20 years ago, political scientist Chai-Anan Samudavanija coined the esoteric term “Pracharat” to refer to civil society in the Thai context, where the transformative potential of civil society depends on patronage by or cooperation with the state. The term became widely known only recently, after it was adopted by Thailand’s most recent junta, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), as well as its successor government under the military’s proxy party, Phalang Pracharat.

Shortly after the NCPO came into power, the regime began employing the term to articulate a development ideology revolving around co-operation between the state, the private sector and civil society. It distinguished this approach from the “populist approach” of previous governments associated with former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, alleging that these administrations had irresponsibly prioritised policies that would be popular among the electorate in order to secure short-term political outcomes.

In reality, the policies that the NCPO branded under the Pracharat umbrella were initially not so different from those that previous governments had implemented. Consider the first generation of Pracharat policies. Pracharat funds (kong-thun pracharat) was essentially a modified version of the already existing village funds. Pracharat credits (sin-chua pracharat) could be compared to already existing support schemes for SMEs. Government-certified Thong-fah Pracharat shops selling subsidised goods harked back to Thong-fah shops.

But Pracharat policies have clearly evolved in a distinct direction in the years that have followed. That evolution illuminates well the conditions that have shaped the policies of the NCPO, especially its welfare policies which are the primary focus of this article.

The development of welfare policies according to the Pracharat approach—which this article calls Pracharat welfare—reflects certain changes taking place in Thai society, particularly to the relationship between the state and rural citizens. It is widely acknowledged that this relationship, which is at the heart of Thai politics, underwent a period of change during the Thaksin era, during which the rural poor were widely described by scholars as experiencing a “political awakening.”

The state–rural relationship underwent another period of change when the NCPO came into power, but this significant evolution has hardly ever been the focus of analysis. This article begins by tracing the development of Pracharat welfare, describing its origins and defining characteristics. From there, we offer some preliminary analysis on how Pracharat welfare is stimulating ongoing changes in the relationship between the state and rural areas. We briefly analyze how these changes affect the lives of rural citizens.

The evolution of welfare in Thailand

Prior to the genesis of Pracharat welfare, welfare policy in Thailand was in the midst of flux, reflecting fundamental changes in how rural citizens related to the state. The first time a Thai government showed interest in welfare policies may have come after the transition from absolute monarchy in 1932. The “National Economic Policy” of Pridi Banomyong involved efforts to establish a system for the state to play a role in alleviating the poverty of farmers in rural regions, regarded as the most impoverished demographic in Thailand.

But the onset of World War II followed by politics under the conditions of the Cold War created new government visions of welfare. Welfare under the dictatorship of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat took a minimal form, reflecting the state’s efforts to exploit farmers and the agricultural sector by channeling surplus value into supporting the growth of private business and urban industries.

Minimalist welfare based upon an extractive relationship between the state and rural citizens began to change when the military regime was faced with the challenge of social movements in the 1970s, and even more so when Thailand began to democratize in the 1990s. Governments began to install more expansive welfare programs, with the state clearly taking on the role of supporting rural livelihoods. These changes crystallised most clearly when Thaksin Shinawatra came into power with a suite of policies aimed at assisting agriculturalists, including subsidies for agricultural goods and relief from debt. Rural populations also benefitted tangibly from broader welfare policies such as village development funds and universal healthcare.

Welfare policies became the centre of Thaksin’s political successes. Successor parties connected to him including the People’s Power Party and Pheu Thai ran on similar platforms. But such policies came hand in hand with the buildup of opposition from a multitude of groups which coalesced to bring down the governments of Thaksin and Yingluck Shinawatra, in part by branding the welfare policies pejoratively as “populist”. Most visible in the form of the large-scale yellow-shirt protests which pre-empted the coup of 2006, the opposition to Thaksin’s welfare policies would be one key factor that eventually contributed to the emergence and development of Pracharat welfare.

Critiques that Thaksin and Yingluck spent wastefully forced the NCPO to distinguish its welfare policies from that of previous governments. Initially, the NCPO began by de-emphasising the importance of pro-agricultural policies and put an end to a number of state initiatives aimed at citizens with low-incomes. For example, on 1 November 2017, a policy allowing for free bus and train rides was annulled. The rolling back of welfare was combined with regular criticisms by junta leaders that universal healthcare is a wasteful use of state resources. One such speech by junta leader General Prayuth Chan-ocha once reasoned: “There isn’t enough in the budget for public health … How on earth can we have universal healthcare? Is that even possible? … That’s a populist policy. But it’s been made into law. The people are already reaping [the benefits]. There’s nothing I can do. But we are ready? On average, [the policy spends] 2,900 baht per citizen … Is that enough to keep everyone in good health? Will the hospitals be able to keep up? Curing every disease … the hospitals will go bankrupt!”

Pracharat welfare

The “welfare card” initiative championed by Phalang Pracharat, commonly called “the poor’s card” (but kon-jon), has been a key element of Pracharat welfare. The policy provides income support to those who have been qualified by the government as poor, giving them 200-300 baht per month for the purchase of consumer products from Thong-fah Pracharat shops. The holders of the cards also receive allowances for public transportation fees and cooking gas. Additional income support is given to holders who qualify as disabled, elderly and to those who join a job-training program.

The welfare card policy embodies the three key characteristics of Pracharat welfare.

First, Pracharat welfare is poverty-targeting welfare: the welfare card is the first nation-wide welfare initiative in Thailand that exclusively targets the poorest through a means-tested method. Those eligible for the card must register with proof that their income is no more than 100,000 baht per year, as well as pass an inspection into whether they possess financial assets worth more than 100,000 baht or land larger than 10 rai. A welfare initiative targeting the poorest is in alignment with the NCPO’s 20-year strategic plan, which specifies that the development of welfare should aim to support the opportunities of the lowest-earning 40% of the population. The orientation of welfare exclusively at the poorest is also clearly a response to demands that welfare policy make efficient use of state funds.

Second, Pracharat welfare is connected to the aim of stimulating grassroots economies. Thailand’s economic growth has continually slowed since the NCPO came into power, especially when it comes to the agricultural sector which faces the problem of declining prices for goods. Negative economic growth from 2014–16 affects the income of rural citizens. As of August 2019, 14.6 million people are registered for welfare cards. Pracharat welfare aims to stimulate the economy by boosting the purchasing power of low-income citizens, especially in rural areas. Besides the regular stipend to which holders of the state welfare card are entitled, the card is the medium for several other measures aimed at promoting cash flows. For example, the government is currently considering a proposal where card holders would be entitled to 1,500 baht to spend on domestic tourism.

Third, Pracharat welfare reflects the deepening role in welfare of an increasingly intimate relationship between the state and large corporations/conglomerates. Since the launch of the Pracharat initiative, co-operation between the NCPO and Thailand’s largest corporations/conglomerates has been clearly visible. 73% of the committee appointed by the NCPO to steer the various development projects under the Pracharat umbrella are representatives from the private sector, coming from major conglomerates such as Charoen Pokphand, True, Mitrphol, PTT and Siam Cement.

At first, the welfare card could only be used to purchase goods at certain chain stores, which led to criticisms that the policy had been designed to benefit the large conglomerates participating in the Pracharat initiative. Though those limitations have since been loosened, it remains important to note this broader context in which major corporations/conglomerates are playing an increasingly pervasive role in the implementation of welfare policy.

The legacy of Pracharat welfare

In his important work Thailand’s Political Peasants, Andrew Walker spoke of changes in the relationship between the state and rural citizens during the Thaksin era. He characterised the changes as taking place under two conditions. First, the state had taken up the duty of supporting rural livelihoods. Second, rural citizens had experienced economic development such that many had achieved middle-income status.

Walker invoked the concept of a “political society” to characterise rural Thailand under that changing relationship. He proposed that the fundamental political desire of rural citizens was to have a participatory relationship with the state with the opportunity to secure resources and power in ways that would benefit them. The participation of rural citizens in governance manifested in several ways during the Thaksin era, from the prominence with which their interests were represented in policy to development projects where state representatives collaborated with various rural groups. The new political desires of rural citizens were simultaneously the basis of new political identities.

But for middle-class, urban detractors of Thaksin’s welfare projects, his policies were insufficiently regulated and so were thwarted by corrupt and private interests in rural communities. Such criticisms were reflected in their criticisms that Thaksin’s welfare policies amounted to no more than populism.

How has Pracharat welfare altered the once participatory relationship between rural citizens and the state? If the trajectory of Pracharat welfare continues, and the three characteristics described above intensify, it will not be an exaggeration to propose that rural society is currently moving out of the hands of “political peasants”.

It’s true that the Thai state continues to support rural livelihoods, though not as extensively as in the past. But Pracharat welfare constructs a relationship between the state and rural citizens whereby the latter do not participate in politics in order to secure benefits. Instead, state officials and bureaucrats use their power and expertise to intervene and distribute aid to the poorest. In place of political participation is a technical screening process and the distribution of benefits only to those who are eligible. It could be said that Pracharat welfare is eroding the value and importance of the “peasant” identity in politics, while simultaneously replacing this with the identity of “the poor.”

How does the erosion of political participation tangibly affect livelihoods in rural regions? We suggest approaching this question from two preliminary angles: (1) changes in the agricultural sector and (2) reductions in rural inequality.

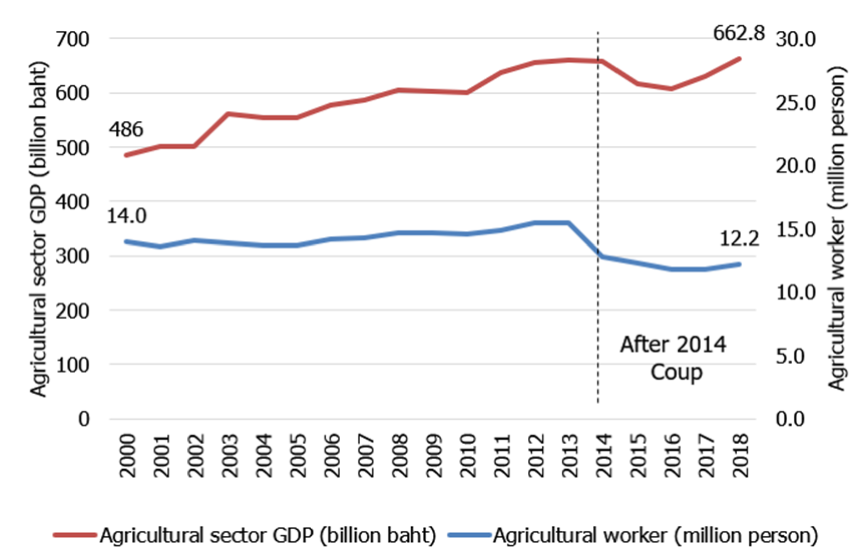

According to Walker, one outcome of the peasant society was that the state actively worked to maintain rural society. The agricultural sector throughout the Thaksin and Yingluck era (2000–14) hardly contracted, both when it comes to production output and the number of workers employed.

Figure 1: Agricultural sector GDP and the number of workers

The legacy of the NCPO and Pracharat welfare has perhaps been the reversal of this trend in preserving the agricultural sector. The sector may once again return to shrinking. The economy is sluggish in rural areas, the prices of agricultural goods are low, and support from the state is falling. Surviving in the agricultural sector these days is becoming increasingly difficult.

While most rural people have largely risen above impoverishment, Thailand remains marked by extreme inequality. Pracharat welfare was arguably designed within a development paradigm which expects that poverty-oriented aid will efficiently redistribute resources to improve the status of the poor. But the other key characteristics of Pracharat welfare may make it difficult for this to be actualized.

Pracharat welfare was propelled by the movement opposed to populism. Given that the attitudes to welfare policy of a large section of Thais remain negative, these same conditions are likely to constrain the expansion of welfare under the Pracharat approach. It will be difficult for even the provision of welfare only to the poorest to avoid these negative attitudes, which may grow aggressive if the state makes moves to expand entitlements under Pracharat welfare. The objectives of Pracharat welfare also remain linked to the efficient use of state expenditure and stimulating the economy. These competing aims muddy the goal of reducing inequality and easily leaves it open to distortion under the guise of meeting the other objectives.

Finally, increasing intimacy between an undemocratic state and major conglomerates is the defining relationship driving welfare policy. It is difficult to expect that such an environment will encourage the reduction of income inequality in Thailand.

จากคำที่คนไม่ค่อยรู้จัก ที่ชัยอนันต์ สมุทวณิชประดิษฐ์ขึ้นเมื่อยี่สิบกว่าปีก่อน เพื่อให้หมายความถึง “ประชาสังคม” ในบริบทแบบไทยที่ยังต้องคอยอาศัยความร่วมมือจากรัฐ คำว่า “ประชารัฐ” ได้กลายมาเป็นคำที่ถูกใช้อย่างแพร่หลายในช่วงหลายปีที่มาในยุคของคสช.และพรรคพลังประชารัฐ

เมื่อถูกใช้เป็นครั้งแรกหลังจากการเข้าสู่อำนาจไม่นานของคสช. “ประชารัฐ” ถูกระบุให้หมายถึงแนวทางที่เน้นการร่วมมือประสานกันระหว่างภาครัฐ เอกชน และประชาสังคม โดยคสช.กล่าวอ้างว่าเป็นแนวทางที่แตกต่างไปจาก “ประชานิยม” ที่รัฐเน้นทำเรื่องที่ประชาชนให้ความนิยมเพื่อหวังผลทางการเมืองในระยะสั้น

ความเป็นจริงแล้ว ในช่วงแรกเริ่มนโยบายที่ถูกโยงเข้ามาเป็นนโยบายประชารัฐก็ยังไม่ได้แตกต่างไปมากจากนโยบายที่จัดทำอยู่แต่เดิมโดยรัฐบาลก่อนหน้าคสช. ไม่ว่าจะเป็นกองทุนประชารัฐซึ่งแปลงสภาพมาจากกองทุนหมู่บ้าน โครงการสินเชื่อประชารัฐซึ่งมาจากโครงการลดภาษีผู้ประกอบการขนาดกลางและเล็ก และโครงการธงฟ้าประชารัฐซึ่งมีที่มาจากร้านธงฟ้า อย่างไรก็ดี ในช่วงหลายปีถัดมา นโยบายประชารัฐก็มีทิศทางที่แสดงความแตกต่างอย่างชัดเจนขึ้น สะท้อนถึงสภาพต่างๆที่โยงกับการกำหนดนโยบายของคสช.ได้เป็นอย่างดี โดยเฉพาะนโยบายในด้านสวัสดิการ ซึ่งจะเป็นชุดนโยบายที่บทความชิ้นนี้ให้ความสนใจเป็นหลัก

กำเนิดและพัฒนาการของนโยบายสวัสดิการบนแนวทางประชารัฐ ซึ่งบทความชิ้นนี้จะขอเรียกว่า “สวัสดิการประชารัฐ” ช่วยสะท้อนการเปลี่ยนแปลงสำคัญในสังคมไทย โดยเฉพาะในความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างรัฐและชนบท ความสัมพันธ์ที่เป็นหัวใจหลักอันหนึ่งของการเมืองไทยนี้เคยถูกวิเคราะห์ว่าเข้าสู่ช่วงการเปลี่ยนแปลงสำคัญในยุคสมัยของทักษิณ ชินวัตร แต่เมื่อคสช.เข้ามาสู่อำนาจก็กำลังปรับเปลี่ยนไปอีกครั้งหนึ่ง โดยที่นัยยะของการเปลี่ยนแปลงครั้งหลังนี้ยังไม่ได้ถูกวิเคราะห์ไว้มากนัก

บทความชิ้นนี้จะเริ่มจากการเล่าถึงเส้นทางของสวัสดิการประชารัฐ โดยจะวิเคราะห์ถึงที่มาและลักษณะสำคัญของชุดนโยบายนี้ จากนั้นบทความจะลองเสนอบทวิเคราะห์เบื้องต้นว่าสวัสดิการประชารัฐกำลังสร้างการเปลี่ยนแปลงอะไรในความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างรัฐและชนบทไทย รวมถึงนัยยะของการเปลี่ยนแปลงนี้ต่อคนชนบทคืออะไร

เส้นทางของสวัสดิการประชารัฐ

ก่อนจะมาถึงสวัสดิการประชารัฐ นโยบายสวัสดิการของไทยมีเส้นทางที่ผกผัน ผูกพันอยู่กับความสัมพันธ์ที่ปรับเปลี่ยนไปมาระหว่างรัฐและชนบท อาจกล่าวได้ว่าความสนใจในนโยบายสวัสดิการเกิดขึ้นอย่างชัดเจนเป็นครั้งแรกหลังการเปลี่ยนแปลงการปกครอง 2475 โดยเค้าโครงเศรษฐกิจของปรีดี พนมยงค์ ได้แสดงความพยายามในการสร้างระบบที่รัฐเข้ามีบทบาทแก้ปัญหาปากท้องของชาวนาในชนบท ซึ่งถูกมองว่าเป็นกลุ่มคนยากจนหลักของประเทศ

แต่เพียงไม่นาน การเข้าสู่สงครามโลกครั้งที่สองและการเมืองภายใต้สงครามเย็นก็ได้เข้ามาสร้างบริบทใหม่ สวัสดิการที่เกิดขึ้นในยุคเผด็จการของจอมพล สฤษดิ์ ธนะรัชต์ เรียกได้ว่าเป็นสวัสดิการแบบลดทอน (minimalist welfare) สะท้อนความสัมพันธ์ที่รัฐหันไปมุ่งขูดรีดชาวนาและชนบทเพื่อผันส่วนเกินทางเศรษฐกิจไปสนับสนุนการเติบโตของทุนเอกชนและคนเมือง

สภาพสวัสดิการที่ขาดหายบนความสัมพันธ์แบบที่รัฐขูดรีดชนบทนี้เริ่มเปลี่ยนแปลงเมื่อระบบเผด็จการทหารต้องเผชิญความท้าทายจากขบวนการเคลื่อนไหวทางสังคมในยุคคริสตทศวรรษ 1970s และยิ่งเมื่อการเมืองไทยเปลี่ยนแปลงไปเป็นประชาธิปไตยมากขึ้นในช่วง 1990s สวัสดิการก็เข้าสู่ช่วงขยายตัว พร้อมกับที่รัฐปรับบทบาทอย่างชัดเจนมาเป็นผู้ที่อุดหนุนชนบท การปรับเปลี่ยนบทบาทนี้เกิดขึ้นอย่างชัดเจนหลังจากรัฐบาลทักษิณได้เข้าสู่อำนาจ โดยรัฐบาลทักษิณหันมาเน้นนโยบายช่วยเหลือเกษตรกร เช่น อุดหนุนราคาสินค้าเกษตร พักหนี้เกษตรกร อีกทั้งยังมีชุดนโยบายอื่นที่คนชนบทได้ประโยชน์มากเช่น กองทุนหมู่บ้าน และหลักประกันสุขภาพถ้วนหน้า

นโยบายเหล่านี้กลายมาเป็นหัวใจหลักของความสำเร็จทางการเมืองของทักษิณ และแนวทางที่คล้ายกันก็ยังถูกสืบทอดมาสู่พรรคการเมืองที่โยงใยกับเขาในเวลาต่อมา เช่น พรรคพลังประชาชนและพรรคเพื่อไทย อย่างไรก็ตาม ความสำคัญของนโยบายเหล่านี้ก็มาพร้อมกับแรงต่อต้านที่สะสมขึ้นเรื่อยๆ โดยเฉพาะจากพลังทางสังคมหลากหลายที่รวมตัวกันต่อสู้กับรัฐบาลทักษิณและยิ่งลักษณ์ ที่มักจะตีตรานโยบายสวัสดิการในยุคทักษิณและยิ่งลักษณ์ในเชิงลบว่าเป็นนโยบายแบบ “ประชานิยม” แรงต่อต้านนี้เองเป็นพลังสำคัญที่เชื่อมโยงไปสู่การเกิดขึ้นและพัฒนาการของนโยบายสวัสดิการแบบ “ประชารัฐ”

แรงผลักดันจากการต่อต้านประชานิยม ส่งอิทธิพลต่อไปถึงพัฒนาการของสวัสดิการประชารัฐในหลายทาง เช่น การมุ่งโจมตีนโยบายสวัสดิการที่ริเริ่มมาก่อนหน้าว่าใช้งบประมาณอย่างสิ้นเปลือง สร้างความเสี่ยงทางการคลัง ส่งผลให้สวัสดิการประชารัฐต้องพยายามเสนอแนวทางที่ต่างออกไป โดยคสช.ได้พยายามลดความสำคัญของนโยบายอุดหนุนภาคการเกษตร ยกเลิกโครงการช่วยเหลือผู้มีรายได้น้อยเช่น รถเมล์ รถไฟฟรี นอกจากนี้ ยังมักจะแสดงจุดยืนวิพากษ์ถึงความสิ้นเปลืองงบประมาณของนโยบายหลักประกันสุขภาพถ้วนหน้า ดังที่พลเอกประยุทธ์ จันทร์โอชา ในฐานะหัวหน้าคสช.และนายกรัฐมนตรีเคยกล่าวไว้ว่า “งบประมาณสาธารณสุขมันไม่พอ เพราะท่านไปทำ … รักษาทุกโรคยังไงเล่า มันเป็นไปได้ไหมเล่า … มันเป็นโครงการประชานิยม แต่มันเป็นธรรม ประชาชนได้รับ ผมก็ไปอะไรไม่ได้ แต่เรามีความพร้อมหรือยัง เฉลี่ยแล้วคนละ 2,900 บาทนี่มันพอไหม … รักษาพอไหม โรงพยาบาลเขาจะรับไหวไหม รักษาทุกโรคเนี่ย … โรงพยาบาลเขาก็จะเจ๊ง”

ลักษณะสำคัญของสวัสดิการประชารัฐ

พัฒนาการสำคัญที่บ่งชี้แนวทางที่แตกต่างของสวัสดิการประชารัฐนั้น ถูกสะท้อนได้จากผลผลิตสำคัญในยุคคสช. ก็คือ “โครงการบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐ” หรือที่มักจะถูกเรียกกันในชื่อของบัตรคนจน ทุก ๆ ต้นเดือน ผู้ที่ผ่านการคัดกรองฐานะความยากจนและได้ถือบัตรดังกล่าวจะได้รับวงเงินสำหรับซื้อของในร้านธงฟ้าประชารัฐ 200-300 บาท และการช่วยเหลืออื่น ๆ เช่น ค่าโดยสารสำหรับบริการขนส่งสาธารณะ ส่วนลดค่าก๊าซหุงต้ม ทั้งนี้ในช่วงหลังยังมีการเพิ่มเงินอุดหนุนสำหรับคนที่เข้าร่วมโครงการฝึกงานกับภาครัฐ รวมถึงเพิ่มเงินสำหรับคนพิการ เกษตรกร ผู้สูงอายุ เป็นต้น

ผลผลิตเช่นโครงการบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐนี้ช่วยบ่งบอกถึงลักษณะสำคัญสามประการของสวัสดิการประชารัฐได้ดังนี้

ประการแรก สวัสดิการประชารัฐเป็นสวัสดิการที่หันไปเน้นแนวทางการช่วยเหลือแบบเจาะจงที่คนจน (poverty-targeting) บัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐถือเป็นโครงการสวัสดิการแรกของประเทศไทยที่นำสวัสดิการแบบเจาะจงที่คนจน ผ่านกระบวนการพิสูจน์ฐานะความยากจน (mean-tested) มาใช้ในระดับประเทศ คนที่จะได้รับการช่วยเหลือผ่านบัตรนี้จะต้องผ่านการลงทะเบียนแสดงฐานะตนเองว่ามีรายได้ไม่เกิน 100,000 บาทต่อปี และผ่านการตรวจสอบฐานะการครอบครองทรัพย์สิน ว่ามีทรัพย์สินทางการเงินไม่เกิน 100,000 บาท และมีที่ดินไม่เกิน 10 ไร่ การหันมาให้สวัสดิการเฉพาะกับคนที่มีฐานะยากจนนี้ยังเป็นทิศทางที่สอดคล้องกับยุทธศาสตร์ 20 ปีที่คสช.ได้วางเอาไว้ ซึ่งระบุว่าเป้าหมายของการสร้างสวัสดิการสนับสนุนโอกาสนั้นควรจะเจาะจงไปที่ประชากรร้อยละ 40 ที่มีรายได้ต่ำที่สุด

จะสังเกตได้ว่าทิศทางไปสู่การเจาะจงให้สวัสดิการกับคนจนนี้เป็นการตอบสนองต่อมุมมองที่ต้องการสร้างประสิทธิภาพทางการคลังให้กับนโยบายสวัสดิการ นอกจากนี้ รูปแบบการให้สวัสดิการแบบเจาะจงที่คนจนยังมีแนวโน้มสูงที่จะขยายไปสู่สวัสดิการในรูปแบบอื่นด้วย ตัวบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐเองก็ถูกออกแบบมาให้มีช่องทางที่สามารถเพิ่มการอุดหนุนในลักษณะอื่นเข้าไปได้อีกมาก เช่น การให้สวัสดิการคนชรา รวมถึงสวัสดิการสนับสนุนการเลี้ยงดูบุตร ซึ่งเมื่อสวัสดิการเหล่านี้ถูกนำมากระจายผ่านบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐก็จะมีลักษณะเป็นสวัสดิการที่ให้เฉพาะคนจนไปโดยปริยาย

ประการที่สอง สวัสดิการประชารัฐโยงใยอยู่กับความต้องการกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจฐานราก สภาพเศรษฐกิจนับตั้งแต่คสช.เข้าสู่อำนาจนั้นประสบภาวะชะลอตัวอย่างต่อเนื่องมาเกือบตลอด โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในภาคเกษตรที่ประสบปัญหาราคาสินค้าตกต่ำ ทำให้อัตราการเติบโตติดลบตั้งแต่ปี 2014 ถึง 2016 ส่งผลต่อเนื่องให้รายได้ของคนในชนบทลดลง

ในบริบททางเศรษฐกิจเช่นนี้ การเกิดขึ้นของบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐจึงถูกวางเป้าหมายไว้อีกประการว่าจะเป็นเครื่องมือหนึ่งที่เข้ามาช่วยกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจฐานรากได้ ผ่านการอุดหนุนเงินไปเป็นกำลังซื้อให้กับกลุ่มผู้มีรายได้น้อยโดยเฉพาะในชนบท และหวังให้เกิดการใช้จ่ายหมุนเวียนต่อไปสู่คนกลุ่มอื่น ๆ นอกเหนือจากเงินอุดหนุนที่ให้ผู้มีบัตรใช้จ่ายเป็นประจำแล้ว ยังมีมาตรการกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจอีกหลายต่อหลายครั้งที่ใช้บัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐเป็นตัวกลาง เช่น มาตรการกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจปลายปี 2018 โดยให้กดเงินสดจากบัตรไปใช้จ่ายได้ และในปี 2019 ก็กำลังมีการพิจารณาเพิ่มเงินค่าเดินทางไปท่องเที่ยวสำหรับผู้มีบัตรให้คนละ 1,500 บาท

ประการสุดท้าย สวัสดิการประชารัฐสะท้อนบทบาทที่มากขึ้นของความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างรัฐและทุนใหญ่ ตั้งแต่จุดเริ่มต้นของโครงการประชารัฐ บทบาทของทุนใหญ่ในประเทศไทยในการเข้าร่วมมือกับรัฐบาลคสช.ก็ถูกแสดงให้เห็นอย่างชัดเจน คณะกรรมการประชารัฐที่รัฐบาลคสช.ตั้งขึ้นมาขับเคลื่อนโครงการพัฒนาหลากหลายด้านนั้นประกอบไปด้วยตัวแทนจากภาคเอกชนถึงร้อยละ 73 โดยตัวแทนเหล่านี้ต่างก็มาจากบริษัทใหญ่ เช่น เจริญโภคภัณฑ์ ทรู คอร์เปอเรชัน มิตรผล ปตท. และปูนซีเมนต์ไทย

สำหรับโครงการบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐเองอาจไม่ได้เชื่อมโยงกับบทบาทของทุนใหญ่โดยตรง แต่ก็มีข้อสังเกตได้ว่าตัวบัตรสวัสดิการแห่งรัฐในช่วงเริ่มแรกนั้นถูกจำกัดให้ซื้อสินค้าได้กับร้านค้าบางร้านเท่านั้น จนนำไปสู่ข้อวิพากษ์ว่าตัวนโยบายอาจจะมีการเอื้อประโยชน์ให้กับทุนใหญ่ที่เข้าร่วมโครงการประชารัฐ แม้ข้อจำกัดนี้จะถูกอธิบายว่าได้ลดบทบาทลงไปในภายหลัง แต่บริบทแวดล้อมการกำหนดนโยบายที่ทุนใหญ่เข้ามามีบทบาทมากขึ้นก็ยังคงมีความสำคัญอยู่

นัยยะของสวัสดิการประชารัฐ

แอนดรูว์ วอล์คเกอร์ ได้อธิบายไว้ใน “ชาวนาการเมือง” (Thailand’s Political Peasants) ผลงานชิ้นสำคัญของเขาถึงการเปลี่ยนแปลงในความสัมพันธ์ระหว่างรัฐและชนบทในช่วงทักษิณ ว่าเกิดขึ้นระหว่างรัฐที่หันมาทำหน้าที่อุดหนุนชนบท และชาวนาผู้ซึ่งผ่านการพัฒนาทางเศรษฐกิจจนมีฐานะแบบรายได้ปานกลาง

วอล์คเกอร์หยิบเอาแนวคิด สังคมการเมือง (political society) มาอธิบายสังคมชนบทไทยที่ปรับเปลี่ยนไปภายใต้ความสัมพันธ์ใหม่นี้ โดยเล่าถึงความต้องการพื้นฐานของคนชนบทว่าไม่ใช่เรื่องของการสมยอมหรือการมุ่งต่อต้านการขูดรีดของรัฐอีกต่อไป หากแต่สิ่งที่พวกเขาแสวงหาภายใต้บริบทที่รัฐเข้ามาทำหน้าที่อุดหนุนก็คือการเข้าไปมีปฏิสัมพันธ์กับรัฐเพื่อดึงเอาทรัพยากรและอำนาจมาสร้างประโยชน์กับตนเอง และความสัมพันธ์กับรัฐแบบใหม่นี้เองยังเป็นฐานทางอัตลักษณ์ใหม่ให้กับพวกเขา

เส้นทางที่คนชนบทไทยในสังคมการเมืองจะเข้าไปปฏิสัมพันธ์กับรัฐได้นั้นมีหลากหลาย ผ่านทางนโยบายและโครงการพัฒนาหลายรูปแบบที่ตัวแทนอำนาจรัฐได้นำเข้าไปโยงกับกลุ่มคนที่แตกต่างกันในชนบท แต่ภายใต้ความสัมพันธ์แบบนี้ นโยบายก็มักจะออกมาขาดระบบระเบียบและปล่อยให้สายสัมพันธ์ส่วนตัวเข้ามามีบทบาท จนทำให้คนชั้นกลางในเมืองมักจะมองนโยบายเหล่านี้ว่าขาดความก้าวหน้าของการเมืองสมัยใหม่ ดังที่สะท้อนจากเสียงวิพากษ์ของพวกเขาต่อนโยบายประชานิยมของทักษิณ

สวัสดิการประชารัฐได้เข้ามาปรับเปลี่ยนความสัมพันธ์เช่นนี้ไปอย่างไร? หากเส้นทางของสวัสดิการประชารัฐดำเนินต่อไปและลักษณะต่างๆที่ได้กล่าวไว้ข้างต้นถูกผลักดันให้ชัดเจนขึ้น ก็คงจะไม่เกินเลยนักที่จะตั้งข้อสังเกตว่าสังคมชนบทไทยภายใต้อิทธิพลของสวัสดิการประชารัฐกำลังเคลื่อนออกจากสภาพของชาวนาการเมือง

จริงอยู่ที่รัฐไทยยังทำหน้าที่อุดหนุนชนบท ถึงจะไม่ชัดเจนเท่าแต่ก่อน แต่ความสัมพันธ์ที่มาพร้อมกับการอุดหนุนของสวัสดิการประชารัฐก็ดูจะต่างไปจากแบบที่คนชนบทได้เข้าไปสร้างความสัมพันธ์กับรัฐเพื่อดึงเอาประโยชน์มาสู่ตนเอง แต่เป็นความสัมพันธ์ใหม่ที่รัฐและระบบราชการใช้อำนาจและความเชี่ยวชาญเข้าไปจัดสรรการอุดหนุนคนยากจน ทั้งสายสัมพันธ์ผ่านทางนโยบายและโครงการที่หลากหลายก็ยังมีแนวโน้มจะถูกแทนที่ด้วยสายสัมพันธ์หลักของกระบวนคัดกรองและกระจายประโยชน์สู่เฉพาะคนจน

อาจกล่าวได้ว่า สวัสดิการประชารัฐกำลังสร้างการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่ทำให้คุณค่าและความสำคัญของอัตลักษณ์ “ชาวนา” ในทางการเมืองของคนชนบทถดถอย และสร้างอัตลักษณ์ใหม่ในการเป็น “คนจน” เข้าแทนที่

นัยยะสำคัญของการเปลี่ยนแปลงที่สวัสดิการประชารัฐสร้างขึ้นกับชนบทไทยคืออะไร บทความนี้จะขอลองวิเคราะห์เบื้องต้นในสองแง่มุม คือ (1) การเปลี่ยนแปลงในภาคการเกษตร และ (2) การลดความเหลื่อมล้ำที่คนชนบทต้องเผชิญ

สำหรับการเปลี่ยนแปลงในภาคการเกษตรนั้น สิ่งทีวอล์คเกอร์ระบุไว้ว่าเป็นผลของสังคมชนบทแบบชาวนาการเมืองก็คือการที่บทบาทของรัฐกลายเป็นกลไกสำคัญที่ช่วยรักษาสังคมชาวนาเอาไว้ ภาพของภาคการเกษตรตั้งแต่สมัยทักษิณจนมาถึงยิ่งลักษณ์ (ปี 2000-2014) ที่ทั้งขนาดการผลิตและจำนวนแรงงานในภาคการเกษตรแทบไม่ได้หดตัวลง ก็ค่อนข้างตรงกับข้อสังเกตนี้ (ดูรูปประกอบด้านล่าง)

มูลค่า GDP ภาคการเกษตรและจำนวนผู้มีงานทำในภาคการเกษตร ที่มา: ธนาคารแห่งประเทศไทย

อย่างไรก็ตาม ผลจากช่วงเวลาของคสช.และสวัสดิการประชารัฐ อาจทำให้กระบวนการรักษาสังคมชาวนาที่ดำเนินมาต้องจบลง ภาคการเกษตรอาจกลับเข้าสู่เส้นทางของการหดตัวอีกครั้ง ทั้งนี้สภาพเศรษฐกิจที่ซบเซาในชนบท ปัญหาราคาสินค้าเกษตรตกต่ำ รวมถึงการอุดหนุนที่ลดลง ต่างก็แสดงว่าการอยู่ในภาคการเกษตรนั้นได้กลายเป็นเรื่องที่ยากขึ้นสำหรับคนชนบทในปัจจุบัน

สำหรับด้านความเหลื่อมล้ำ อันเป็นปัญหาสำคัญสำหรับคนชนบทที่ได้ยกระดับฐานะทางเศรษฐกิจของตนเองจนพ้นความยากจนมาแล้ว สวัสดิการประชารัฐเป็นชุดนโยบายที่กำลังเข้ามามีบทบาทสำคัญต่อการลดความเหลื่อมล้ำที่พวกเขาต้องเผชิญ

แม้สวัสดิการประชารัฐเองจะได้รับการออกแบบผ่านแนวคิดว่าการช่วยเหลือแบบเจาะจงไปที่คนจนจะทำให้กระบวนการผันทรัพยากรไปยกระดับฐานะของคนยากจนมีประสิทธิภาพมากขึ้น เพิ่มศักยภาพในการลดความเหลื่อมล้ำ อย่างไรก็ตาม ลักษณะสำคัญบางประการของสวัสดิการประชารัฐก็อาจทำให้การจะบรรลุเป้าหมายเช่นนี้ไม่ใช่เรื่องง่าย

ดังที่กล่าวไว้ข้างต้นว่าสวัสดิการประชารัฐนั้นถูกขับเคลื่อนมาจากกระแสต้านประชานิยม สภาพเช่นนี้อาจกลับไปเป็นเงื่อนไขที่สร้างข้อจำกัดต่อโอกาสการขยายตัวและเพิ่มศักยภาพของสวัสดิการประชารัฐได้ เนื่องจากทัศนคติจากคนหลายกลุ่มต่อนโยบายสวัสดิการเพื่อคนจนนั้นยังอยู่ในแง่ลบ การหันมาให้สวัสดิการเฉพาะเจาะจงที่คนจนก็เลี่ยงได้ยากที่จะต้องเผชิญทัศนคติทางลบต่อไป และยังอาจรุนแรงขึ้นเสียด้วยซ้ำหากรัฐมุ่งหน้าขยายสวัสดิการในรูปแบบใหม่นี้

นอกจากนี้ การที่เป้าหมายของสวัสดิการประชารัฐยึดโยงอยู่กับการสร้างประสิทธิภาพทางการคลังและการกระตุ้นเศรษฐกิจ ก็อาจทำให้เป้าหมายการลดความเหลื่อมล้ำนั้นไม่มีความชัดเจนและโดนแทรกแซงได้ง่ายโดยเป้าหมายอื่น และท้ายที่สุด หากมองไปที่ภาพใหญ่ของสภาพแวดล้อมในการกำหนดนโยบาย ที่ความสัมพันธ์หลักได้เกิดระหว่างรัฐที่ขาดความเป็นประชาธิปไตยและทุนใหญ่ ก็ยังชวนให้คิดได้ว่าสภาพเช่นนี้จะเอื้ออำนวยให้เกิดการผลักดันไปสู่การลดความเหลื่อมล้ำอย่างจริงจังได้อย่างไร

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss