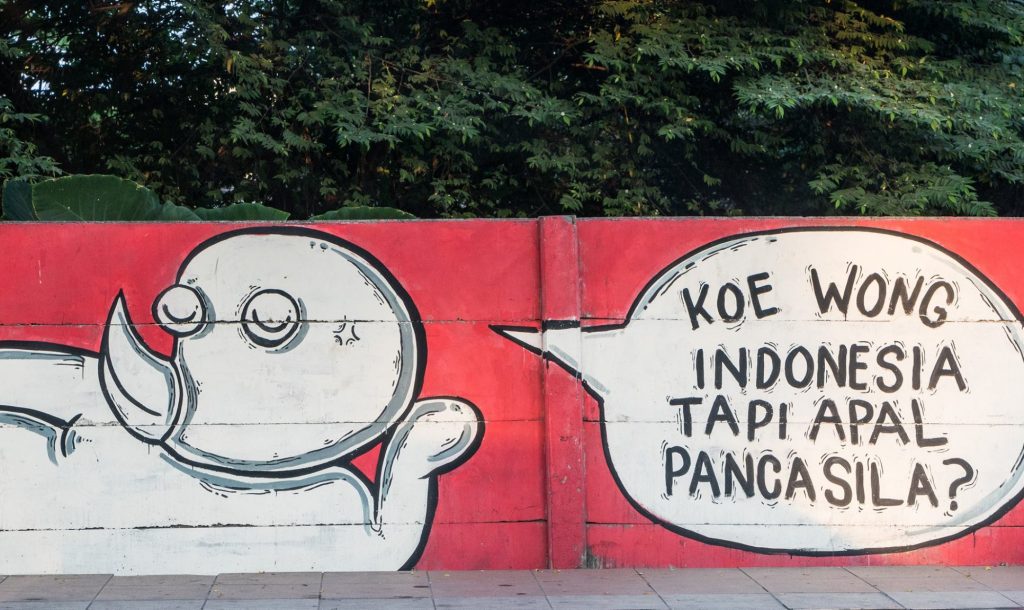

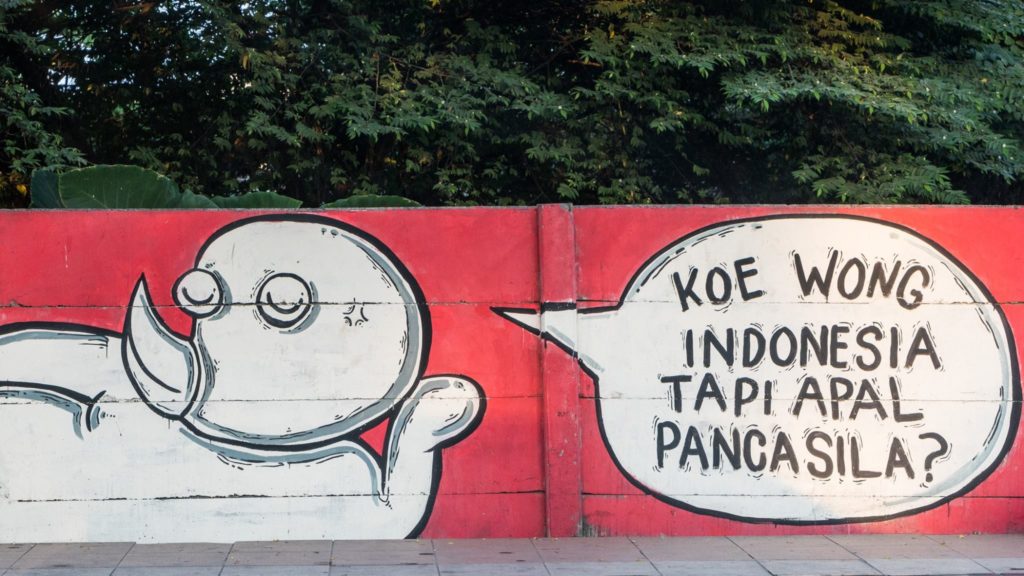

In policy terms, Jokowi’s main reaction has been to deter such rumours by promoting the cultural symbols associated with Indonesian nationalism. He has done this, for instance, by way of initiating a new national holiday—Pancasila Day—on 1 June. The sanctity of the Unitary State of Indonesia (NKRI), based on the founding idea of “unity in diversity”, has been emphasised quite conspicuously as well in his speeches and public comments since Ahok’s defeat. He has even vowed to demolish organisations that are anti-Pancasila, in the kind of forceful terms that would not have been out of place in the heyday of the New Order.

It is not surprising that the president has felt compelled to deliver a response designed, at least in part, to buoy those Indonesian citizens who would be wary of a democracy that unwittingly opened the door for the ascendancy of conservative Islamic morality. There is some delightful irony in the fact that FPI leader Habib Rizieq Shihab has been investigated by the police for an indiscretion prosecutable under a wide-ranging anti-pornography law, which his organisation had heavily supported at its inception. This is the case even if political liberals should possess awareness that the pornography law is essentially as inane—from the point of view of democratic rights—as the blasphemy law that had brought down Ahok.

Nevertheless, banning the FPI altogether carries political risks for a president expecting to be attacked on the basis of his own questioned Islamic credentials. Instead, Jokowi landed a symbolic blow on an Islamist enemy via the Perppu (regulation in lieu of law) enacted in July 2017. This decree paved the way for the government to ban, without judicial process, organisations deemed to be undesirable, with Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) being the first target as expected. As part of the ban, university lecturers who are known to be members of the organisation have been threatened with expulsion from their jobs, giving rise to fears of a broader government instigated witch hunt. Even critics of Islamic hard line groups have warned that the government is embarking on an anti-democratic “slippery slope”.

The bigger picture: oligarchy, Islam, nationalism?

The political dynamics being witnessed speak to larger points about how oligarchic power has had the capacity to change in relation to new circumstances, and therefore, to evolve. As the Indonesian oligarchy is much more decentralised in nature today than during the pinnacle of the New Order, competition among its factions over power and resources has taken place largely via the institutions of democratic governance. It is in the context of such contests that appeals to conservative ideals of morality—whether Islamic or nationalist—may become a more entrenched rather than just fleeting feature of Indonesian democracy. This is because such appeals have the potential to connect otherwise detached oligarchic elites to broader bases of social support, by at least temporarily obscuring actual divisions within Indonesian society through moral appeals, but without being linked to any kind of agenda of transformation of the way in which power is constituted.

As I and other scholars have argued, the New Order-nurtured oligarchy reinvented itself in the course of the struggle over the direction of reformasi. It did so by colonising the institutions of Indonesian democracy—its parties, parliaments and elections. This was assisted, in turn, by the endemic and systematic disorganisation of civil society sustained by decades of rigid and often brutal authoritarian rule. The consequence was that social forces effectively representing politically liberal or social democratic alternatives were almost nowhere to be seen in the crucial early years following the fall of Soeharto. Leftist ones had of course been long obliterated.

As discussed above, the primary form of pushback to the rigid and inflexible Islamic conservatism has been a similarly retrogressive hyper-nationalism, which references the inviolability of the Indonesian Unitary State (NKRI) and the state ideology, Pancasila. This is so even if that state ideology has proven to be quite pliable throughout modern Indonesian political history, utilised somewhat differently (in different contexts) by presidents Soekarno and Soeharto. Indicative of the basically retrogressive nature of this response is a new proposed arrangement by the Minister of Home Affairs whereby the rectors of Indonesian universities would be chosen by the president, as a means of ensuring that Islamic radicalism does not grow unabated in university campuses due to tacit support from some within the higher ranks of academia. Of course, the problem with such an arrangement is quite similar to the one surrounding Perppu No. 2 2017; it could be used potentially to stamp out other kinds of “threatening” ideas in the future, such as those connected even to mainstream political liberalism. Already, university students have been warned by a military luminary of the dangers of “liberalism, communism, socialism and religious radicalism”, all of which he facilely categorised under “materialist ideology”.

In other words, it is not hard to imagine that the establishment of hyper-nationalist barriers to Islamic radicalism will have quite authoritarian effects, certainly in the medium to longer term. It also encourages rigid conformity to a set of values and ideas—in this case associated with rigidly organic-statist definitions of Pancasila rather than to a religion—to which democracy activists were opposed during much of the New Order period. Among these was the notion of society where the pursuit of self-interest was supposed to be contained by a state embodying the common interest—but which in fact helped to insulate a particularly predatory form of capitalism from potential challenges emanating from civil society. In line with this sort of development has been the promotion of the Unit Kerja Pembinaan Pancasila (Work Unit for the Cultivation of Pancasila), which presents an eerie reminder of New Order-style so-called P4 courses, wherein people from all walks of life used to be indoctrinated to the state ideology through mind numbing mandatory classes. Yet embarking on similar exercises is now somehow accepted by many as a progressive step, rather than a nod to the intrinsic conservatism and suffocating insularity of earlier organic-statist tendencies in Indonesian political thought and practice.

Long-time democracy activists in Indonesia will find it particularly disconcerting that present circumstances have made it so easy for the commander of the Indonesian Armed Forces (TNI) to declare—and not for the first time—that democracy contradicted the principles of the state ideology of Pancasila. It goes without saying that the general concerned, Gatot Nurmantyo, was not lamenting the prevalence of money politics or oligarchic domination. Instead he was lambasting the actual practice of voting, which in his view, inhibited another practice—that of consensus-building—deemed more in keeping with an essentialised notion of what constitutes an authentic Indonesian culture. Though not surprising given its source, these kinds of comments inevitably bring back uncomfortable memories of the suffocating nature of New Order political discourse, which frequently quelled dissent by labelling it as inherently “foreign” or un-Indonesian. In fact, there is a real danger that liberal—let alone more Leftist critiques of the way that power is constituted in post-Soeharto Indonesia—will be increasingly susceptible to a similar kind of labelling, whether by reference to the sanctity of the values of Pancasila or those considered to be of divine origin.

The new populist currents

One final point needs to be made. This relates to the increasingly attractive idea that populist politics has come to make its mark on Indonesian democracy. There has been much discussion of the rise of populism in Indonesia since the 2014 presidential elections—from authors such as Ed Aspinall, Marcus Mietzner, William Case, and myself with Richard Robison—in which the two candidates were widely seen to be making use of populist rhetoric. But apart from the “outsider” status claimed by both, which has been one focus of attention, a major characteristic of populism is that it attempts to “suspend” difference, albeit temporarily, among sections of society to bring them behind a particular political project. In other words, there is a penchant within populism for supposing homogeneity in the face of actually growing social heterogeneity, largely by juxtaposing the fate of the many and pure against that of the few and morally corrupt.

References to members of an ummah who have in common the experience of systemic marginalisation since colonial times, can form the ideational basis of an Islamic form of populism, whereby the downtrodden and pious are juxtaposed against rapacious elites. But given the organisational incoherence of Islamic populism in Indonesia, the binding of people to Islamic vehicles is less achieved by maintaining their loyalty—for example through the provision of material benefits by way of access to social services, as has been the case in parts of the Middle East—but through continuous efforts to sustain controversy.

Nationalist forms of populism, which are more conventional in the global sense, relatedly aim to define a “people” who are the repository of virtue as well, in contrast to evil and rapacious elites, including foreign ones. In Indonesia, it is sustained in part by reference to supposedly authentic and immutable cultural values that allegedly value harmony, which may become under siege by a range of influences, including potentially that of radical forms of Islamic politics.

What we may be effectively witnessing in Indonesia is therefore a newer phase within which political conflict increasingly relies on the employment of different variations (and combinations) of religious and nationalist forms of populism, and where political liberalism and Leftist critiques are effectively as side-lined as they had been in the authoritarian New Order.

Indeed, in the case of Indonesia, social groups that had been assumed—especially within the paradigm of modernisation theory and its associated more recent and sophisticated manifestations—to be the harbingers of socially and politically liberal values have in fact never displayed such a sociological characteristic very strongly. Richard Robison had already emphasised the conservatism of the Indonesian middle class and bourgeoisie of the 1990s, developing as they had within an authoritarian social order where the fear of uncontrolled mass politics was systematically cultivated. Thus, in dubbing Jokowi the “middle class president”, Jacqui Baker is reminding us that the president’s “illiberal tendencies… are not qualities of the man per se, but symptomatic of the Indonesian middle class and the unique political conditions under which it was formed”.

Some of this conservativism, reshaped within a new social and political context, is now being expressed through world views sustained by references to Islamic morality or hyper-nationalism. These can be linked to ways of asserting modes of political inclusion and exclusion that are detrimental to the rights of the more vulnerable members of Indonesian society. Significantly, the process of further political illiberalisation is being facilitated no less than by the evolving imperatives of oligarchic domination and the mechanics of intra-oligarchic competition over power and resources within Indonesian democracy—something for which there is no obvious institutional remedy.

…………………………

This an adapted version of the author’s paper presented at the 2017 Indonesia Update conference at the Australian National University, which will be published in full in the December edition of the Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies.

Vedi Hadiz is Professor of Asian Studies and Deputy Director at the Asia Institute, University of Melbourne. An Indonesian national, he received his PhD at Murdoch University in 1996. His research is in the broad areas of political economy and political sociology and covers Indonesia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Among his books are Islamic populism in Indonesia and the Middle East (Cambridge University Press 2016), Localising power in Indonesia: a Southeast Asia perspective (Stanford University Press 2010) and, with Richard Robison, Reorganising power in Indonesia: the politics of oligarchy in an age of markets (Routledge 2004).

Images in this post courtesy of ANU’s Ray Yen.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss