On 17 August 2024, Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, travelled to the still-under-construction new capital, Nusantara, to celebrate Independence Day. The presence of both the president and his successor, Prabowo Subianto, however, has not been enough to quell the ongoing controversies and discontent. Five years after Jokowi’s announcement of the Nusantara Capital City (Ibu Kota Nusantara, or IKN) project, widespread scepticism has emerged, often from drastically opposing perspectives.

Some question whether Jakarta-based public servants will be willing to relocate to Nusantara’s location in East Kalimantan, a region perceived as backward and isolated. Others express concern for the land and the local residents who are soon to be displaced. The president had once proudly announced his intention to personally move from Jakarta to the new presidential palace by the time of Independence Day this year. Three days before the date, he declared that the plan would be postponed due to incomplete infrastructure. This leaves critics in a difficult position: should they rejoice over the project’s slow progress, or worry about the prolonged uncertainty over its prospects?

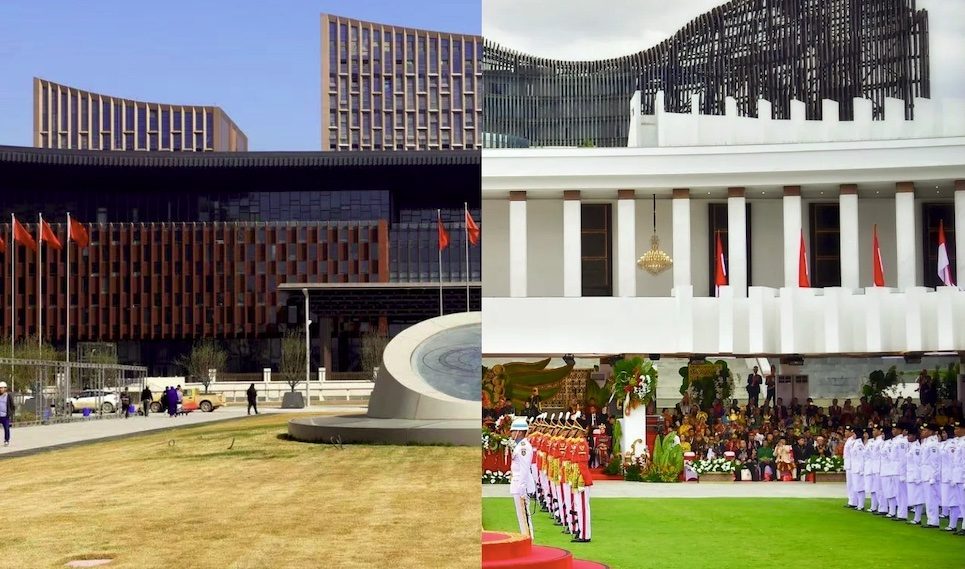

Standing in front of the unfinished presidential palace, the Istana Garuda, Widodo would be picturing a finished building that looks surprisingly comparable to something like in the image below, which shows the business service centre of China’s Xiong’an New Area, a planned city in the hinterland of Beijing that has been dubbed Xi Jinping’s “pet project”. Surprisingly, few have discussed the ideological and practical similarities between these two projects. Indeed, Indonesia has its own history of planning to relocate its capital from Jakarta that is almost as long as the history of the republic itself. When international comparisons are given, the examples are usually Canberra and Brasilia (Putrajaya and Naypyidaw come next). Xiong’an, situated in north China, is rarely talked about—perhaps precisely because Xiong’an’s own controversies are too similar to those of the IKN.

Business and Service Convention Center, Xiong’an (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Dubbed a “millennium plan”, Xiong’an New Area is the crown jewel of Xi Jinping’s era of mega-projects. It aims to gradually shift much of Beijing’s population and activities to a previously desolate area 180 kilometres to its south, in order to alleviate the capital’s perceived worsening overpopulation. With billions of Chinese yuan invested in its preliminary construction, the project emphasises sustainability and quality rather than the rapid pace of development that characterised China’s previous four decades of urbanisation. By “millennium”, Xi’s administration shows its determination to bring about permanent changes to the nation that are beyond the limits of presidential terms—or in the Chinese historical consciousness, dynastic rotations.

Many legitimately speculate that pushing through this costly project was a major motivation behind Xi’s pursuit of a third term—a scenario not unfamiliar to Indonesians after witnessing Jokowi’s political manoeuvring in the recent election. After years of intensive construction, local villages have been razed, new buildings have sprung up, but few newcomers have moved in. Xiong’an’s experience over the past decade shows us both the best and worst-case scenarios Jokowi could imagine: speedy, high-quality construction, but with lacklustre economic returns.

Xi Jinping visits the Xiong’an New Area, January 2019. (Photo: Xiong’an New Area on Facebook)

Deindustrialisation

A common pitfall for both defenders and sceptics of the infant IKN was to wishfully imagine a place of purity—of pristine nature and undisturbed natives. Similarly, observations on the Chinese equivalent often emphasise the tabula rasa state of the Baiyangdian wetland chosen for Xiong’an’s development. The media tend to be preoccupied with events within the specific administrative boundaries of Penajam Paser Utara district, the site of IKN, and Xiong’an, which are indeed rural. Once we zoom out to the larger economic structures of East Kalimantan and eastern Hebei province, the pictures will look very different.

In East Kalimantan, mining, oil and gas refining, and timber processing have been traditionally the dominating economic sectors. The society of East Kalimantan came under as much, if not more, influence of exploitative industrialisation, demographic displacement, and settlement from outsiders than any the other major island of Southeast Asia. Coal mines and oil wells had begun invading the Balikpapan area for more than 130 years, bringing in large numbers of labourers from Java and China. Even before these industrial developments, the towns of Samarinda and Paser were urbanised by generations of migrants from the south coast of Borneo as well as Sulawesi.

The psychological shock, or “kaget”, of building modern industrial cities amidst the jungle is already relegated to the past tense. Expecting environment-oriented criticism of IKN, the Indonesian government had been gradually shifting its narratives about the new capital from that of “building a green city in the primary forest” to that of “reclaiming a green city from misused and depleted wastelands.” The effort could be seen in the gestural closing of several illegal mining concessions on land reserved for IKN. Observers doubt the substance of this move, as many mines and drills, including those owned by the very individuals pushing for the project, continue to operate unhindered.

The experience of Hebei, the province where Xiong’an is located, in the past decades offer some lessons for the potential future of East Kalimantan. Once a predominantly agricultural region, the province rapidly industrialised in the 20th century thanks to the discovery of mineral reserves. As nearby Tianjin and Beijing shifted towards service and technological sectors, Hebei received most of the heavy industries moving out from these large cities in the 1990s and early 2000s, worsening the already severe pollution of its environment. Degradation of the land’s arability made the populace even more dependent on the industrial jobs in a vicious cycle. Even though it is located right next to the capital, Hebei has ironically long been considered a peripheral “backwater” amidst China’s extremely uneven economic development.

Xiong’an New Area photographed from a drone, March 2024 (Photo: Xinhua)

After Xi assumed power in 2012, he had been determined to curtail the worsening air pollution in Beijing and to return “clear water and green mountains” to China’s heavily industrialised north, pushing for Hebei’s deindustrialisation. A large number of cottage industries were shut down every year since then, and air quality in Beijing had been largely restored. Baoding, the prefecture-level city (equivalent to an Indonesian district or kabupaten) where Xiong’an is located, proudly broadcasts itself in 2018 as the first one of the province achieving “steel-free” status, meaning that every steel mill has closed down.

In this sense, IKN and Xiong’an are ideologically motivated projects imposed by political elites in the centre to transform a periphery perceived as backward, dirty, and inefficient. The catch lies in the obvious economic dependence of both China and Indonesia on the very sectors they ostensibly seek to eliminate. Local governments in Hebei struggle financially without the tax revenues from smaller industries, not to mention the livelihoods lost by ordinary citizens. Fearing a similar outcome, Jokowi and Prabowo Subianto have yet to commit to removing dirty industries from East Kalimantan. IKN’s initiative to install solar panels pales in comparison to the province’s colossal coal-producing capacity, which sustains hundreds of thousands of families. Jokowi has also repeatedly promised to build, expand, or retain oil and gas facilities in East Kalimantan, likely to maintain morale in one of the few regions of Indonesia where hilirisasi, or industrial down-streaming, has yielded tangible economic benefits.

Deglobalisation

At first glance, the two projects receive markedly different treatment in their respective countries. While Xi’s team showers Xiong’an with grandiose terms such as “millennium plan” and “ecological civilisation” in official rhetoric, it is not an attempt to create a new political centre from scratch. Critics have noted certain political symbolism in Xi’s vision for Xiong’an, but these pale in comparison to the heaps of nationalistic narratives surrounding IKN. In this year’s Independence Day celebrations, the participating grandees dressed colourfully in traditional ethnic fashions (pakaian adat) from across the archipelago. A real-life version of Tien Soeharto’s nationalistic playground, Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, was broadcasted in front of the whole country, matching the actual installation of a miniature IKN in Taman Mini itself in 2023. Xiong’an has had its moments like this, but after seven years it has largely faded from the Chinese public attention.

If we look beneath the surface of nationalism, however, IKN and Xiong’an projects share another layer of shared ideology. By deemphasising metropolises such as Beijing and Jakarta, IKN and Xiong’an represent the two governments’ disengagement from global capitalism as source of legitimacy. Asia’s political elites are seeking new paradigms in a deglobalising world, and this introspective turn is a part of it. As seen in the landmark structures of IKN and Xiong’an, there is a clear effort to create aesthetically distinctive images and icons that diverge from the typical modern Asian city. Yet, an uncanny similarity emerges: an architectural style reminiscent of Stalin-era Soviet bloc and the imperial Japanese Teikan Yoshiki of Manchukuo. Both were attempts to deliver nationalistic bearings for architectural aesthetics in an industrialising and globalising world, comparable to those promised by IKN and Xiong’an. At their core is the symbolic purification of the self from Western pollution. The pool of alternative artistic inspiration, however, appears limited.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo delivering a presentation on the then-unnamed new capital city, October 2022 (Photo: Joko Widodo on Facebook)

In the case of IKN, various Indonesian officials have already emphasised its aesthetic mission to represent an Indonesia free of Dutch colonial influences . The Indonesian government does not shy from admitting Jakarta’s myriad problems, but seems to blame many of them on the colonial origins of the city. Ridwan Kamil, a potential contender for the governorship of Jakarta who also holds the office of IKN’s “curator”, repeatedly made promises about purging IKN from colonial “concepts” and “nuances” of Jakarta. Such was also the reason why cities with deep colonial histories, such as Bandung and Bogor, were dropped as candidates. Balikpapan’s colonial origins, meanwhile, could be conveniently ignored, as IKN comfortably sits outside its administrative boundaries. Superficial as it sounds, Jokowi is indeed bringing into reality an ideological ambition that had been dreamt of by generations of Indonesia’s nationalists. By way of the trans-Kalimantan highway, one can reach IKN from Palangkaraya, Soekarno’s own attempt to create a purely Indonesian city unpolluted by colonialism.

The growing contradictions of Singapore’s HDB scheme

A notionally egalitarian public housing program has come to fuel class and intergenerational inequalities

Both projects thus encompass some degree of deterrence or resistance against the West-dominated world order. Unfortunately, to a large degree, the common people who actually live in these countries still have to abide by the rules of global capitalism. Jakarta and Beijing will continue to attract migrants from the provinces, while Nusantara and Xiong’an’s current desolation might persist for a while. Slow return of investment is far from the worst case scenario, though: thanks to the late James C. Scott we know how bad and costly it can get if governments indeed turn to draconian measures to force particular demographic patterns or to force mostly any grand designs. With Beijing’s violent eviction of migrant workers from its suburbs in 2017 still looming in the residents’ memory, would the two governments actually wait for a thousand years?

A future for the locals?

By 2024, the Xiong’an New Area has moved most of its original villagers into newly completed apartment buildings. A video on Bilibili shows us an honest conversation between the content creator and a villager-turned-taxidriver in Xiong’an. As expected, being uprooted from one’s community and dropped into cell-like units makes a shocking experience. Driving through empty streets, the middle-aged man complained about a few things. Costs for utilities and groceries used to be negligible in a rural economy, but suddenly has to be dealt with. Isolation in gated communities makes life tedious and boring. He is still hopeful about the future. He feels that it will be worth it as long as his children and grandchildren may one day benefit by way of having access to good education in a country with extremely unevenly distributed education resources.

Such is one of the few lessons IKN might learn from Xi’s gamble. While East Kalimantan boasts cities with some of the best quality of life throughout Indonesia, its rural population rarely reap the benefits— especially in terms of access to education. Indigenous and rural communities in Penajam Paser Utara have already made an explicit petition that some of the educational resources that might show up as the Indonesian capital moves should be reserved for them. Amidst all the grand narratives of nation, colonialism, and environment, education remains perhaps the only substantial asset that urbanisation could potentially hope to bring to the displaced locals. As IKN moves forward at a speed that starts to far outpace Xiong’an, we cannot be sure of anything just yet.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss