How moderate are Indonesian Muslims compared to Muslims in other countries? This is a question that has intrigued scholars and observers alike. Various interested parties have expressed optimism on the moderate nature of Indonesian Muslims or sounded warnings that the moderation is crumbling, if ever there in the first place.

To give some examples, President Joko Widodo and his challenger in the upcoming election Prabowo Subianto position themselves among the optimists. Marcus Mietzner and Burhanuddin Muhtadi are more cautiously optimistic, noting that while conservative attitudes are not becoming more popular, conservative Muslims are now better organised, increasing their political influence. Andreas Harsono, a human rights activist, is downright critical, noting that Indonesia is no model for Muslim democracy, a sentiment shared by many following the religious mobilisation surrounding the 2017 Jakarta election.

The privileges and positive spotlight of being regarded as an example of moderation aside, I argue that the current debate on how moderate Indonesia is has missed two important points. First, claiming a society as moderate requires a point of comparison: moderate compared to what? It seems that whenever we are talking about Indonesia’s moderation, we tend to compare it to countries like Afghanistan and Pakistan—certainly not a high bar to claim moderation. Second, claiming a society as moderate requires sharing a similar standard of assessment. Two observers are likely talking past each other if one claims that Indonesia is moderate because it does not base its laws on Islamic law, and the other that Indonesia is conservative because of the growing persecution of religious minorities.

My analysis here is an effort to improve these two limitations. I compare Indonesian Muslims to Muslims in other Muslim-majority countries and use a similar standard to compare these countries around the world. This exercise will in turn enable us to answer in a more comprehensive and objective manner how moderate Indonesian Muslims really are.

Measuring moderation

I define conservatism as a preference for social norms, traditions, or orders that is supportive of the confluence of politics and religion consistent with traditional Islamic values, following a similar definition from Lisa Blaydes and Drew Linzer. I refrain from entering the normative debate about whether Islamic conservatism does or does not represent the “true” Islam; the focus here is to compare Muslim countries based on a score of how socially, religiously, and politically conservative their Muslim populations are.

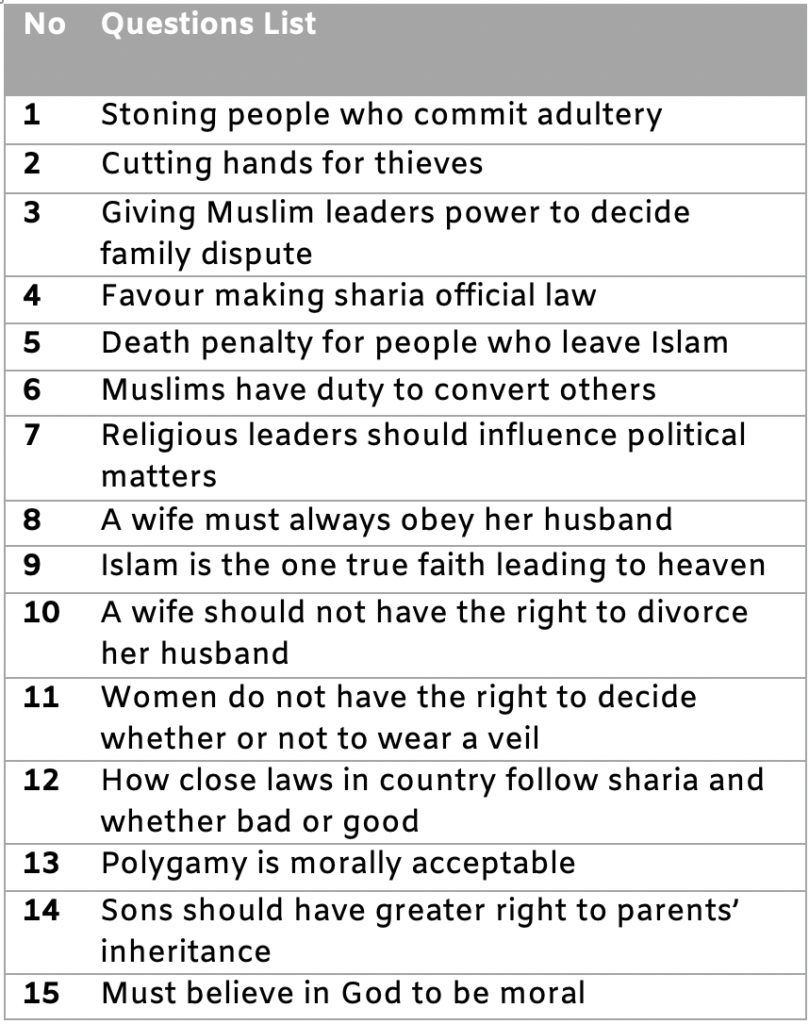

To construct just such a score, I used a dataset developed by the Pew Research Center. Between 2011 and 2012, Pew commenced a global study on the World’s Muslims, surveying 32,604 Muslims in 26 countries on various topics ranging from religious practice to political attitudes. I went through the questionnaire and identified 16 questions that on face value (1) pertain to attitudes or opinions on social issues, (2) have social components in the sense that the question is related to people, society, or social groups, (3) are related to Islamic conservatism; and (4) were asked in at least half of the countries studied.

These criteria helped to exclude demographic and personal history questions, as well as questions that are related to faith doctrines (e.g., whether one believes in one God), questions that are related to frequency of religious practice (e.g., how often one prays), and country-specific questions. Respondents were asked to indicate how much they agree or disagree with each of the statements, and I coded the responses so that higher scores represent a stronger agreement with the questions.

Having identified the most relevant questions (see left), the next task is to create an aggregate score that represents each respondent’s level of conservatism. There are different ways to do this. The most common approach would be to simply take the average of each respondent’s responses across the questions. An obvious limitation of this strategy is that it would assume that all the questions listed above are equally important indicators of Islamic conservatism. On the other hand, we know that some of the above questions are more closely related to Islamic conservatism than the others. For example, respondents who agree that converting from Islam must be punishable by death (Item 5) should be considered more conservative than those who simply agree that one must believe in God to be moral (Item 15).

My approach is to use what is called a Bayesian item-response method (or Bayesian IRT; specifically, I use a graded-response IRT model). A detailed discussion of the nature and benefits of Bayesian statistics can’t be presented here, but the important thing is that the IRT approach I use has three advantages compared to the traditional aggregation methods (e.g., averaging across questions), or the simple practice of presenting only descriptive statistics.

First, an IRT approach assigns greater weight to questions that better separate conservative and more moderate respondents. Second, an IRT approach handles missing data well: respondents across the countries do not have to answer similar questions, as long as there are still some questions that they all answer. This is a particularly useful property in analysing a global dataset like Pew’s as some questions in Table 1 were not asked in certain countries. Third, as an IRT approach produces a conservatism score at the individual level, we can aggregate this score to the country-level and reconstruct the distribution of respondents in each country. The latter exercise is particularly interesting because it will allow us to estimate the relative proportion of conservative and moderate respondents in each country.

Where does Indonesia fall?

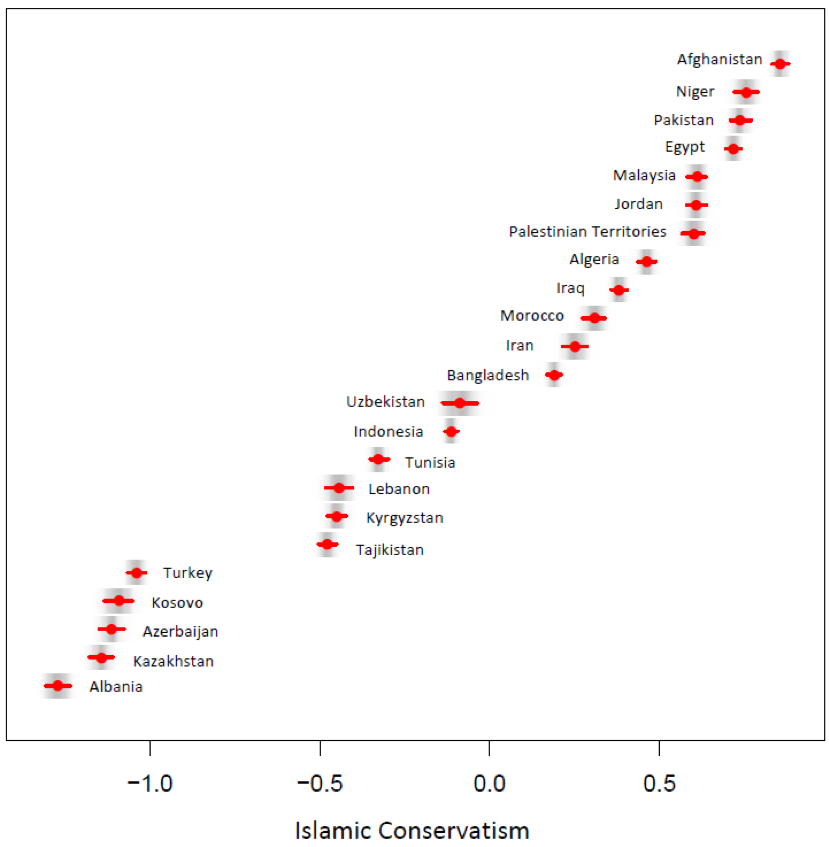

Using the Pew dataset, I estimated the conservatism scores of 29,534 Muslim respondents in 23 Muslim-majority countries (excluding Thailand, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Russia, where Pew surveyed the large Muslim minorities there). During the IRT estimation process, I set the mean of the conservatism scores to be zero with standard deviation one.

Figure 1 presents results from the IRT approach. For each country, I present a point estimate (i.e., the country’s most likely conservatism score), a 95% credible interval (i.e., the top 95% most likely values for the country’s conservatism score), and a density plot, in the form of black shadow in the background, that represents all possible conservatism scores for that country generated during the estimation process.

Figure 1. [Click to Enlarge] Levels of Islamic Conservatism in 23 Countries (Higher Scores Mean More Conservative)

Where is Indonesia, our country of interest? Most interestingly, Indonesia is located almost right in the middle along with Uzbekistan. Indonesia is much less conservative than its neighbour Malaysia, but is more conservative than Lebanon or Turkey. Broadly speaking, Indonesian Muslims’ social and political attitudes are not as heavily influenced by their religious values as Malaysian Muslims are, but they are also not as secular as their Turkish counterparts. Perhaps, by rejecting both extreme conservatism and extreme secularism or liberalism, Indonesian Muslims indeed deserve their reputation as “moderates”.

But these figures do not tell us about the proportion or distribution of moderates and conservatives within countries. Take Indonesia, for instance. Does that country have a mean of zero because it has a normal or bell-shaped curve with relatively equal numbers of liberals and conservatives, or because it has a right-skewed distribution with many liberals on the left, and a small number of conservatives on the right who are so extreme that they significantly push the country’s conservatism score upward?

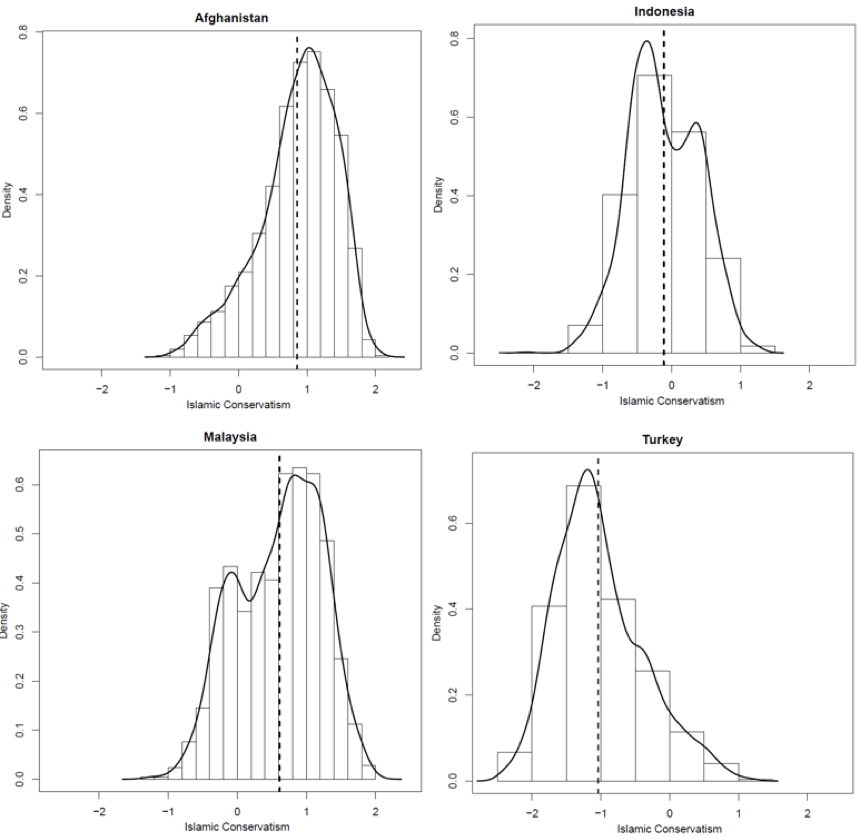

Recall again that our IRT approach produces conservatism scores at the individual level. This means that we can plot the distribution of respondents along a spectrum of conservatism in each country. Figure 2 below presents the density estimates of respondents in Afghanistan, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Turkey for comparison. The dashed line represents the country’s mean conservatism score and higher bars represent higher density (i.e. more respondents) for that particular conservatism level. Also recall that I already set the scores to have a mean of zero. So, broadly speaking, conservatism scores greater than zero can be considered conservative and scores less than zero are liberal or secular.

Let’s look at Afghanistan and Turkey first. Afghanistan is the most conservative country in our analysis and Turkey is one of the least conservative. We see in Afghanistan that the majority of respondents are indeed very conservative (scoring higher than one). In contrast, the majority of respondents in Turkey are very liberal or secular (scoring less than minus one).Indonesia’s neighbour Malaysia is also a very conservative country according to Figure 1. From Figure 2 we know that most Malaysian respondents are indeed conservative (scoring around one), but a considerable segment of the population are actually quite moderate (scoring zero). It is just that these Malaysian moderates are outnumbered by the conservatives.

Who’s running on Islam in Indonesia?

A look at the religious rhetoric contained in parliamentary candidates’ campaign platforms.

Moderation as a challenge

Based on these results, Indonesian Muslims perhaps truly deserve to be recognised as moderates. But considering that the data is seven years old, the biggest question here is perhaps how would the picture would look now. Is Indonesia still in the middle? Unfortunately, we will have to wait until more recent data become available.

One thing is clear, however: none of this is set in stone. Societies change and they can move to be more conservative or more liberal. In the past seven years, we have seen Erdogan championing a version of Islamic conservatism in Turkey, and populism rising in many parts of the world. Indonesians have experienced first-hand the unprecedented religious mobilisations during the 2017 Jakarta election and their lasting impacts on the upcoming presidential election. If Indonesia wants to maintain its position as an example of moderation, then it has to do better in managing its religious divides that seem to be growing every day, fuelled by divisive rhetoric of certain political and religious elites. It has to resist the push to infuse more religion into public life, lest it see itself being unwillingly dragged to the right. The finding presented here is not a vindication of Indonesia’s success in attaining moderation: it offers a challenge to maintain it.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss