Over recent decades, the nature of Indonesia-related expertise in Australian universities has changed dramatically. During the late 1980s the arts faculty in which I was an undergrad included many scholars with expertise in the symbolic dimensions of Indonesian social and political life. They studied the history, performance genres, literature, music and social conditions of Indonesian communities.

After retirement, those scholars were not replaced by academics with the same specialisations, and the focus of Indonesia-related expertise has shifted. In the present, academic activity about Indonesia is concerned more with the material conditions confronted by Indonesian individuals and groups, as well as the policies and infrastructures that bear upon them. In other words, the focus of scholarly expertise has shifted from knowledge of the symbolic part of Indonesian life to a concern with material and social wellbeing and the governance systems that might ensure that.

This shift brings the academy in step with what I observe to be a distinctive trait of Australia’s imagining of Indonesia: Australians like to construct Indonesia as a recipient of assistance. If Australians have given a brand label to Indonesia, it is “brand needy”. Our university departments are now dedicated to this construction, working for the alleviation of problems faced by Indonesians in the fields of the environment, disability, health, governmental capacity, policy formulation. It seems that ”helping Indonesia” is now more prominent than ”learning about Indonesia”.

As the chair of a program responsible for teaching Indonesian language and studies, it strikes me that there is a connection between this tendency of Australian public discourse and the low levels of interest in Indonesia amongst young people.

The depth of the problem emerges through comparison with other language and studies programs. On looking sideways at my four colleagues in the French language program of the G8 university where I teach, I observe that one of these is expert in French contemporary philosophy, literature and theology. A second researches cinema, cultural histories of Paris, art, fashion, and celebrity studies. A third researches French Literatures with attention to race and queer theory. A fourth studies sub-Saharan Francophone literature and French postcolonial/decolonial theory.

All their expertise is focused on efforts to understand the symbolic dimensions of French societies. Their scholarly activities do not show any inclination towards helping French societies, but proceed from a position of respect and deference for French civilisation (in the wider sense). And student interest in studying French is high. In semester 1 of 2023, the unit for students wishing to study French with no existing capability attracted 120 students. The equivalent unit in Indonesian attracted 16, and that figure is a high one when compared with years before that.

The figures were not supposed to be like this. Since the 1990s, Australian policymakers, with broad public support, have attempted to raise Asia literacy amongst Australians. In the case of Indonesia literacy, the results have not been impressive. Given the broad support from government and the public, we should ask what has happened?

The tendency to construct Indonesia as needy has little to do with Indonesia. It has its origins in the culture and public politics of white Australia. A recent study by Agnieszka Sobocinska reveals this culture and public politics. She made a documentary study of programs initiated in Western societies that enabled volunteers to give service in Asia. Sobocinska labels this the “humanitarian-development complex”. Australia features heavily in this book, for Australia’s ”Volunteer Graduate Scheme”, which commenced in 1951, was ”the first modern development volunteering endeavor”.

Sobocinska found that volunteering programs gave negligible or non-existent benefits to the host populations in the ”developing world”. What was very clear, however, was their groundings in the emerging public cultures of the societies from which the volunteers came. Two observations stand out among the conclusions of her study of media representations and public expression about development volunteering.

First, material and moral support for development volunteering came from across the spectrum of public contributors, reflecting a public consensus that ”underdeveloped” nations required help, and secondly, the volunteering subject came to be seen as a virtuous and commendable figure. The rationale for the program depended more on the desirable subjectivity created in media representations in the ”developed” country than in any benefit to be received in the host country. The neediness of the ”developing world” was to a degree created out of notions of virtue prevailing in Australian public life.

Sobocinska’s book reveals the difficulty of the problem we are facing here: the naturalness of the construction of our neighbours as needy. To take the position of helper seems so naturally to be the right thing to do, and the resolution of serious problems facing contemporary populations across the world is clearly a core mission of the modern university.

I have observed this difficulty previously in New Mandala when writing about the media’s coverage of animal cruelty in Indonesia. In that piece, I observed that Indonesia had become the prime source of Australia’s images of cruelty to animals. We all agree that action needs to be taken to prevent cruelty to animals, wherever it might happen. But as we continue to emphasise Indonesia as a place of cruelty to animals, the well-meaning people who travel there to confront the problem become more and more virtuous. Both examples indicate the mutually constitutive relationship: the construction of the needy volunteer piggybacks upon the construction of the needy recipient.

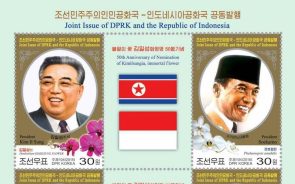

Indonesia and North Korea: warm memories of the Cold War

Friendly ties to Pyongyang have been an emblem of non-alignment for generations of Indonesian foreign policy makers.

In the contemporary university, these scholarly observations are marginalised or obscured by the pressing need to help. The construction of neediness has a power that can be seen in academic hiring practices. In an environment where such high importance is attached to specialised projects that help Indonesian communities’ material situations, it is becoming harder to rationalise the hiring of academics with specialisations in the symbolic.

When perceptions of neediness are so high, the study of the symbolic seems to stand in the way of the important project of helping. By giving support for the study of Indonesian history, literature, performance genres, music and social structures, we might appear to be preventing research that will be of benefit to Indonesia. In this way, construction of Indonesia as needy is perpetuated, and the emergence of alternate brands is prevented.

Based on my engagement with the beginning students in our program, it is clear that they do not enrol in our course because they wish to help Indonesia (although some of them might). Although I am drawing on intuitions rather than scientific findings here, their motivations appear to be similar to those of our beginning students of French: students of Indonesia are amazed by Indonesian history and culture, and are hungry for engagement with it, just as students of Beginners’ French are wanting to engage with French history, culture and thought.

But there are only 16 studying beginners’ Indonesian in comparison with 120 studying French. Could it be that our relentless construction of Indonesia as needing help might have to some degree shaped the national disposition towards Indonesia? And ought we pay attention to the importance of the academy as a resource for working against that construction?

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss