The late Singaporean novelist Gopal Baratham’s A Candle or the Sun, published in 1991, is rightly regarded as one of the finest works of literature to come out of the city-state (though probably not according to its government). Politically-minded, and not afraid to amble along a storyline of repression and state-enforced victimhood, it is small wonder Baratham’s writing was often compared to George Orwell’s. A Time magazine’s review of A Candle or the Sun states that it “picks up where George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four left off.” In the negative, both authors’ styles are admittedly a little too heavy with caricature and requisite pathos, especially when it comes to life’s victims. Indeed, A Candle or the Sun might initially catch one’s eye as a Southeast Asian transmutation of Nineteen Eighty-Four. As Baratham would say in an interview, he wanted to complete the book by 1984 “for Orwell” but couldn’t finish it until the end of 1985. The book is set in 1983. It took another six years to find a publisher, which was Serpent’s Tail, of London.

A more discernible reader, however, might also notice the traces of Keep the Aspidistra Flying. A bored salesman and failing amateur writer (a la Gordon Comstock), Baratham’s protagonist, Hernie Perera, gives up on his artistic dreams, though with the promise of literary success, when he accepts a job offer from an old friend to work at the Ministry of Culture producing propaganda. Both Comstock and Perera are susceptible to hypocrisy gilded in justification, mistreatment of their lovers for their own advancement, and an overestimation of their own literary merits.

A more discernible reader, however, might also notice the traces of Keep the Aspidistra Flying. A bored salesman and failing amateur writer (a la Gordon Comstock), Baratham’s protagonist, Hernie Perera, gives up on his artistic dreams, though with the promise of literary success, when he accepts a job offer from an old friend to work at the Ministry of Culture producing propaganda. Both Comstock and Perera are susceptible to hypocrisy gilded in justification, mistreatment of their lovers for their own advancement, and an overestimation of their own literary merits.

Perera’s self-respect is lost (though later redeemed) when he betrays to his new employers his lover Su-May, a member of anti-government Christian sect that is printing a “street paper.” This oppressive state is ominously distant from the story, however. (The setting is clearly Singapore, despite the book’s forewarning that “any similarity of persons, places or events depicted herein to actual persons places or events is purely coincidental.”) Perera does muse on how the state wants a say in even the most minute points of life (“your masters kennel you in neat boxes, doctor your females, control litter size according to pedigree and tell you what names you can give your pups,” to give one example.) And Perera is later chided by the lover of his friend: “Did they never tell you that on this island of paradise of ours trade is a matter of security, education is a matter of security, health is a matter of security, how you wash your underwear is a matter of security.”

The Singaporean academic Ban Kah Choon apparently once described him as a “magician who stands before the unknown to decipher what has yet to be written.” Ignore the pretentiousness and incoherence of this statement; Baratham, after all, was fictionalising fact in A Candle or the Sun: specifically, Operation Spectrum, the Singaporean government’s attempt at McCarthyism. But he was certainly charting a new course in Singaporean literature. And instigators often have to be more obvious. Baratham was at his best when he was at his subtlest, though he often had the habit of repeating his understatements so often they become glaring. Indeed, re-reading A Candle or the Sun in light of the more recent politically-natured novels from Singapore (I’m thinking in particular of Jeremy Tiang’s understated State of Emergency, published in May) one gets the sense that Baratham subscribes to the hammer-to-crack-a-nut cliché.

Three years after A Candle or the Sun was published, Catherine Lim, another Singaporean writer, earned a rebuke from Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong for her articles in the Straits Times. Writers on the fringe must not challenge the government, the Prime Minister said. There were suspicions, during the ‘90s, of Baratham being the city-state’s “token liberal,” an author who avoided the sort of criticism and censorship others faced. “You should criticize the faults if you care for the society,” he said in 1996. “Some people say I’m the government’s token liberal. What can I say?”

His background, perhaps, afforded him some protection. Born in 1935, decades before Singapore became an independent nation, he followed his parents’ footsteps into the medical profession. At 36, he finally graduated from the University of Edinburgh, specialising in neurosurgery, after training at the Royal London Hospital. He would later return to Singapore, eventually becoming the head of Tan Tock Seng Hospital’s neurosurgery department. In 1991, the same year A Candle or the Sun was published, he was elected president of the ASEAN Association of Neurosurgeons.

His prominence in the medical field, at least in Southeast Asia, was not quite equalled by his literary recognition. A Candle or the Sun became his first published novel, after two collections of short stories, and won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize in 1992, which he reportedly turned down because, he said, it was awarded based on the panel looking for a “Singapore style of writing” when he considered his work international (most of his work was published by British publishing house, not Singaporean ones). He attempted another novel and a non-fiction book after A Candle or the Sun but it was that work that kept his name in alive among the talking classes.

His death, in 2002, gave chance for his reappraisal as an interlocutor for free speech in Singapore. Teng Qian Xi, writing in the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore at the time, offered a retrospective: “The criticism of the Singaporean ethos of conformity and rationality, as well as the questioning of memory, rhetoric and history which I often found forced in his stories became more exciting, less pedagogical in A Candle or the Sun.”

Freedom from speech

I do not know how widely A Candle or the Sun is still read in Singapore. I am told anecdotally that, like Nineteen Eighty-Four is around the world, it’s known by many but read by few. I hope not. Nonetheless, it remains an easy-to-hand reference for free speech matters. Indeed, how little things seem to have changed since it was published. The People’s Action Party (PAP) is still in power, as it has been since Singapore gained its statehood. The country’s media remains closed. MediaCorp dominates television and radio, and is the only terrestrial TV broadcaster. It happens to be controlled by the government-owned investment arm, Temasek Holdings, the CEO of which is Ho Ching, the wife of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. As for the newspapers, the Straits Times is owned by Singapore Press Holdings. Its current CEO is Alan Chan, who previously served in several government positions, and its chairman Lee Boon Yang, who served as an MP for the ruling party from 1984 until 2011, and held Cabinet positions during that time.

When Baratham was interviewed after the publication of A Candle or the Sun, he laconically defended himself: “It’s not that I want to irritate, but I just speak my mind… You should criticize the faults if you care for the society.” But this is a concept that still doesn’t find ear among the ruling elite, despite its rhetoric. In February, the Prime Minister commented: “If all you have are people who say, ‘Three bags full, sir’, then soon you start to believe them, and that is disastrous.” On the same day, as the Economist pointed out, a respected former diplomat who now runs a public-policy institute at the National University of Singapore, said Singapore needs “more naysayers [who] attack and challenge every sacred cow.”

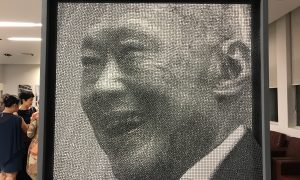

Singapore is now a 21st century economy propped up by 20th century politics. And the Sedition Act, on the books since the late 1940s, is still brought out to slap down those naysayers, especially those who criticise the sacred cows, namely religion and race. PM Lee Hsien Loong has defended Singapore’s limits on free expression as a means to safeguard social stability. “In our society, which is multiracial and multi-religious, giving offence to another religious or ethnic group, race, language or religion, is always a very serious matter,” he said. This has been the case since Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding Prime Minister (and the current PM’s father), promised in 1965 to build a multiracial nation. “This is not a Malay nation; this is not a Chinese nation; this is not an Indian nation. Everyone will have his place, equal: language, culture, religion,” he commented that year.

Today, Indeed, Singapore is a multiracial state. And a heavy dose of state-enforcement has gone into defending this idea. Singapore celebrates Racial Harmony Day—July 21, the day when the riots broke out in 1964—and schoolchildren are taught about religion and ethnicity. But the idea that by suppressing “hate-speech” one can improve society reveals hidden impulses behind those who call from restraints. It is, at the same time, utopian and nihilistic.

I’ll take a fairly positive-slanted story from the Straits Times, dated November 8, 2015, as an example. The article’s author describes Singapore as a microcosm, “which pledges to be color-blind in its meritocracy and economic growth by providing opportunities for all”. From these, and numerous other reports, one gets the sense that perhaps the government is justified in trying to silence what it considers hate speech.

But a number of commentators are quoted as saying that Singapore is “nowhere near being a race-blind society” because racist undertones are hidden under the surface of a seemingly cohesive society. They also said that “some people and groups are downright ignorant and biased, others merely tolerate, but others are proactive in understanding and being appreciative”. One sociologist opined that “bubbling beneath our civil veneer, there are prejudices and stereotypes which occasionally surface to trigger bouts of soul-searching”. Indeed, the death of a foreign worker in Little India in 2013 led to a riot of more than 300 people, during which 54 officers and eight civilians were injured.

But silencing any public discourse on race or religion doesn’t seem to have done much good (just as banning mention of food isn’t a cure for malnutrition). As seen over the decades, while tensions remain dormant most of the time, they do have the recurrent habit of bubbling up. Moreover, not talking about the issue doesn’t always mean it will go away. A 2013 survey found that almost half of Singaporeans didn’t have a close friend of another race.

At some point in A Candle or the Sun, Perera is warned: “culture is a matter of security.” So, too, is culture a matter of free speech. While “hate-speech” does exist, all too often free speech is curtailed in Singapore over claims that individuals have offended a religion or race, when what they have really done is criticise the government. A casual glance over the cases of people recently prosecuted for free speech reveals that courts tend to find some facet of religious or racial offence in the person’s comments.

Take the case of the blogger Amos Yee, who was prosecuted twice for wounding religious feeling, not for criticising the government. As Singapore’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, Foo Chi Hsia, said in 2015, “Amos Yee was convicted for insulting the faith of Christians…Protection from hate speech is also a basic human right.” Indeed, from this comment one can denote the legal contortionism of the Singaporean government: its citizens have the right of freedom from speech, which, to the government, is more important than freedom of speech. Yee might have gone on a tirade against religion, but his main target for criticism was the government, specifically the death of Lee Kuan Yew, in 2015. He called the late leader “a horrible person”, an “awful leader” and a “dictator,” as the Economist reported. Indeed, the American government was clearly of opinion that Yee was persecuted for his political views when it offered him asylum this year. “This is the modus operandi for the Singapore regime – critics of the government are silenced by civil suit for defamation or criminal prosecutions,” one American immigration judge wrote during Yee’s asylum ruling. To which the Singaporean government responded that America allows “hate speech under the rubric of freedom of speech.”

It is often too easy to defend the freedom of speech for the likes of Baratham, a learned doctor and adroit novelist. Harder, though, to defend the uncouth ramblings of someone like Yee. As I wrote in the Diplomat at the time: “It is clear that most of [Yee’s] comments were crude and inarticulate and, befitting his age, childish. This doesn’t mean, however, he ought not be defended for merely uttering an opinion.”

Taking the candle

George Orwell once described Speakers Corner, in London’s Hyde Park, as “one of the minor wonders of the world.” On my last visit to Singapore, last year, a reposeful afternoon provided me with a moment to visit the city-state’s own attempt at a Speakers Corner, located in Hong Lim Park. Oh, how imitations are inferior. The Economist described it thusly:

[A] spot set up for Singaporeans to exercise their freedom of speech without any restriction whatsoever, beyond the obligation to apply for permission to speak and to comply with the 13 pages of terms and conditions upon which such permissions are predicated, as well as all the relevant laws and constitutional clauses.

That article was about the prosecution of blogger Han Hui Hui who, in 2014, journeyed to Speakers’ Corner to protest the management of the Central Provident Fund, the city-states compulsory social security fund. She was found guilty and fined more than $2,000 last year not for voicing her opinion, a government spokesperson said, but for “loutishly barging into a performance by a group of special-education-needs children, frightening them and denying them the right to be heard.”

But what’s surprising about Speakers’ Corner is that Singapore would even attempt a parody. But, then again, Baratham understood the importance of the masquerade. The real heft of A Candle or the Sun is not in how an oppressive state operates but how people are so ready to sacrifice (and justify sacrificing) freedom for “good housing, safe streets, schools for your children and… three square meals a day and a colour TV,” as Perera says. Indeed, principles are sacrificed with only the slightest enticement by the state, unlike in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

In 2013, a survey of 4,000 Singaporeans asked whether they preferred “limits on freedom of expression to prevent social tensions” or “complete freedom of expression even at risk of social tensions.” 40% of respondents went for limits and 37% said complete freedom. The remaining 23 percent had no opinion on the matter, which perhaps says something about public participation in Singaporean society.

If Nineteen Eighty-Four is a novel that represents what Orwell described as “the dirty-handkerchief side of life” then Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, published 17 years earlier, is its saccharine facsimile. Huxley in a letter to Orwell shortly after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four:

Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.

A Candle or the Sun serves somewhat as a synthesis between the censorial warning of both dystopias. Baratham understood that too much jack-booting, never the first port of call for the Singaporean repressors anyway, couldn’t last. (A Candle or the Sun happened to be published the year the Soviet Union collapsed). Equally, permissiveness, unlike in Brave New World, had to be carefully managed: provide a glimpse but never the real thing. Perera, an intelligent man, understands the cognitive dissonance one needs to survive in such a world. A noted passage in A Candle or the Sun finds him musing over whether to take the censorial job. He compares his position to that of a prostitute. “Once I’ve accepted Sam’s job,” he thinks, “I was sure I would have to do things distasteful… I suppose this loss of self-respect is what distressed me. It must be something that all whores grappled with.” But as he soliloquises, he swiftly talks himself round to a justification:

The analogy with prostitutes was a good one. There must be prostitutes who are wives and mothers, who ran families, loved their husbands. Their salvation must lie in an ability to separate in their minds acts which were physically identical.

The psychically identical act, for Perera, was to be able to write artistically and censorially at the same time. In short, selling something that one doesn’t want to, nor believes in. Indeed, from his days running a furniture store, Perera reflects that salesmanship “consisted not of providing people with what they needed, but with that was essential to their dreams.” Shortly afterwards, he comments: “The possibility of winter is essential to the happiness of people living in the tropics.” Dreams, Perera realises, are all too willingly indulged and what people really need (freedom and autonomy) sacrificed. Indeed, do people want the candle (the intimation of freedom) or the sun (the real thing)? The government’s art of salesmanship, as Singapore’s history has shown, makes sure people readily opt for the candle.

• • • • • • • •

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss