I first encountered Habib Bahar bin Smith at a demonstration near the Myanmar embassy in Jakarta in September 2017. From a distance, I noticed a group of young men wearing black military-like uniforms, pushing through the crowd in a VIP protection formation. The first thing I noticed about the particular VIP amid them was his pale skin and the blonde hair that fell over his shoulders—as if he was cosplaying as a pre-dreadlocks Axl Rose, but with a peci instead of a bandana. He was wearing a pair of designer aviator sunglasses and a full-length beige trench coat under Jakarta’s midday sun. Surrounded by his team of bodyguards, he walked with the swagger of an A-list celebrity towards the Myanmar embassy, where a crowd had gathered to protest the persecution of the Rohingya. The only thing more striking than Habib Bahar’s fashion sense was the enthusiasm for him from the sun-baked crowd. The demonstrators were literally throwing themselves at him. “Bib! Bib! Bib!” they called out affectionately, with hands stretched out—as far as the bodyguards permitted—in an attempt to touch him.

Habib Bahar swarmed at a demonstration at the Myanmar embassy, Jakarta (Photo from Habib Bahar’s since-deleted Instagram account)

After being helped by his followers onto a mobil komando (a pickup truck with a built-in stage and a sound system), Habib Bahar delivered a furious speech to the spellbound crowd, calling on the demonstrators to slaughter their Burmese enemies. The crowd went wild as he threatened to storm into the embassy, and chanted with Habib Bahar until he was escorted down from the mobil komando to depart with his convoy.

I was left wondering about his identity, and what made him so appealing to his devotees. At this stage, Habib Bahar was an obscure figure; a rudimentary internet search I made after the embassy protest yielded little information about this Jakarta-based Islamic preacher. Yet at the time of writing in late 2018, Habib Bahar is one of the most talked-about Islamic figures in Indonesia, the stuff of news headlines and social media notoriety. The story of who he is and how he got from the margins to centre stage reveals much about the dynamics of the Islamic preaching (dakwah) market in contemporary Indonesia, the increasingly ambiguous distinction between celebrity and religious authority, and the opportunities for fame and influence that are now available even to fringe figures if they become targets of law enforcement under the Jokowi government.

Prophetic lineage

Habib Bahar bin Smith was born in Manado in 1985. He is affectionally known as Habib Smith and Habib Bule (bule is a colloquial term used to describe white foreigners) because of his pale skin, sharp facial features and blonde hair. Habib Bahar is a sayyid, or a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad. His lineage can be traced to his great grandfather Habib Alwi bin Abdurrahman bin Smith, who was the first from his father’s side of the family to be born in Indonesia after leaving the Hadhramaut region of modern-day Yemen. Thanks to this lineage to the Prophet Muhammad, he is addressed with the honorific title exclusively for the sayyids, “Habib.”

Habib Bahar’s admirers praising his “good looks” on his facebook page

His ancestry partly explains his appeal and why the demonstrators were trying to touch him. According to Syamsul Rijal, who has done extensive research on followers of habaib (the plural of habib) in Jakarta, this is especially common amongst the followers of habaib as many believe that “touching a habib’s hands and robes allows transmission of blessings from the Prophet to them”, in a practice known as tabarruk.

Habib Bahar certainly makes a good use of this prophetic lineage in the increasingly competitive dakwah market in Indonesia. He preaches unquestioning respect for the descendants of the Prophet and for ulama (a ethos common among traditionalist Muslims), and refers to himself as someone with darah suci, or holy blood. His humble traditionalist Islamic boarding school (pondok pesantren salafiyah) on the outskirts of Jakarta is called Tajul Alawiyyin, which evokes his claimed Alawiyyin family lineage. Even the name of Habib Bahar’s own civil society organisation, the Prophet Defenders Council (Majelis Pembela Rasulullah), touts his bloodline.

Man wearing a hoodie from Habib Bahar’s Prophet Defenders Council at a demonstration. The merchandise of his Prophet Defenders Council is now increasingly common at events which typically attract habaib followers (Photo by Author)

Habib Bahar also draws from informal networks of habaib and Indonesian Arabs with a lineage to Hadhramaut for his dakwah opportunities. When he was 24, he married Fadlun Faisal Balghoits, another descendent of the Prophet. He has close ties with the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) leader Habib Rizieq Shihab, after whom Habib Bahar named one of his four children. Habib Bahar also keeps a personal relationship with Habib Rizieq’s son-in-law, Habib Muhammad Hanif Alatas, who often appears side-by-side with him at preaching events and demonstrations.

An everyday man’s holy man

Habib Bahar presents himself as an ordinary person’s holy man. In his sermons, he frequently speaks on behalf of the ordinary people (rakyat) against elites (which include Jokowi’s government, his political patrons, and Chinese Indonesian tycoons). Despite his exalted lineage, Habib Bahar seems to go out of his way to not conform to the stereotype of a saint-like Habib. He is known for his use of coarse language, even in sermons. Shouting loudly with his chain-smoker’s voice has become the trademark of his preaching style.

To the extent that he was famous outside of this religious base, Habib Bahar was known for leading his followers to raid what he called places of immorality (tempat maksiat) in the name of the Qur’anic edict amar ma’ruf nahi munkar, or “promotion of good and prevention of vice”. The first time Habib Bahar captured the attention of the mainstream media was when he raided a café in Jakarta’s suburbs for selling alcoholic drinks during Ramadhan.

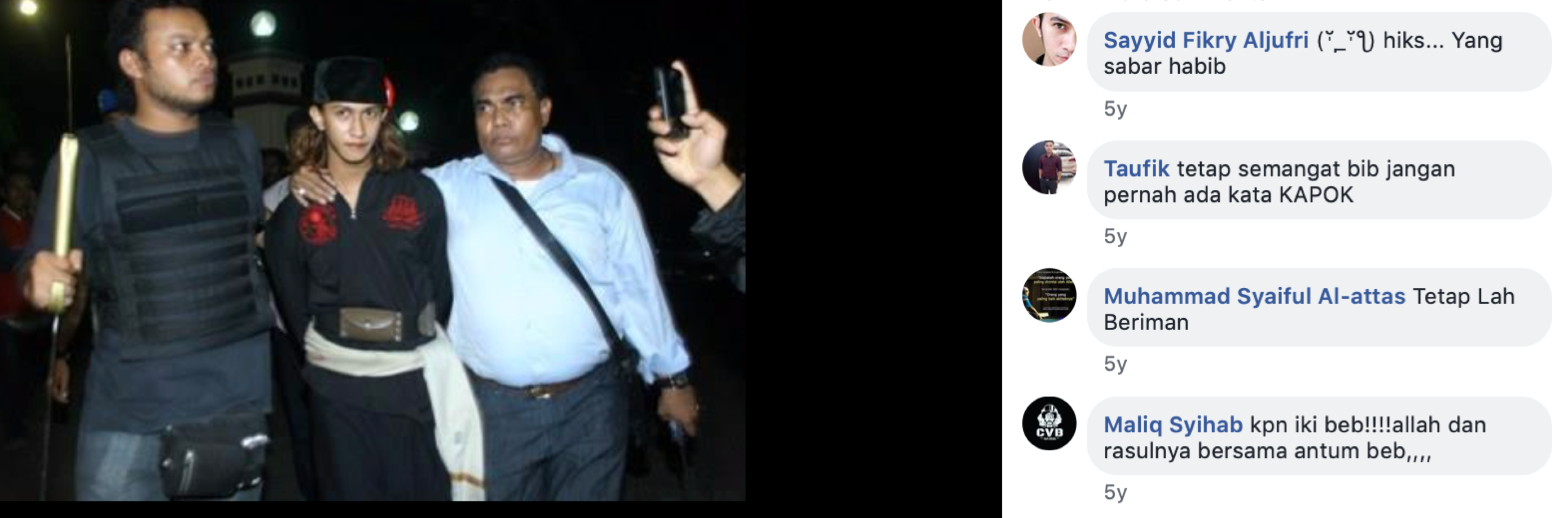

Given their fondness for samurai swords, it was not surprising that he and his mostly underage followers were found carrying the weapons when they were arrested by the police. This incident gave Habib Bahar a reputation as a preman (a colloquial term for street thugs and gangsters). But instead of seeing his criminal record as detrimental, Habib Bahar even used the image of his arrest as his social media profile picture in 2013, presumably to strengthen his street cred.

Habib Bahar’s 2013 arrest photo on his Facebook page

While many would understandably see him as a violent religious thug, in other quarters the preman image is just part of Habib Bahar’s appeal as a “successful” ordinary person who defends the interests of those from the same humble class background that he claims. Habib Bahar has sought to live the most ostentatious lifestyle his dakwah activities allow him to. In addition to his attention-grabbing fashion sense, he drives around in flashy cars with personalised registration plates and jets across the archipelago for dakwah. While this sets him apart from the rest of the rakyat, Habib Bahar’s lifestyle—presumably limited by his comparatively modest wealth rather than by choice—does not elevate him to the fantastical heights of lifestyle associated with Indonesia’s mainstream elites.

“Thank God we could take photo together with Habib Bahar’s car.” It’s worth pointing out that the car in the photo is a Mazda MX5, but Habib Bahar replaced the logo to Italian supercar brand Maserati.

Similar to the FPI headquarters in Petamburan, his small Islamic boarding school remains sparsely furnished, judging from images available online. Apart from a new main hall, most of the school was built using gedek bambu (a woven bamboo panel) and atap nipah, or rooftop made of dried leaves of nipa palms. To help improve the quality of his humble boarding school, Habib Bahar even requested his followers to contribute building materials like bags of cement. It would seem that Habib Bahar prioritises enlarging his automobile collection over upgrading the infrastructure of the boarding school that advertises his proud lineage to the Prophet.

Habib Bahar with his gold Toyota Crown, taken from his Facebook page.

In contrast to his firebrand public persona, Habib Bahar is known as an accessible and good-humoured person to his family and friends. He maintains a close relationship with his pesantren students and will often post social media videos of himself iseng together with them. (Iseng is an informal Indonesian term which can be roughly understood as engaging in mildly mischievous behaviours out of boredom.) Typical of this genre are the videos of Habib Bahar smashing tiles on his students’ heads or hitting students’ stomach with a samurai sword in the name of ilmu kebal, an Islamic-infused martial art of invulnerability.

Aksi Bela Islam fame

Until 2017, Habib Bahar was virtually unknown beyond his limited circle of students and admirers. But thanks to the Aksi Bela Islam protests that began in 2016, Habib Bahar was able to reach a level of fame he probably didn’t imagine was possible. Like many others in search of larger audiences, Habib Bahar has been an active participant in the anti-Ahok rallies and their spin-off events. Habib Bahar would make grandiose appearances at demonstrations, leading his flag-bearing followers, delivering provocative speeches, and occasionally engaging in physical provocation with the police. In doing so, he was able to build up a reputation as a fire-breathing holy man who dared to challenge the authorities.

But Habib Bahar actually owes much of his sudden fame to critics of the Aksi Bela Islam. His abrasiveness and his “lower-class” language and aesthetic make him a popular target on social media. Memes and videos mocking him went viral on Facebook and Instagram, inadvertently giving him a boost in publicity and occasionally offering him the opportunity to further enhance his street cred as a defender of the rakyat and Islam.

A vendor selling Habib Bahar’s portraits in Purwokerto, Central Java, next to the portrait of NU’s founder Kiai Hasyim Asy’ari. Partly thanks to the Aksi Bela Islam, his fame has spread beyond Jakarta. Author photo

This dynamic was seen in a conflict Habib Bahar had with Instagram in November 2018. Some of the social media site’s users orchestrated a campaign to take his account offline by repeatedly reporting his Instagram posts for violations of the site’s terms of service, which resulted in the suspension of his account. A furious Habib Bahar mobilised his followers and allies from the FPI to Instagram’s office in Jakarta. Accompanied by Habib Rizieq’s son-in-law Habib Hanif, Habib Bahar demanded that Instagram and its parent company Facebook stop carrying out what he alleged to be the government’s efforts to silence ulama and habaib. In the end, Habib Bahar received a widely publicised apology from Instagram’s representatives and scored a major victory in the eyes of his supporters.

Habib Bahar’s detractors continue to scrutinise videos and images related to him and, in their outrage, inadvertently make what they see as offensive content go viral. In the last couple of months, Indonesian netizens were treated to a viral video Habib Bahar’s making bizarre statements about women’s faces and genitalia, a video of him driving (on public road) with one foot on the steering wheel and the other on the throttle, and most notoriously, a video of him calling Jokowi a banci, a derogatory word for transgender. After his banci remark, Habib Bahar was reported to the police by Jokowi supporters for insulting the president. Whether or not they discredited him, Habib Babar’s detractors had undoubtedly given him his first truly nationwide media profile through this criminal case.

Unsurprisingly, Habib Bahar then took the opportunity to further strengthen his street cred. He first rejected the police’s summons for an interview, claiming that he was busy teaching his students. When he was eventually interviewed by police, he was escorted by an entourage of supporters to the station; they demonstrated outside while he was interviewed.

Aksi 121 (12 January 2018) protestors demonstrating in front of Facebook’s Jakarta offices. They demanded Facebook stop blocking the accounts of their ulama. Author photo

His criminal case also earned Habib Bahar an extended interview with national television station tvOne, and the opportunity to “debate” with a presidential palace official, Ali Mochtar Ngabalin, on live television. (The video of their exchange has accumulated nearly 8 million views on YouTube.)

But the biggest windfall from his legal case was being given the opportunity to deliver a speech on the main stage at the second reunion of the Aksi Bela Islam 212 on 2 December 2018. Speaking in front of a crowd of hundreds of thousands of people, he vented his spleen at Jokowi’s supposed instructions to use tear gas against the habaib, kiai, and ulama who demanded to meet the president at the Aksi 411 in November 2016. (There is no evidence that Jokowi issued any such instruction.) He justified calling the president a banci for refusing to meet the Islamic leaders. “I’d rather choose to rot in jail than having to apologise to Jokowi,” he declared.

Habib Bahar as an anti-Jokowi martyr?

Within a relatively short period, Habib Bahar has, by chance as much as design, followed in the footsteps of Habib Rizieq Shihab in moving from the margins of Islamic life to take the centre stage in an anti-Jokowi movement. Certainly, the attention Habib Bahar has been getting shouldn’t be mistaken as widespread public support. His idiosyncrasies, his vulgarity, and his preman-like public persona may be popular among his devotees, but surely limit his appeal even to more mainstream Aksi Bela sympathisers, who blame people like him for giving the movement a bad name.

Piety, politics, and the popularity of Felix Siauw

An ethnic Chinese convert to hardline Islam stands out in Indonesia’s crowded Islamic preaching market.

To those who seek to dethrone Jokowi in 2019, Habib Bahar’s legal predicament makes him a useful victim. Following FPI’s leader-in-exile Habib Rizieq’s legal trouble, another descendent of the Prophet becoming “criminalised” by the government is exactly the sort of story Jokowi’s rivals need to stoke the fading “criminalisation of ulama” narrative. Gerindra’s Fadli Zon has already described Jokowi’s handling of the Habib Bahar case as “total oppression”.

Unfortunately for these political players, Habib Bahar might be testing the limits of his status as an anti-Jokowi martyr. At the time of writing, Habib Bahar had just been detained by West Java police for allegedly kidnapping and torturing two young men, one of them a minor, at his pesantren as punishment for impersonating him in Bali. A video of Habib Bahar violently assaulting one of the alleged impersonators in front of his students has gone viral on social media following his detention. For the moment, it seems that Habib Bahar might be granted his wish to become the martyr who “rots in jail.”

Screen capture of the viral video of Habib Bahar allegedly assaulting a minor

It may be tempting to dismiss Habib Bahar and his devotees as extremist outliers. But one could have said the same things about the FPI in 2008, when it disgraced itself in mainstream eyes by attacking minority rights activists at the national monument (Monas), further entrenching an image of FPI as preman berjubah (“thugs in [Islamic] robes”). Yet there is growing acknowledgement that FPI has achieved a level of legitimacy as a mobilisational force for Islamist grievances, thanks to the important role it played in the anti-Ahok campaigns, and its continuing role in the “212” protests movement. In addition to the platform offered by the 212 movement, the mainstreaming of Islamist outliers has also been aided by their becoming targets of what they have portrayed as persecution through “criminalisation” at the hands of the Jokowi government. Habib Bahar is arguably one of the most surprising, yet vivid, illustrations of this dynamic so far.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss