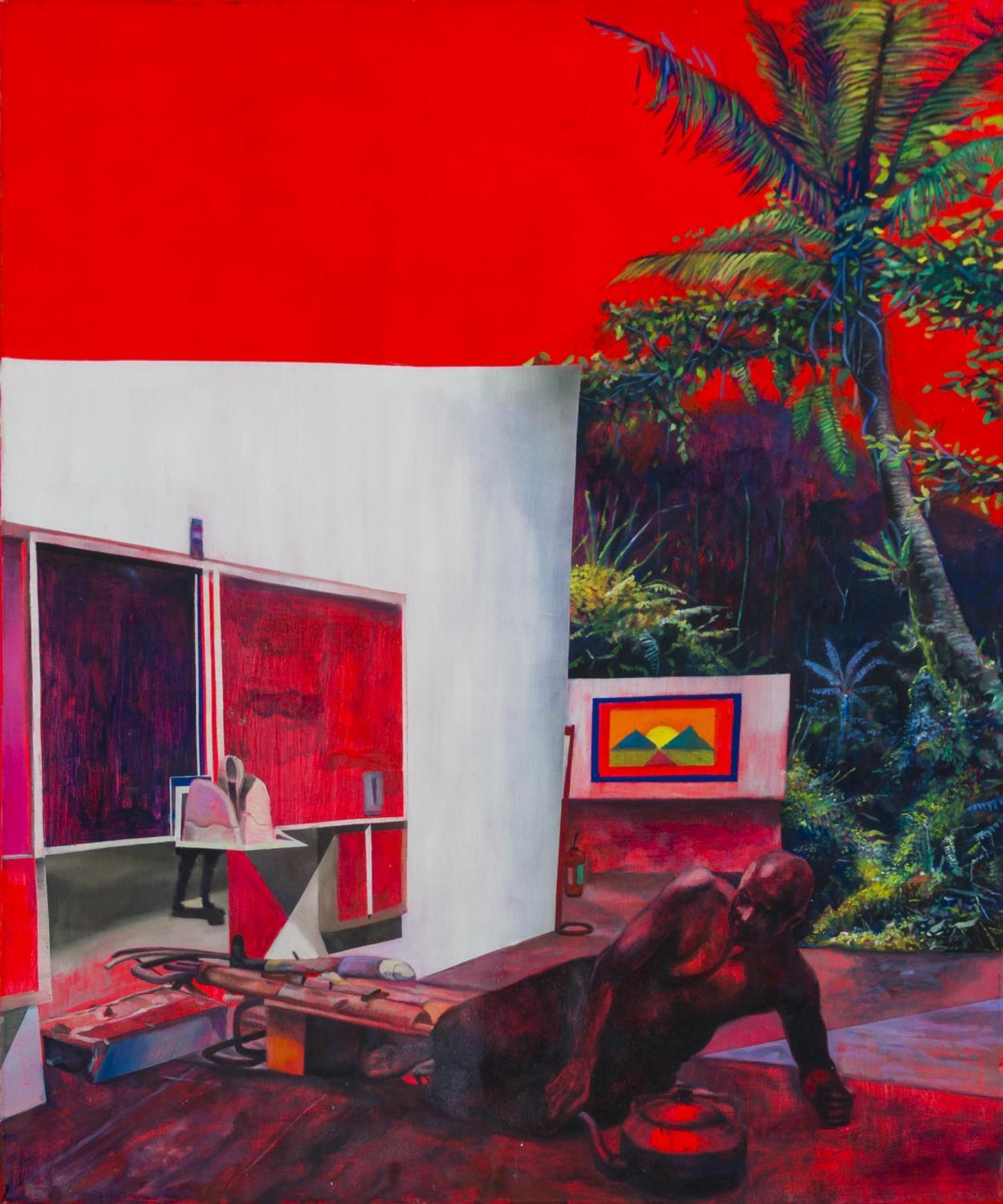

‘An Artworld Disturbed by Java man (After Raden Saleh)’, 2018, by Zico Albaiquni (b.1987, Indonesia). Oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 120 x 100cm. Image courtesy the artist and Yavuz Gallery.

Gaining a place at the Asia Pacific Triennial (APT) at the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) has been a significant milestone in the careers of many Indonesian artists. Although they were already well known in art circles, the first exhibition in 1993 helped launch the international careers of several artists including Heri Dono, FX Harsono and Dadang Christanto. Christanto’s mesmerising performance at the original APT opening is still widely remembered as a significant high point in contemporary art. Globally recognised artists like Arahmaiani, Mella Jaarsma, Eko Nugroho, Hahan and Tintin Wulia have all exhibited in the APT at different times. Even as the APT has gradually expanded its geographical scope to include South Asia and the Middle East, Indonesia retains an important place in the hearts of curators and the art-going public.

At the 9th APT, Indonesia is ably represented by five artists: Zico Albaiquni, Aditya Novali, Elia Nurvista, Handiwirman Saputra and Boedi Widjaja. This relatively modest selection covers a lot of artistic ground. At a time when women are arguably under-represented in Indonesian art’s international forays, it includes one female artist. It also stretches from Bandung to Solo by way of Singapore and West Sumatra and includes artists of varied ethnic heritages working in vastly different styles. The APT curators have clearly tried to capture the pluralism of Indonesia’s contemporary art. Their selection successfully reflects the breadth, dynamism and novelty of the Indonesian art scene.

However, given the proliferation of contemporary art in Indonesia, the APT curators have unfortunately had to leave a lot of significant artists and ideas unrecognised. One hopes that the upcoming Indonesian exhibition, Contemporary Worlds: Indonesia (21 June–27 October 2019) at the National Gallery of Australia will go some way to remedying this for Australian audiences. In the meantime, despite the obvious quality of the exhibition, it seems appropriate that the APT does not claim to have judged the best the region has to offer. Rather, it sensibly presents itself as a profoundly eclectic affair that encourages visitors to think hard about the possibilities of art outside of national frameworks.

The work of the included Indonesian artists is so divergent in purpose, style and concept that it is difficult to judge their relative merits. However, if one measures the quality of art by how long it engages an audience, then Solo-based artist Aditya Novali’s spectacular installation “The Wall: Asian Un(real) Estate Project” (2018) is one of the standout works of the whole exhibition. Structured as a dark counterpoint to the kind of models used to sell real estate in shopping malls across Asia, “The Wall” renders the audience voyeurs as it invites them to peer through over 100 separate windows into tiny cell-like apartments. Within each apartment, unique tableaux suggest all kinds of human desperation and degradation. The work beautifully juxtaposes the humour and pathos of contemporary urban life.

On the other hand, if one values art for how much it makes one think about art itself, then West Sumatran artist Handiwirman Saputra’s curious sculpture “Manahan bentukan” (“Holding formature”) might take the prize. Although it seems to originate more from a modernist concern with the possibilities of the medium, rather than a contemporary concern with lived experience, the work is inspired by concepts drawn from Minangkabau linguistic and cultural forms. Saputra is well known as a member of the Yogyakarta-based Jendela Art Group, who have been as controversial in the Indonesian art world as their abstracted and formalist approach has been popular with collectors. Eschewing political and social themes, Saputra takes both a globally well-trodden and refreshingly innovative path towards the question of materiality.

Also expressing a deep interest in form and taking architecture as its impetus, Singapore-based but Solo-born artist Boedi Widjaja’s installation “Black-Hut, Black Hut” (2018-19) embeds and integrates itself into the gallery like no other work in the exhibition as a structural amendment to two floors of gallery space. It also effectively explores the idea of the trans-regional or post-national that is becoming increasingly common in contemporary art discourse. Described as a “proto-structure”, the work extends the gallery into a new physical and conceptual space that resonates with influences as diverse as a Queenslander house, a Singaporean HDB block, the Surakarta Kraton and the artist’s childhood home in central Java. Reflecting on the idea of home, it simultaneously invokes a feeling of stability and a sense of the precariousness of place the artist must have experienced growing up as a trans-located Chinese child.

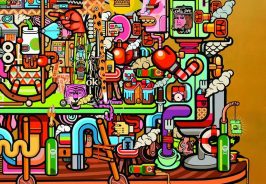

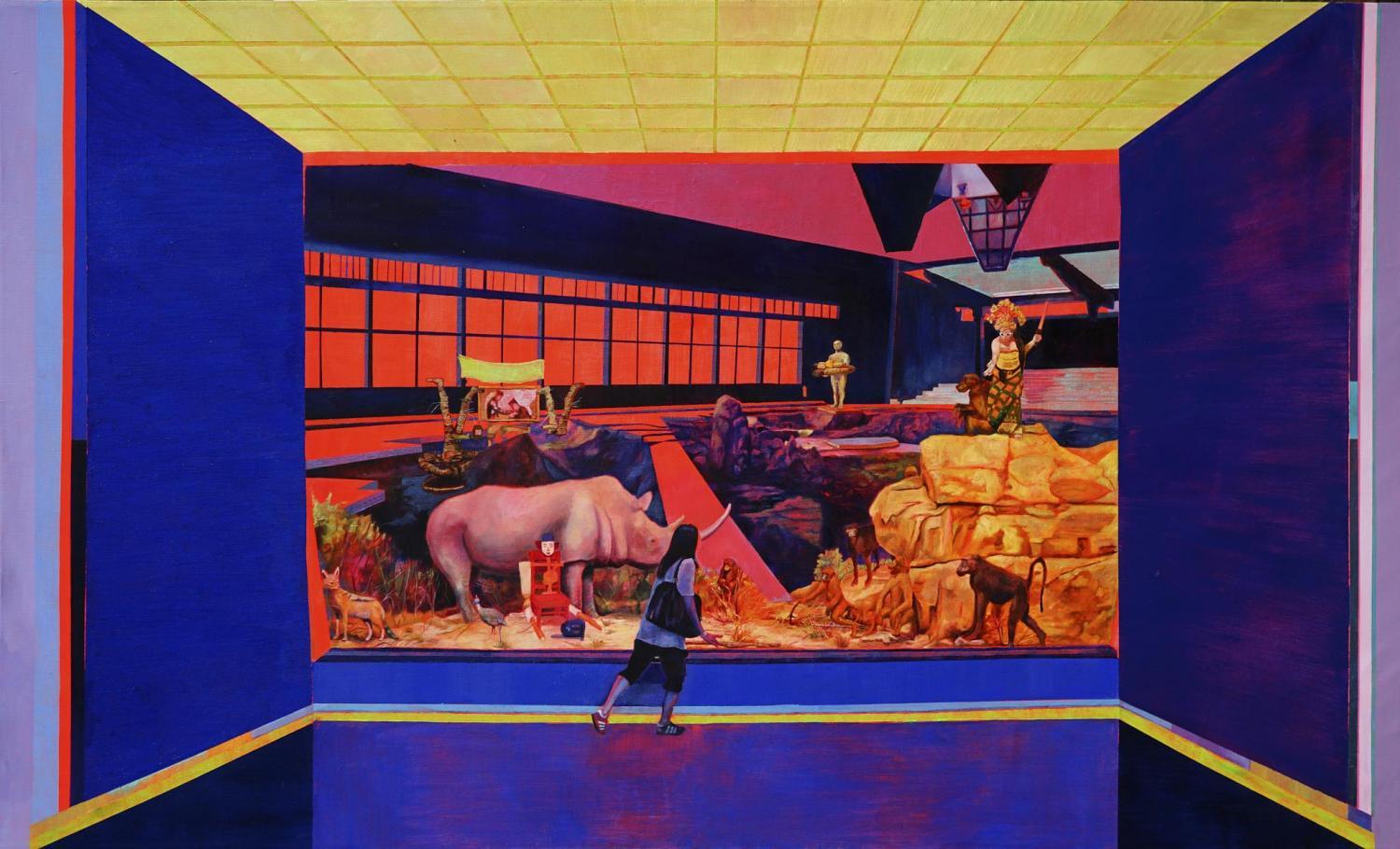

The somewhat more didactic work of Yogyakarta artist Elia Nurvista will be appreciated by those who believe that art should be both critical and pedagogical. Combining a mural with small multicoloured vase- or vessel-like sculptures made from sugar and organic resin, “Sucker Zucker” (2018) continues a longstanding and extensively researched theme for Nurvista in which she explores the destructive nature of the sugar industry through a postcolonial lens. The bright pink background of the mural helps her work stand out as one of the most overtly political in the exhibition. Her period-style cartoons of slave-like workers being cowed by whip-wielding overseers leave little unsaid and in acknowledging her using the increasingly common artistic practice of having anonymous artisans help produce her work, Nurvista opens up important questions about art and agency in the present day. In previous projects, Nurvista smashed her sculptures and invited the audience to taste them and appreciate their internal bitterness. Sadly, in this version, the assumed requirements of the APT to retain the work foreclose on the engaging sense of crisis and revelation that powerfully illuminated her earlier and more dynamic efforts in other venues.Bandung artist Zico Albaiquini’s paintings, which adorn the cover of the APT catalogue, are a revelation of the Indonesian artworld itself. Defying genre boundaries, his somewhat lurid works invoke Indonesian art history while embodying its disparate and decidedly non-linear trajectory. Using a quasi-realist style occasionally splashed with a sense of the abstract expressionism that never really took firm root in Indonesia, Albaiquini incorporates references to major Indonesian artworld figures in a way that invites endless speculation about his view of Indonesian art history. His work is highly symbolic, and I spent some time pondering the connection between a foregrounded rhino and a diminutive but armed Arahmaiani. In a way Albaiquini greatly expands Indonesia’s representation at APT. By my count, he shares his place with the spirit of Raden Saleh, AD Pirous, S. Sudjojono, Dede Eri Supria, FX Harsono, Heri Dono as well as Arahmaiani.

Zico Albaiquni, b.1987 Indonesia: “When it Shook–The Earth stood Still (After Pirous), 2018. Oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas / 120 x 200cm—Courtesy the artist and Yavuz Gallery

Seen across its entire 25-year history, the APT has done more than any other institution to bring Indonesian contemporary art to a global audience. With only five artists, this 9th edition effectively channels the spirit of the Indonesian contemporary art world. Although each of the included artists is already highly regarded, it will be interesting to watch how their careers develop in Australia following their increased exposure in APT. Despite the fact that Indonesian contemporary art is still under-appreciated in Australian collections, previous APT editions have always resulted in increased interest amongst our public institutions and private collectors. With a growing number of smaller exhibitions in the offing around the country, like the marvellous “@perempuan” show currently in Melbourne and the upcoming “Termasuk” show in Sydney, as well as the NGA show looking to be quite spectacular, one hopes that this interest will continue to grow.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss