Prologue & Introduction

What is the nature of the Philippines? What is it that lies at the core? How does it tick? What is the one piece of art, object or artefact that could tell us this?

These questions were haunting the periphery of my thoughts during a hot, late-December day spent in the exhibition ‘Passion + Procession: Art of the Philippines’, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW). I wanted to use the objects in the exhibition to uncover some inner truth, the essence of the Philippines so that I could write a simple article for you explaining the history and culture of the whole of the Philippines. By the end of this article I will tell you what I found while hunting for the ‘secrets’ of the Philippines, but first I need to tell you about the gallery – and about myself.

AGNSW is extremely important to me. I grew up outside of Sydney – a terribly serious, thoughtful but creative teenager who devoured books and ideas from other places and times. AGNSW was a haven of beautiful things and exciting ideas to escape into. It was free, open, welcoming, and it wanted you to be there.

In the late summer holidays, having exhausted the local shopping centre and beach, my friends and I would wait on a seedy, hot concrete station platform for the slow creep of a 50 year-old train to Sydney. The city could not have been more of a contrast to home. Leaving the city station you could walk through the calm green trees of the Domain until, greeted by a cool harbour breeze, you reached AGNSW’s inspiring, grand classical building of warm honey sandstone founded in 1874, the same year the French Empire took control of Vietnam.

Approaching the Art Gallery of NSW from the Domain (https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/visit-us/)

We would spend half a day in the gallery, then move to the adjoining Botanical Gardens – all the while avoiding the nearby Australian Museum with its prohibitive antisocial entry fee. In the early evening we would trudge up the rolling grassy hill back to the station, boarding the decrepit train and returning home, a minor regional centre with pretentions-to-city status, whose skyline was dominated by shadowy looming hulks of empty multi-story carparks.

So when my friends in PoP told me about the Passion + Procession exhibition, I suggested we should go together. For me, AGNSW has always been a natural place for mixing friendship and ideas.

Like the summers of memory, it was one of those steaming hot days when the sweat rolls off you and the pavement sizzles. I strode from the city’s Christmas shopping bustle, through the Domain, between the shade of sandstone columns and into the gallery, crossing the familiar cold mosaiced floor.

Entrance vestibule of the AGNSW (https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/venues/vestibule/)

The Exhibition Passion and Procession: the Art of the Philippines

The exhibition was tucked into a back fold of the gallery’s main floor, in a space used for various temporary exhibitions of Asian art, previously exhibiting Buddhas from across Asia, and ancient Afghani gold. Now, a lone headless and limbless Buddha resides at the periphery of the Philippines exhibition, arrested in place by a pair of metal poles, furtively haunting the entrance to the Catholic-dominated Philippines exhibition.

Standing Buddha 518-618 CE, AGNSW (https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/432.1997/)

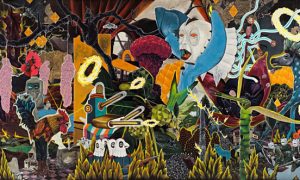

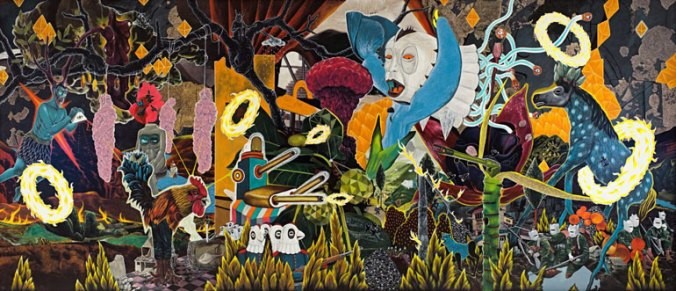

I went into the exhibition, wanting to find ‘the object’: the artefact that would let me write about the whole of the Philippines, an art-work that would illuminate a nation. The first work, Do you have a rooster, Pedro? by Rodel Tapaya, was really fun, and seemed like a good contender. We were dwarfed by a giant riot of colour, like a puzzle. I drew on half-remembered Filipino mythology discussed by my partner’s family. Here a manananggal (vampire) or aswang (witch vampire), there a Diwata (forest/mountain spirit) or Kapre (tree spirit). These figures were all woven between a complex telling of Filipino history showing traditional Filipino culture as central actors in the story of the Philippines. I was sifting the art, solving clues as one might a crossword puzzle. I was disappointed that the creatures were not identified in the description next to it, and whilst the descriptive labels talked of folklore, I knew that for many in the Philippines today, these were not passive historical bogeymen, but real beings that played a part in people’s everyday lives. And still, the cryptic question that I could not unpick haunted me: was what was the essence of the Philippines, what was behind the art?

Rodel Tapaya, Do you have a rooster, Pedro? (Adda Manok Mo, Pedro?), 2015-16. AGNSW.

We shifted jerkily, and via the wrong path, through the art, and as I scrutinised each new object, canvas and label I asked myself with increasingly conscious frustration, ‘can this be the artwork that could be a microcosm for the Philippines? Could this be the work that gives me something insightful to say?

Nona Gracia, Recovery, 2017 (Photo by PoP)

There was one artwork that came very close to doing this, Nona Gracia’s Recovery. Recovery is a collection of 60 light boxes with X-ray film. Each light box displayed an X-ray of different objects that belonged to the Ifugao highlanders, a prominent ethnic minority in Central Luzon. The Ifugao are historically known for their incredibly successful violent and strategic resistance to the Spanish invasion and colonisation by the Catholic church. Today the Ifugao are increasingly recognised for creating one of the historical wonders of the Philippines, a giant complex system of spectacular rice terraces, snaking many kilometres through mountain valleys. These are thought to have enabled the Ifugao to hold out against the Spanish invasion taking place in the coastal lowlands; they are also now featured on a Filipino bank note.

Not only did this community resist European colonialism, in its military, economic and religious forms, they re-engineered their entire landscape, remaking mountains and shifting streams and rivers. Today this incredible landscape is internationally recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage site. And there is currently an important research project working on understanding the landscapes complex history.

Closer View of the Banaue Terraces, Agricmarkting (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki.Banaue_Rice_Terraces#/media/File:Banaue_Rice_Terrace_Close_Up_(2).JPG)

View of the town of Banaue from the Ifugao rice terraces, CEPhoto Aranas (http://en.wiki/Banaue_Rice_Terraces#/media/File:Banaue_Philippines_View-of-the-Town-01.jpg)

The artist, Nona Garcia, was raised in a hospital that her parents ran, in the capital Manila – which gives us some social insight into who is and is not able to become an international artist. Nona Garcia now lives in Baguio, a city to the north of Manila located on the edge of a cultural division between the historically colonised lowlands of the Illocos and the Ifugao highlands. Garcia is fascinated by medical imagery and ‘exploring hidden meanings’. Whilst I am grappling in my search for the spirit of the Philippines, Garcia seems confident in having found the spirit of the Ifugao.

For her there are a few entangled things going on in the artwork. First, a tension between ‘old-traditional’ ways of life and healing, vs. ‘modern-scientific-rational’ ways of life. The traditional and modern healing tools are brought together in a strikingly clashing contrast. Ifugao religion/traditional knowledge is literally illuminated and brought into focus by the modern technology – and thus revealed as passive folk-lore.

It is interesting, and perhaps illuminating of the Philippines itself, that this critical juxtaposing of modern X-rays and traditional highland healing objects, the new scientific, and the seemingly old and superstitious, is only applied to the traditional beliefs of an ethnic minority, and not applied to Catholicism which predominates throughout much of the Philippines. This theme of comparing ‘oldy-worldy-folk ways’ (non-Catholic) religion with modernity came up in many parts of the exhibition. Last week’s review talks about this as well, especially in relation to the Islamic South, and also central Philippines. The description of the artwork concludes by claiming that the art brings us closer to ‘lost knowledge’, suggesting the Ifugao living community as a portal into the past, whilst the electrical buzz of the lights, according to the image description, symbolises that the Ifugao are one with the crickets of the forests and mountains (seemingly despite the giant world heritage listed rice terraces revealing that the Ifugao remade the natural world around their own needs). Though I disagree with Gracia’s interpretation of the Ifugao, Gracia’s artwork is thought-provoking, and the use of X-ray and traditional healing objects communicates her ideas clearly and in a visually enchanting way.

The Bigger Picture

If we were to travel to Baguio, the city in which Garcia now lives, we would find that simplistic two-dimensional representations of the Ifugao abound in public art and advertisements. For example, the ‘Igorot Steps’ (Igorot is a somewhat derogatory term in the majority language Filipino/Tagalog to refer to highland communities, regardless of how these communities identify themselves) are known to depict Ifugao people through stereotypical tropes such as dark-skin, weapons, wild hair, head-hunting and superhuman physical strength.

Igorot Stairs in Baguio (http://mapio.net/pic/p-11991515/). Note the roosters perched on the stairs.

Igorot Stairs in Baguio City (http://kulang-sa-tulog.blogspot.com.au/2008/03/igorot-stairs-in-baguio-city.html)

My feeling is that it is important to have ethnic minorities represented in exhibitions seeking to stage the whole nation. However where things become tricky is whether the minority is represented by the majority, or if that community’s own voices are present?

Both Garcia’s thoughtful, beautiful artwork, and these problematic statues, purport to have found the essence of the (still thriving) Ifugao. For Garcia it is about lost traditional knowledge, and being one with the natural world, in shocking contrast to modernity and science –and in denial of historical and anthropological research. For the public statues in Baguio, the depiction is more brutal, the essence here is one of visceral, violent primitivism. Although the intentions and context are very different, the meaning, the implication, is connected: that the Ifugao are simple and belong to a vicious and visceral ancient past. In contrast to the relatively more human looking Manila elites, Presidents and Cardinals, depicted at the top of the stairs looking down upon the Ifugao.

President Aquino and Cardinal Sin (https://littledrifteronearth.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/dsc_1191.jpg)

President Arroyo stands in front of an Igorot warrior ready to throw a spear (https://littledrifteronearth.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/dsc_1209.jpg)

It took me a long time to get to grips with my own thinking about the exhibition. It was not until, weeks later, I was with my friends, in an exhibition of old Dutch art, staring at a painting of Dutch- Batavia (Jakarta), and ships anchored in a colonial perspective, when I realised where I had been going wrong. I would never visit an exhibition of Western art trying to uncover the ‘spirit’ of Dutch, British or Australian-ness (though Weber might). The idea that one artwork could be a window into the entirety of a nation, encompassing the nuances of many diverse communities, is obviously ridiculous. I would at best laugh and at worst be outraged if someone tried do use this method to any community of people that I felt part of.

Aelbert Cuyp ‘A senior merchant of the Dutch East India Company and his wife; in the background the fleet in the roads of Batavia’ 1640-60. (http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/booksandarts/aelbert-cuyp/9136912)

As a recently highly controversial public intellectual sates, perhaps how we look at the ‘window’, the source we are interrogating, reveals a lot more about ourselves and the source itself, than what we are seemingly able to ‘understand’ by peering through it to see a clearer picture of the past.

Ergo, how can we tell a simple story of the Philippines? What is the nature of the Philippines? What is it that lies at the core, its essence, its most secret soul?

Perhaps some better questions would be:

Why do we not seek out complex understandings of what we are studying? Why presume that there is an essence to the Philippines? Why do we search for some inherent defining characteristic or trait? And walk into an exhibition of Dutch, Australian or British art and scoff at asking these kind of questions, when they are habitual when viewing the art of others?

The Punchline

In my own way, despite all my intellectual post-colonial training, and progressive aims, by seeking out an object to tell a simple story of the Philippines, I was effectively attempting to do on a larger conceptual scale, what had made me feel uncomfortable about Garcia’s work, and horrified by the public ‘monuments’ on the Igorot Stairs.

In different, but nonetheless similarly violent ways, each has taken complex, diverse, historically nuanced peoples, maimed them, shrunk them and in doing so reduced these rich dynamic cultures into simplistic caricatures. This approach does not build understanding, or inform, it packages, destroys and finishes the conversation.

Conclusion & Epilogue

Free public art galleries and museums are vital places for challenging, changing and distilling our big ideas. I went into the Philippines exhibition, and like my much younger self, I was excited and seeking to learn. Though this time I tried to use art to find an object that I could use as a window to tell a simple story of the Philippines: how did it work, what it made it tick?

A big problem with communicating academic information to a public audience is that we often resort to simplification and generalisation (to an extent, art suffers from a similar problem). This occurs when we try to tell a big story in a short time-frame. We often end up constructing flat, simple pictures that lack dynamism, nuance and complexity, at times resorting to crude clichés to get our point across. It may be that academics and researchers should strive to not simplify, but inform popular discussion and ideas in a nonetheless accessible way. It may be that as academics we should be exploding, exploring and complicating simple explanations and narratives of how the world works (but not obfuscating with unnecessary jargon). The end result, and this is something I have tried to do in this article, is to communicate my understanding of the complexity of one small part of the world, to explain some of the difficulty with simple explanations and encourage others (and myself) to think in more nuanced way. Finding things complicated is not entirely a bad thing. By explaining that the world presented in a news story, in a presidential candidate’s election speech, in the unquestioned words of a preacher or in a statue cannot be as simple it purports to be, we are making a small but important contribution.

Over the course of the weeks since visiting the Passion + Procession exhibition, I have incrementally come to re-appreciate that the answers we seek are illustrative of the questions we ask. The questions we ask reveal the limits of our imagination, and the assumptions that constrain us. The review of the Passion + Procession exhibition has become a ‘review’ of myself. My conclusion – I still have much to learn!

The Author wishes to thank friends, family and colleagues who provided advice on this article.

We will soon reveal the author of each article. Please comment below, or continue the conversation on the Perspectives on the Past’s online community

AGNSW (https://www.facebook.com/pg/ArtGalleryofNSW/posts/?ref=page_internal)

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss