In this in-depth analysis, published in two parts this week, Lila Sari looks at vaccine distribution in Indonesia, and the surprising entrance of political parties into the roll-out.

Part 2: Party approaches

What role exactly do the political parties play in vaccine distribution? How do they access the vaccines, how do their approaches differ and what motivates them? I’ll be looking at these questions across two articles this week. In part 1, I examined the broader practices of vaccine acquisition and distribution by political parties and their partners. In Part 2, I look at how this plays out in Golkar, PDI-P and NasDEM’s approaches.

The Golkar Party

Media reports suggest that Golkar has received a large allocation of coronavirus vaccines from the government. Golkar was among the first to launch a party-led vaccination program, commencing on 21 March 2021. It has created a new a unit to run vaccinations and provide other pandemic-related services, which it calls “Yellow Clinics” (yellow is the colour of the party). Using these Yellow Clinics as its main facility, the party claims it had administered at least 200,000 doses of vaccines as of late August 2021. From the Yellow Clinic Instagram account, we can learn that the focus of distribution was Jakarta, with most of the mass vaccination events held at the central office of the party in Jakarta. Other regions in Java (West, Central, and East Java), Aceh, and South Kalimantan received the rest of the vaccines, but in much lower numbers. At the time of writing, the Yellow Clinic vaccination program continues, with the party now offering Pfizer vaccines for free in Jakarta.

Herd immunity/herding constituents: parpol and COVID-19 vaccines in Indonesia #1

Online and social media shows that several political parties are actively involved in the vaccination program.

Golkar’s ability to access the vaccines promptly and in large numbers was undoubtably a product of the party’s key role in the ruling coalition at the national level. Golkar general chairperson Airlangga Hartarto sits in the cabinet as the coordinating minister for economic affairs, a position which places him at the center of power and gives him the capacity to influence the Ministry of Health and other important agents in vaccine distribution, like PT Bio Farma.

Golkar is the quintessential elite party in Indonesia. It is dominated by wealthy and influential businesspeople, former bureaucrats, and former generals. These connections give it the organisational and financial capacity to convene and run many mass-vaccination programs. Between March and September, it seems Golkar thus primarily conducted its own vaccination campaign independently, though on a few occasions it collaborated with businesses and held mass vaccination events at factories, including at the PT Santos factory in Karawang, West Java, and a PT HM Sampoerna factory in East Java.

Golkar vaccination events, especially those in Jakarta, have also focused on promoting Airlangga Hartarto, the party chairperson, presumably reflecting his ambition to run in the presidential election in 2024.

A Golkar billboard in Jakarta. Photo by Yus Prinandy.

PDI-P

The core party in the ruling coalition, PDI-P has about a fifth of the seats in the national parliament, and President Joko Widodo is a party member. At the regional level, the party is also strong: in the 2018 local election, it won six of 17 provincial elections and 97 of 171 city/ district elections. PDI-P’s pattern of delivering mass vaccinations is different from Golkar. PDI-P is more diverse in terms of regional distribution, branding, and partnerships.

I have found media and social media reports of the party running mass vaccination events in many regions in Java, the southern part of Sumatra (Lampung, South Sumatra, Jambi), and Central Kalimantan. These are all areas where PDI-P is strong politically. The party still, however, focuses on Java more than other regions. Meanwhile, unlike Golkar events which often promote Airlangga, PDI-P mass vaccinations often do not place much emphasis on central party bosses, but rather highlight the role of local leaders who hold posts at the central and regional level. Some of them are national and regional parliament members, and also leaders of regional branches. For example, in Kendal Regency (Central Java), the mass vaccination promoted local figures such as head of the district branch, the provincial party leader, and the national parliament member from the region, Tuti Nusandari Rusdiono. The event also featured a local health official as a ‘’supervisor”.

Another example, a mass vaccination event in Bangka Belitung Province, put up a banner with five photos on it. They included the PDI-P’s crown princess and speaker of the DPR, Puan Maharani, a local member of the DPR, chairs of the provincial and district branches in the region, and the mayor. The mass vaccination itself was held at the so-called Rudi Center—an office that belongs to Rudianto Tjen, a DPR member and a prominent PDI-leader.

Mayor of Semarang City, Hendrar Prihadi and three Projo (pro-Jokowi) members in a mass vaccination on 16 September 2021 in Semarang (credit: Abdul Mughis).

Meanwhile, when it comes to collaboration, because PDI-P dominates the government at the central level and in many regions, the party can engage easily with local governments, and POLRI/TNI in holding these events. It can also readily use public facilities and resources, including community healthcare centers or Puskesmas, and local health offices (Dinkes) as well as local police or army resources, to provide both venues and personnel for their activities. In fact, according to one source in a government agency in Central Java, doctors from public healthcare facilities often complain about having to do extra work at these party-led vaccination events.

NasDem Party

NasDem is a new party that was founded by old oligarchs and political elites associated with Golkar and the Democrat Party. Similar to Golkar, it is an important part of the national governing coalition. Party leaders have tried hard to make themselves different from their predecessors, Golkar and the Democrat Party, and to create a new image to attract voters. Still far from being dominant in parliament and cabinet, the party has growing influence and power in some regions. In 2018, governor candidates supported by NasDem won elections in North Sumatra, West Java, Central Java, West Kalimantan, Southeast Sulawesi, and NTT. Furthermore, party chairperson, Surya Paloh is a media mogul who owns the MetroTV network.

Hence, it is not surprising that NasDem seems to have acquired quite a large quota of vaccines for its mass vaccination programs. Like PDI-P, the party relies upon, and foregrounds, politicians who sit in the DPR and in the provincial governments to lobby for access to vaccines. According to media reports I have compiled, NasDem has been dispensing more than 200,000 doses of vaccines, mostly in the greater Jakarta region but also elsewhere, including West Java, Central Java, Papua, NTT, and Bangka Belitung

Some of the politicians in charge of vaccine distribution happen to be related to local government heads, which presumably also makes it easier for them to acquire vaccines. Take the example of Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT Province) in eastern Indonesia. One DPR member from here, Julie Laiskodat, is the wife of the NTT Governor, Viktor Laiskodat. Both are NasDem elites and run businesses. As a DPR member and the governor’s wife, Julie could easily negotiate with the Ministry of Health to get a vaccine share for NTT Province. As the wife of the Governor, she leads various organisations responsible for women’s affairs (PKK, Bunda PAUD, etc.) in the province, which gives her an added incentive to get a vaccine quota and allocate it to her constituency. Unlike other politicians who hold only one-off or at most a few mass vaccination events, she is holding vaccination events in NTT regularly: twice a week from August, and scheduled to last until December.

Are party campaigns helping achieve herd immunity?

It is difficult to access reliable data on the number of doses allocated to parties, because these allocations take place through informal and non-transparent processes. Therefore, I tried to gather data from online media and social media, and compiled claims by party leaders about the number of vaccines parties were distributing. I identified eight political parties as being involved in vaccine distribution between March and September 2021. If each political party—based on public claims in the media—has distributed around 200,000 doses (a rough estimate), this will generate a total of around 1.6 million doses. This number is miniscule compared to the targeted population of 208 million and will contribute very little—less than 0.5 percent—to achieving the national vaccination coverage goal.

Sometimes parties and the leaders of the government’s COVID-19 taskforce suggest that these party-led vaccination programs help outreach in low coverage regions and among marginalised groups (e.g., transgendered persons and rubbish pickers), as informed by one Partai Solidaritas Indonesia member While it is hard to know about the latter claim, we can test the argument about regional coverage using information from parties’ social media and online media.

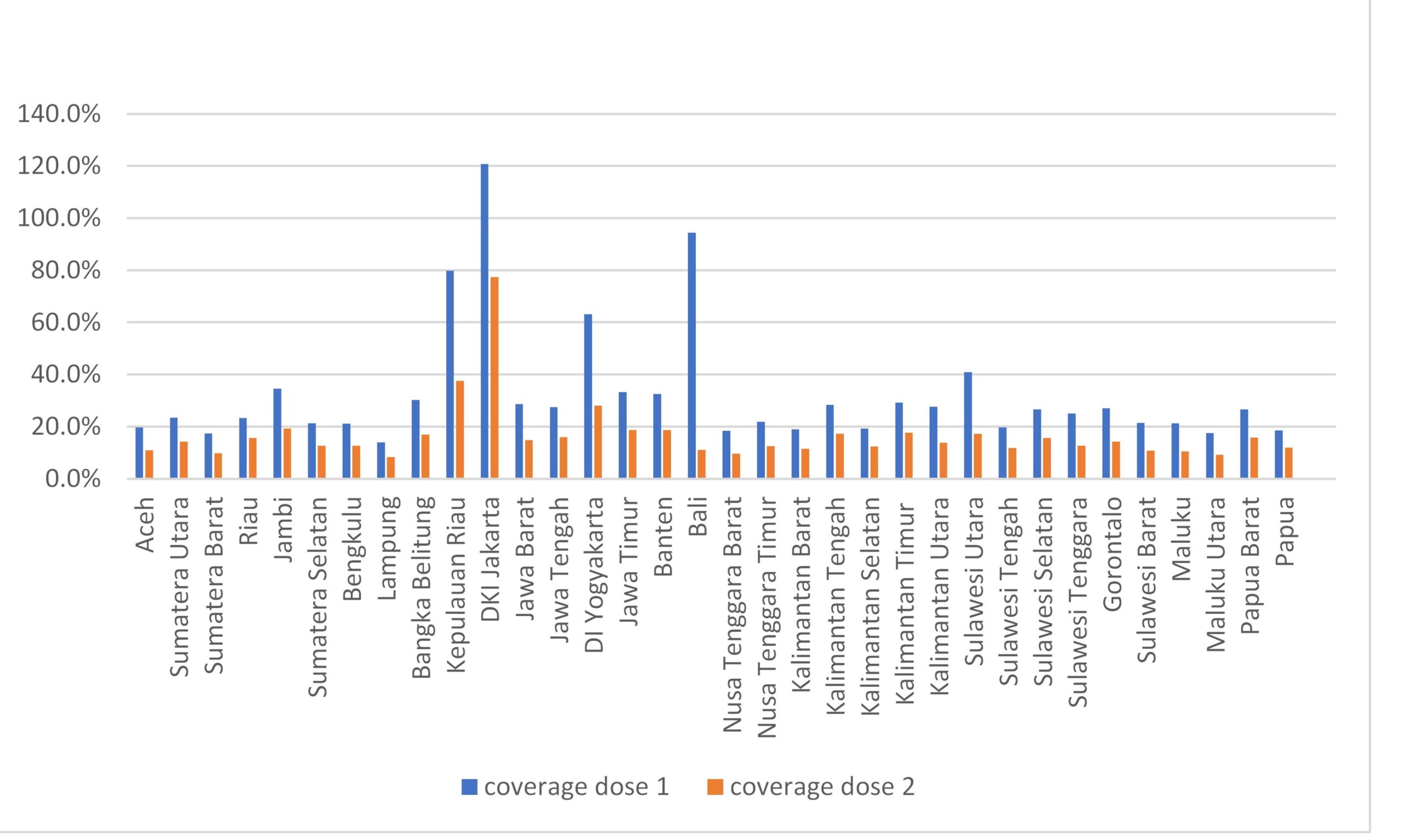

Before checking that information, we should see how the coverage rate of vaccinations varies across provinces in Indonesia (Figures 1 and 2). These figures use data from the Ministry of Health’s vaccination dashboard (SMILE) that are publicly available.

Figure 1. Graph of dose 1 and 2 vaccination rate in 34 provinces as of 6 September 2021. Source: https://vaksin.kemkes.go.id/#/vaccines

Figure 1 shows us that very few regions have achieved high vaccination rates (i.e., above 60%) for dose 1. The most successful provinces in this regard are DKI Jakarta, Bali, Riau Islands, and Yogyakarta. The ministry of health has prioritised these regions as centers of the economy, government, and tourism. Other provinces, however, are at or below 40% coverage rate. For second dose administration, Jakarta is the highest; Riau Islands, Bali and Yogyakarta are all still below 40% while other provinces are even further behind.

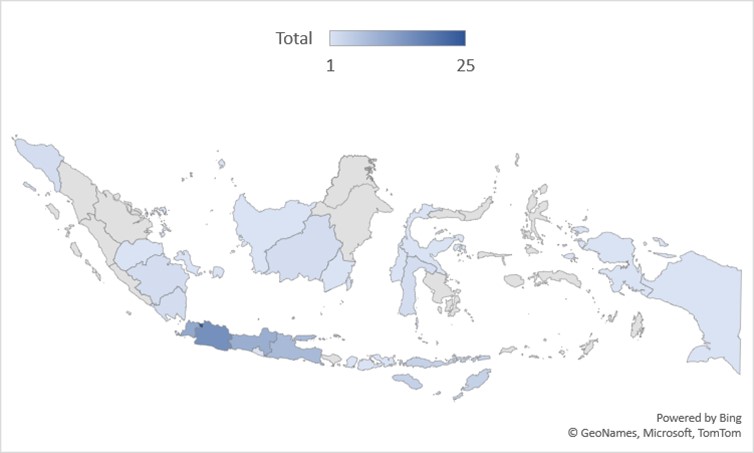

Now, where have political parties been holding their vaccination events? What regions did they focus on? Figure 2 shows the spatial variations of regions covered by political parties during the period of March to September 2021.These data are based on my own counts of events covered in the mass media and party social media accounts.

Figrue 2. Spatial variation of party-led vaccination programs. Source: various online media and social media.

Comparing the two figures, it is obvious that the parties are not distributing their vaccinations in places where coverage and capacity are low. Instead, they dispense vaccines in Java, particularly Jakarta and West Java, where the national vaccination roll out is working relatively effectively. The argument that party campaigns help to attain herd immunity and reach out to the areas where vaccines are most needed is weak.

Conclusion

What are we to make of these party-led vaccination programs? The examples presented above imply that the parties are using these programs to promote the popularity of party leaders and cadres. The parties do so by crafting an image that they are being responsive and helpful to the government, whilst also sending out a message that they have fought hard to get an allocation from the government to their people.

These events are heavily political—but political in the distinctive clientelistic sense that is the dominant mode of politics in Indonesia. The newly democratized political system has generated intense competition among parties and politicians. It also makes winning elections expensive. The political parties and their leaders need to always be finding new ways—even during this global pandemic—to keep their supporters loyal and win over new voters. The fact that is often incumbent DPR members who organise these events in their own electoral districts shows that the parties are using these events to provide favors—potentially lifesaving favors—to their political supporters in their own base areas. Distributing vaccines is thus an excellent way to supplement the old-fashioned forms of patronage distribution, such as handouts of money, food, government jobs and contracts, which are typically more costly—politicians often have to provide these themselves – and have less impact.

While the benefits to the parties and their politicians are clear, whether these events really help the national vaccine roll out is less so. The party-led vaccination programs surely target and prioritise their own constituents and supporters, meaning that those with the right political connections have the privilege of getting vaccinated before those who lack such connections. This can disrupt the targeting of those who need vaccines the most.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss