There has long been a lively debate about the origins of the Rohingya Muslims—and it’s far from clear-cut. Active Rohingya campaigning is a relatively recent phenomenon, aiming to establish a separate state in Myanmar rather than seek outright independence.

Yet throughout time, the Rohingya and their political goals have not been taken seriously. When Burma progressed towards independence in 1948, the Rohingya failed to efficiently collectivise and represent their political aspirations, instead seeking ambiguous terms such as “social and economic development”, or even expressing their aims in conjunction with other political organisations.

In fact, Myanmar’s political consensus on the Rohingya has always been questionable. The attitudes of Buddhist authorities have been inconsistent—sometimes appearing to recognise the Rohingya as citizens in specific practical cases, such as paying taxes, voting in elections before 2015, etc—while at other times, denying the Rohingya temporary residence claims outright.

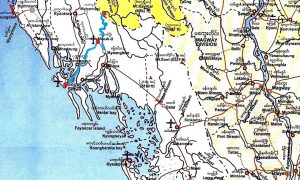

For many years under Myanmar’s military rule, people from other parts of Myanmar could not enter Northern Rakhine State, just as most Rohingya could not leave. Thus among the Myanmar people to this day, the understanding of the Rohingya situation is not extensive. Any solution to the Rohingya problem must be a sustainable one in order to succeed.

The non-sustainability of the current situation is very apparent. Political pressures are felt by successive Myanmar governments because of the high population growth among the Rohingya, the effect of limited education/employment prospects on Rohingya well-being, and the lack of assimilation causing inter-communal tensions to spread quickly with unpredictable consequences. High demand for international assistance is generated every time a humanitarian incident occurs. This usually involves the same international donors, so there is also a real risk of “donor fatigue”.

Furthermore, the Rohingya in Northern Rakhine State are in effect, permanently stateless: lacking ID, protection, and having no guaranteed recourse to justice. As a result, illegal emigration into neighbouring countries and people trafficking are both possible and potentially encouraged; “slave labour” in cross-border economic activities is condoned and most international human rights conventions cannot be applied effectively, if at all.

Can the international community do more to help the Rohingya?

Neither Bangladesh nor Myanmar accept the Rohingya as citizens, who are said to be the largest single group of stateless people in the world. There is little sign of this changing any time soon. The Myanmar Government “segregation” approach continued by the SLORC/SPDC military regime (from 1964–2010) provided short-term stability and allowed the Rohingya to work while maintaining their essential seclusion. But this did not represent a long-term approach to the problem.

In the confusion of recent efforts to progress towards some solution of the Rohingya problem, one proposal was for “safe havens” in Myanmar and/or Bangladesh to allow Rohingya to move safely into Bangladesh. Not surprisingly, this was rejected by both countries for arousing an infringement on sovereignty. While such a zone might have allowed safe movement, it would have incalculable effect in terms of encouraging people to leave. Neither government wanted more people to move, or to add to the existing humanitarian risks. Such a zone might have brought a short term solution, but it would have inherent long-term disadvantages.

Current international cooperation in the area mainly involves humanitarian relief agencies—while this might have averted mass starvation, it does not underwrite the health and wellbeing of more than one million people. International mediation to produce a long-term, legally binding political solution is non-existent, but must be actively pursued. The UN Security Council is not likely to take up the Rohingya issue unless the situation deteriorates dramatically. No world leaders have taken up the Rohingya cause. There remains more to be done.

Some others have called for the United Nations to impose fresh sanctions against Myanmar because of the abuses against the Rohingya. It has been just a few years since the international community’s earlier sanctions against Myanmar were lifted (mostly in April 2012) in response to Myanmar’s free and fair by-elections, in which Daw Aung San Suu Kyi herself was elected. Two kinds of sanctions had been canvassed on this occasion: economic sanctions against Myanmar individuals believed to be indirectly responsible; and targeted sanctions against the Myanmar army.

There does not seem to have been any detailed discussions in New York about such sanctions, which may not have seriously interested permanent members of the UNSC. Sanctions against the Myanmar army could have been effective and could have been justified, but comprehensive economic sanctions would probably not have had any real effect and indeed could have harmed ordinary Myanmar citizens rather than anyone responsible. There would still be no guarantee that the offending Myanmar policies would change.

Can Australia do more to help the Rohingya?

From 1990s, Australia has provided substantial relief assistance through humanitarian agencies based in Myanmar, with full support of the Myanmar military regime. Australia also provided food aid through the WFP. Furthermore, Australia has been granting entry to Rohingya as refugees from 2005. Many of the “Burmese” entering Australia under the “humanitarian program” were Rohingya who were treated as asylum seekers/refugees and who now live, work, and study in Sydney, Melbourne, or Brisbane.

It has been reported that Australia is proposing to send back to Myanmar some (Rohingya) asylum seekers from Myanmar, who have been detained in the Manus and Nauru processing centres. Being stateless people, Australia must not attempt to “repatriate” the Rohingya or forcibly return them to Myanmar.

Australia should continue to provide humanitarian assistance directly to Myanmar to help the Rohingya, and should in principle accept them for resettlement in Australia. Furthermore, Australian Government should periodically report to the Australian people on the situation in Rakhine State.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

Trevor Wilson is a Visiting Fellow at the Department of Political & Social Change, Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, located at the Australian National University. He retired in August 2003 after more than 36 years as a member of the Australian foreign service, and after serving as Australian Ambassador to Myanmar (2000–03).

Header image: a Rohingya refugee couple in Kuala Lumpur, via Overseas Development Institute on Flickr, used under Creative Commons.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss