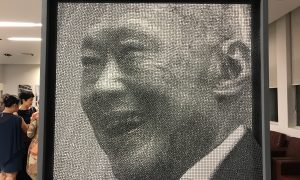

As official China celebrates the four decades of “reform and opening” that began in late 1978 to early 1979, it is instructive to recall the role Singapore played in this process. The fulsome eulogies for Lee Kuan Yew offered by Chinese officials in 2015, beginning with Xi Jinping himself (who has been noticeably less enthusiastic in his praise for Deng Xiaoping given China’s top leader’s “family feud” over who deserves the most credit for the reforms), are just the most obvious indication that Lee and the “Singapore model” more generally have played (quite literally) an oversized role in China’s rapid transition from Maoism to “Market-Leninism”. Appropriately, Lee was honoured late last year as one of the foreigners who helped China most in its reform process.

In November 1978 Deng, newly installed as China’s paramount leader, visited Singapore. Ostensibly the trip was part of a diplomatic campaign by China against what it considered a growing threat from Soviet-backed Vietnam. But in Singapore, Deng instead became obsessed with the city-state’s purported transformation from a backwater fishing village to a leading global city under Lee Kuan Yew and his People’s Action Party’s (PAP) rule.

In his welcoming remarks, Lee stressed that Singapore’s ethnic Chinese citizens were the sons and daughters of uneducated, landless peasants from Southern China, leading Lee to suggest, as former foreign minister George Yeo has recently phrased it, if Singapore with its “poorly-educated coolies could make good, how much better mainland China could be if the right policies were adopted.” Deng showed great respect for Lee (going so far as to not smoke in the presence of the fastidious Lee despite the Singapore leader providing him with a spittoon in a well-ventilated room) as he had inherited a broken system that he was quickly trying to fix. In his comments Deng endorsed the (exaggerated) story of Singapore’s miraculous metamorphosis.

Crucially, Deng and Lee developed a special relationship during Deng’s short visit. Both were anti-colonial leaders at the forefront of their countries’ revolutionary movements and committed to political order over chaos. Ezra Vogel, in his monumental 2011 biography of Deng, comments that:

“Deng admired what Lee had accomplished in Singapore, and Lee admired how Deng was dealing with problems in China. Before Deng’s visit to Singapore, the Chinese press had referred to Singaporeans as the ‘running dogs of American imperialism.’ A few weeks after Deng visited Singapore, however, this description of Singapore disappeared from the Chinese press. Instead, Singapore was described as a place worth studying .…. Deng found orderly Singapore an appealing model for reform, and he was ready to send people there to learn about city planning, public management, and controlling corruption.”

Unlike other Chinese party leaders and academics who, as Kai Yang and Stephan Ortmann have shown, were looking at a variety of potential models such as Sweden (seen then to represent a “‘third way’ between Communism and capitalism” and symbolising “the ideals of social equity and harmony”), Deng was single-mindedly focused on Singapore, a fascination that was initially quite idiosyncratic. He was searching for a model that both legitimated party rule and was adaptable to the country’s rapid industrialisation. Deng’s articulation of the “Four Cardinal Principles” in 1979 showed that he still adhered to party orthodoxy in regard to repressing political dissent and reaffirming the party’s monopoly on power. But Deng was also concerned with how the party could guide China through state-led capitalist growth. In this regard, Deng left little doubt his thinking was closer to Lee’s than Karl Marx’s.

Yet the example of Singapore became central to the Chinese regime’s efforts to legitimise authoritarian rule only after collapse of the Soviet Union and its Eastern European state socialist satellite states and the Tiananmen Square massacre. Deng’s endorsement of Singapore as a model during his early 1992 “southern tour”, undertaken to restart the reform process, led to an outbreak of “Singapore fever” and an obsession with learning from Singapore among Chinese governing elite and academics. In quick follow up to Deng’s praise, a high level Chinese Communist Party (CCP) delegation was sent to Singapore, which quickly produced by book about the city-state that was distributed to all party branches. Hundreds of official trips followed, with Singapore setting up various programs to accommodate the influx of Chinese visitors such as the “Mayor’s Class” at Nanyang Technological University, attended by thousands of mid-level mainland officials.

An authoritarian path to modernity

It has been difficult for China to find examples of a successful combination of centralised authoritarian rule with effective and corruption-free government in a modern society anywhere else in today’s world besides Singapore. Besides the tiny sultanate of Brunei, Singapore is the only high-income country with a non-democratic regime in East Asia and arguably the only clear case globally, as oil-dependent absolute monarchies are rich but not “modern” in most understandings of the term. China’s observers also tend to see Singapore as “Chinese” and Confucian-influenced (ignoring its distinctive national identity and multi-ethnic character), making it seem more culturally appropriate for emulation.

Although Singapore remains a stand-alone example of high income, non-petroleum reliant “authoritarian modernism”, there is historical precedent for the attempt to remain authoritarian while successfully modernising in East Asia. Framed this way, Singapore is much less a “lonely” example of authoritarian modernity than it is a continuation of a historical trend. The “Prussian path” of German authoritarian-led development was followed by Meiji reformers and this model was later diffused throughout East Asia. Singapore is a particularly important example of this phenomenon not only because it wanted to “learn from Japan” (a government campaign in the early 1980s in which Japan had served as an ideological device used to maintain political control and manage social change that accompanied the upgrading of the country’s economy) and constructed a reactionary culturalist discourse (the “Asian values” debate of the 1990s) to help justify continued electoral authoritarian rule, but also because it became the chief model for Deng’s post-Maoist developmentalist leadership.

The Philippines’ Chinese FDI boom: more politics than geopolitics

A common logic—play nice with Beijing, get investment—doesn't fit the facts in the Philippines.

This is not to say that no major efforts at policy transfer have been undertaken—they have, from high-level cooperation institutionalised in the Joint Council for Bilateral cooperation between Singapore and China to joint industrial park/eco-city projects and local cadres trained in Singapore. As Lim and Horesh suggest, cadres trained in Singapore are “encouraged to emulate and draw inspiration from key tenets” of public administration in the city-state, providing “inspiration for devising new regulatory solutions.” Yet Lim and Horesh are sceptical about how much policy replication actually occurs, a view shared by Alexius Pereira, who points to the serious problems faced by the joint Suzhou industrial park. Lim and Horesh see the lack of the rule of law in China as a key hindrance to grasping the true nature of the “Singapore model”, a point particularly relevant in the anti-corruption drive under Xi Jinping.

The chief “lesson” Chinese experts have derived from Singapore’s fight against corruption is the importance of a committed leadership. But this analysis ignores the significance of the rule of law in Singapore, despite its being a tool to “constrain dissent” and increase the PAP’s “discretionary political power”. Theoretically, the PAP is not above the law, while the CCP claims primacy over any laws (euphemistically called “rule by law”), with China’s top judge recently denouncing judicial independence as a “false Western ideal”. By viewing determined leadership as the main lesson from Singapore, while at the same time rejecting an effective and independent legal system which was key to the city-state’s success in combating corruption, the Chinese leadership has picked “lessons” that confirm their own policy style while ignoring others that could potentially raise critical questions about it.

In many important ways, from country size to political “DNA” (i.e. the legacies of totalitarianism in post-Mao China compared to Westminster-style parliamentary institutions in Singapore), the two nations are simply too different to allow for any meaningful policy transfer. Moreover, Chinese observers have largely seen what they want to see: a one-party state ruled by wise leaders and built on Confucian principles which is successful and legitimate.

Rather, the key significance of the Singapore model for China has been primarily as a form of ideological confirmation, as it has provided an alternative telos for China as it modernises. Singapore shows what China can become: a highly modern but still one-party state undertaking carefully calibrated reforms. Thus, small though it is, Singapore has played an outsised role in reinforcing the CCP’s leadership’s belief that it can avoid the “modernisation trap” and remain resiliently authoritarian during modernisation and even after it successfully modernises.

Xi Jinping and Lee Kuan Yew unveil a bust of Deng Xiaoping to be displayed in central Singapore, November 2011. (Photo: Xinhua)

Growing out of the “Singapore model”

But more recently China seems to have moved away from adopting Singapore’s “soft authoritarian” style of rule. A recent book by David Shambaugh claims that gradualist political reforms by Xi Jinping’s predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, albeit within a continued authoritarian framework, were “intended to open up the system with carefully limited political reforms,” seeking to “manage political change rather than resist it.” By contrast, Xi’s recent widespread crackdown on dissent has undermining hopes of further, however constrained, political liberalisation. Shambaugh regrets that Singapore’s semi-competitive system, with a dominant party legitimised through limited but significant popular participation, and whose power is constrained by the rule of law, is no longer considered relevant by the Chinese leadership.

Thus, China seems to be moving further away from rather than toward the Singapore model. At the same time, as China takes a more aggressive stance in its foreign policy, particularly the South China Sea, and becomes more confident of its own political and developmental success, its interest in Singapore, which has staked out an independent foreign policy that has sometimes angered the mainland, has declined. After many years in which officials offered a codified version of the “Singapore story” to Chinese observers, Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong recently described the island state as little more than a “bonsai tree model of what China is” that might be “intriguing to scrutinise” but from which is hard for a gigantic country like China to draw lessons. Seemingly consigned to a historical period of conservative reformism in China, the “Singapore model” now appears to represent a path not taken by the mainland’s hard-line leadership.

This essay draws extensively from the author’s Authoritarian Modernism in East Asia (Palgrave 2019).

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss