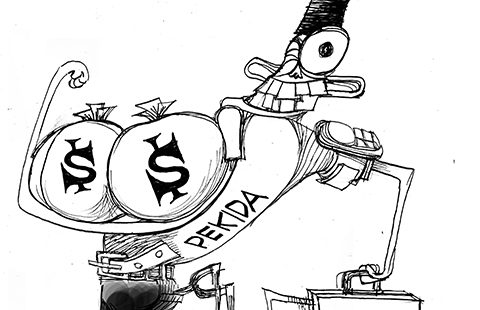

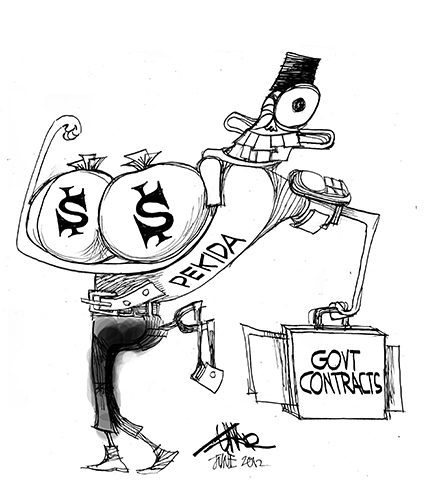

Image by Malaysian cartoonist and satirist, Zunar.

In the wake of a brawl in Kuala Lumpur’s Low Yat Plaza, Sophie Lemière looks at how youth, prejudice and mob violence go hand-in-hand with politics.

The Malay word amuck or amok (rage) is the most famous Malaysian export along with palm oil (praised by Nutella lovers) and rubber (praised by everyone). Amok or to run amok has become a global concept to describe any sudden and ephemeral acts of violence to a killing rage. There is no cultural specificity here; we have sadly seen people running amok from Columbine in the USA to Paris and the beaches of Sousse (Tunisia).

Amok is surely the only Malay word the entire world uses, without even knowing its quasi-mystical origins. Anthropologists, psychiatrists and novelists have written extensively on this word, exploring the linguistic roots of amok to the intricacies of a psycho-pathological phenomenon; an unresolved intellectual quest well resumed by Yan Kon[1]. The “pengamuk”, the one who suddenly falls into a violent frenzy, was once seen as a hero: a mystical warrior getting his inner strength from god. Malay mysticism and history is filled with epic stories of such great warriors. Today, that heritage may be found in the hybrid tradition of Silat balancing an intense physical practice and mystic-religious beliefs with prayers to invulnerability charms[2]. Sadly today, for most, the pengamok has lost his nobility and is seen simply as a psycho.

This linguistic-mystic maze is now used to describe a non-event: the rowdy gathering of about 200 people at the empire of electronic goods, Low Yat Plaza in Bukit Bintang (Kuala Lumpur’s entertainment district), following the alleged theft of a mobile phone and consequent brawl.

Would it make sense to point out that those gathered were mostly young Malaysian Malays and that the Low Yat Plaza shops were owned mostly by Malaysian Chinese? As the police said: “no violence”, “everything under control”, “nothing racial”. Sure. The gap between the descriptions we are reading in the press and the police statements are echoing the illusion. Of course there is nothing racial when a group of young men run amok over allegations of theft of an expensive hand phone.[3] The pride of the men involved may definitely be higher than the price of the bloody phone. This is not racial but universal.

But when a group of angry people demonstrates in front of the very same building in support of the alleged angry petty thief calling for “justice”; one may wonder the reason why, if not racial, they would do so? But again, in Malaysia, where political parties are “race-based”, where the national identity card states ones religion, where some get more than others because of a slight genetic differences (that may be solved by religious conversion though!), where members of parliament are urging some of their fellow citizens to go back to their great-great-great-great-great grandparents’ country, and where certain national leaders claim their ethnic membership before their citizenship[4], we need to understand once and for all that there is nothing racial, and even less racist in Malaysia. Indeed, everything is political.

The pengamok here might not be the one we think. As we know, in Malaysia, politics have for long run amok, and at a faster rate than the people. The Low Yat Plaza’ craziness which naturally pleases the media and scares Malaysian mothers and tourists is far from being an isolated or irrational phenomenon. It is the symptom of a well-orchestrated system. Between Amok and Politik lays the rationality of Politok.

Politok in action

Politok is a system where the idea of “prejudice” – dividing “us” and “them” is nurtured at every level of society. This rhetoric is widely spread by majoritarian ethno-nationalist organisations and ethno-centric political parties. All society’s “wrongs”, from economic disparities to homosexuality, are simplified to the extreme and unattended but always explained by the same idea: “some” have stolen the wealth and the land, “they” threaten culture and religion, “they” have imported drugs and prostitution, so “we” must “resist”. In Europe, “they” were the Jews in 1930s, “they” were Italians in the 1950s, today “they” are the Romas, the Muslims, the refugees and so on. “They” are always the minority, a convenient punching bag to channel the frustrations of the ethno-centric majority. In Malaysia, the culture of “prejudice”, and all its attached concepts – justice, revenge, resistance, power – is used as justification for political, sociological and economical behaviour from which emerge populist state policies to “uplift” the so-called “prejudiced group”.

The myth of prejudice in Malaysia

The myth of resistance and prejudice has nurtured many young Malaysian Malays. It begins with the teaching of a distorted version of Malaysian history systematically erasing a large part of the country’s multi-ethnic heritage[5] and instilling political propaganda. Every individual experience is then perceived through the prism of this myth around which one builds their vision of the world.

Moreover, the discrepancies existing between what young Malays are made to believe as “a genuine and sovereign people” of the land and what they can actually achieve – limited by a poor educational system – in a highly competitive job market is significant pressure and frustration.[6] We are here only unveiling one aspect of a schizophrenic system leaving aside repressions of sexuality, lack of religious freedom, media censorship and self-censorship, political repression of opponents, corruption of government leaders and so on.

Political scientists generally fear the emotional parameter and avoid it in their research as if political behaviours were only made of “dependent” and “independent variables” and other jargons and agonising analytical tools. The use of violence such as demolishing or burning religious sites or instigating riots to alter political behaviour, and where insurgents (acting on their own or on the behalf of a third party) know their actions will generate a reaction from a targeted population is widely recognised. Nevertheless political scientists rarely explain the reason why these behaviours change.[7] Emotions are clearly relevant to politics, and in this case they are central.

Anger, frustration, pride… to fight this prejudice, “conscious Malays” choose to join a political party or a ‘non-governmental organisation’ (NGO). What best than an organisation of one’s own to defend ones community’s interests? It is for that very simple reason, that some young Malays join Pekida: to defend the Malays.

In a system where the redistribution of the wealth follows scrupulously the lines and orders of the patronage system, it seems for many that hard work and education is not the required skills. And here lies the second motivation of the youthful members of Pekida: to build a network in a desperate attempt to correct a failed system. The switch from NGO activism to political action and violence then is an easy one. Within a short span of time, young members feel empowered by a quasi-sacred mission to protect their own, and to restore justice at any cost or almost.

Pekida and politics in Malaysia

Pekida is a “non-profit” and “non-governmental” religious organisation. The organisation and its link to the political sphere were first revealed in August 2014 by the Malaysian press when the police orchestrated the biggest and most mediatised crackdown on gangs ever made in Malaysia. Soon, the alleged links between the ruling party and gangs leaders affiliated to Pekida were discarded and on several occasion UMNO leaders have renewed their support of the organisation.[8]

Pekida claims officially 50,000 members, but this figure does not include the underground groups whose leaders mostly claim allegiance to the ruling party. Pekida members are for most, Malaysians (and registered voters). There has not been any investigation on Pekida groups or other Malay NGOs for their activities in the same manner that the Registrar of Societies is now targeting Christian organisations, but again remember there is nothing racial. Several groups of individuals claiming their membership to Pekida are involved in political demonstrations and episodes of violence; they are connivance militants offering their services to political parties in exchange for money or favours. The collusion between underground network and politics, selling your muscle for “work” or political violence is among the oldest jobs in the world. Preman in Indonesia, Mafiosi in Italia, Yakuza in Japan, the entrepreneurs of violence have many names.

The leadership of Pekida perpetually denounces the existence of deviant branches, and claims non-responsibility in outburst of violence: irresponsible indeed. Surprisingly, the organisation has never been under any investigation nor has it tried to re-name itself. To be clear, the ambiguous nature of Pekida, its link to the political arena, the service rendered to UMNO during political campaigns and the potential violence of its members is old news.

But the visibility of the potential for violence of disenfranchised youths that join the ranks of Pekida is what should attract attention. Indeed, the question is how to channel the frustration of disenfranchised youths bored outside of the busy election time? And when side incomes and rare state allowances are insufficient to open the golden doors of Low Yat Plaza?

Disenfranchised youth to connivance militants or entrepreneurs of violence out of job; all the symptoms of a dangerous system. Again the pengamok might not be the one we think. The study of Yak Kon, finally mentions that other suggested causes of amok include: febrile delirium, tuberculosis, syphilis, epilepsy and opium intake. A thorough study of the entire Malaysian system and its leaders would then require a rather funny and difficult data collection.

Meanwhile keep calm and amok on!

Sophie Lemière is a political anthropologist at the European University Institute in Italy. She holds a PhD and a Masters in Political Sciences from Sciences-Po (France) and is on a comparative journey between Malaysia and Tunisia where she continues to do fieldwork. She is the editor of Misplaced Democracy: Malaysian Politics and People.

—

[1] British Journal of Psychiatry (1994) 165, 685-689

[2] Observations and interviews with Silat practionners and claiming membership to affiliated Pekida groups. Numerous Pekida members are recruited in silat associations. Video of rituals may be seen on youtube.

[3] Clarification of the incident by Malaysia’s Inspector General of Police http://www.kinitv.com/video/20678O8

[4] See Greg Lopez, “We are not Racists!” At http://www.newmandala.org/2011/11/30/were-not-racists/

[5] See Dr Ranjit Singh Malhi Open Letter in The Star at http://www.thestar.com.my/Opinion/Letters/2015/03/13/Glaring-bias-in-history-book/, the CPI article series on the NGO and Scholars initiative of Reclaiming Malaysian History at http://blog.limkitsiang.com/2011/05/19/reclaiming-our-truly-malaysian-history/

[6] The youth in question was unemployed and had disabled parents. http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/youth-at-centre-of-low-yat-brawl-charged-with-theft-claims-trial

[7] Roger Petersen and Sarah Zukerman, Anger, Violence and Political Science in M.Potegal, G. Stemmler, C. Spielberg (eds.), International Book of Anger: Constituent and Concomitant Biological, Psychological, and Social Processes, Spinger 2010, 561-583.

[8] See http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2011/12/16/najib’s-split-personality/

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss