Cambodia will vote on Sunday July 29. Today, the 20 competing parties can make their final appeals to the voters. It is the endpoint of a campaign that many have dramatically dismissed as a death knell for Cambodian democracy. Both publicly—through articles and social media posts—and in private conversations, people often draw on their observations and memories of Cambodia’s past elections to weigh in on the state of politics and to consider what options remain.

First, some background. National elections are held every five years. In 2013, the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), headed by Sam Rainsy and Kem Sokha, came close to defeating Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP). The results shocked the ruling party, which has effectively been in charge of the country’s affairs for almost four decades.

The ubiquitous CPP: campaign information at a restaurant (Photo: Katrin Travouillon)

After the commune elections in 2017 demonstrated that popular discontent with Cambodia’s longstanding leadership had not ceased, the government began a series of drastic measures. Sokha was accused of plotting a “colour revolution” with the help of the US and jailed on treason charges, for which he could face 14 years imprisonment. Rainsy left the country under threat of defamation charges. In November 2017, the Supreme Court dissolved the opposition party and barred its members from political activities for five years before redistributing their seats. The bulk of them went back to the ruling party, a handful were scattered among other “opposition” parties.

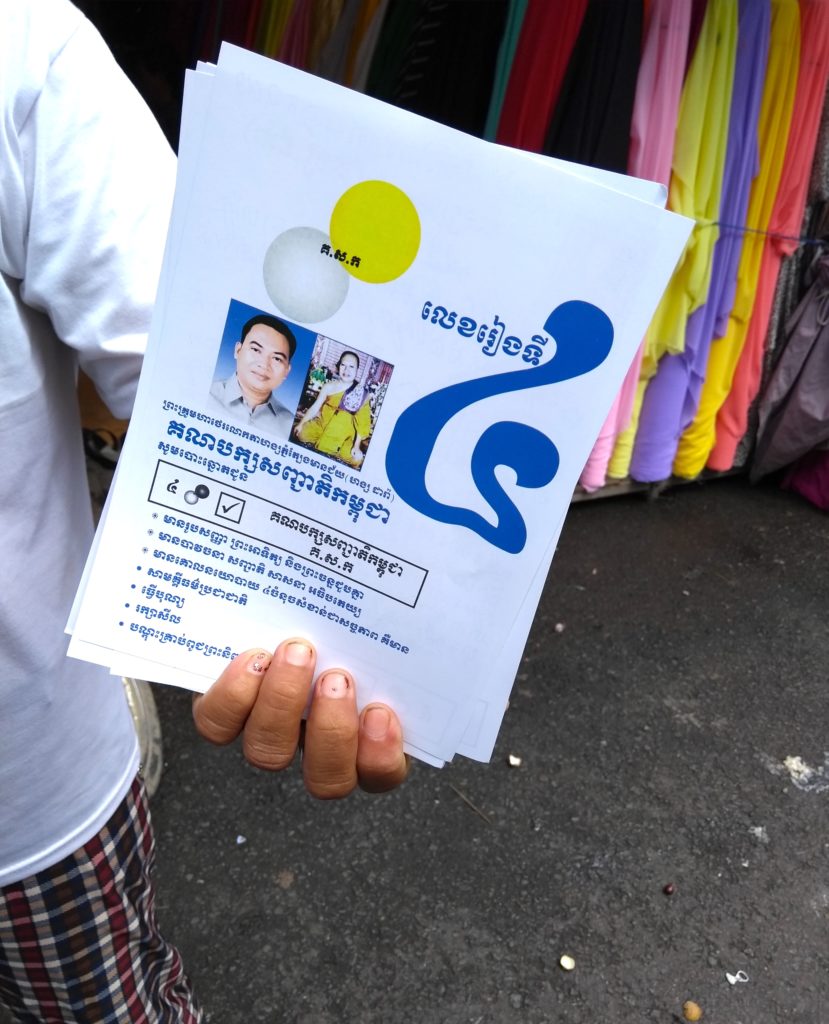

Opposition party materials (Photo: Katrin Travouillon)

So on Sunday, 19 parties will contest the CPP’s powerful grip. But without a major opposition party, this year’s election looks markedly different than previous ones.

The 2013 elections provide the most common backdrop to structure people’s observations of this year’s campaigns: compared to the bustling excitement and the loud and cheerful confidence displayed by CNRP voters all over the country, the opposition parties’ campaigns this year are mostly remarkable for what they are not. Even the capital Phnom Penh, otherwise the hub of campaign activities, is mostly silent and few things indicate that challengers to the CPP remain.

Yet for someone who has spent years combing through archives that document the work of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) it is the country’s first elections that still shape observations, at times producing an almost eerie sense of déjà vu:

what exactly is the role and agenda of the small parties? Will the government track voters’ choices in the ballot boxes? What will the total numbers of votes cast reveal about the future of Cambodia’s democracy?

These questions, now on the forefront of many voters’ minds, were just as intensely debated 25 years ago. At the end of its mission to implement the 1991 Paris Peace Agreements, UNTAC organised the country’s first democratic elections in 1993. The highly anticipated event was globally celebrated (some might say overly glorified) as the “birth of democracy” in Cambodia.

In 1993 as well as in 2018 a total of 20 parties registered to compete in the elections.

However, then, as now, the concept of a “political competition of ideas” was mostly elusive in an environment marked by fear and insecurity.

In 1993 it was the memories of the war that loomed large. During their televised campaign speeches Cambodian politicians alluded repeatedly to “mountains of bones, rivers of blood and an ocean of suffering” and appealed to their fellow politicians to prioritise national reconciliation. The theme was also evident in the parties’ names—Khmer Neutral Party or Liberal Reconciliation Party—and party symbols that used images like shaking hands or the peace dove.

Amidst the ongoing political violence in the country, the candidates chose their campaign locations and words carefully. “We live with the tiger and therefore must act in such a way as to avoid being eaten”, explained a candidate to an UNTAC official. Another observer noted in his report: “… the Bulletin of the Democratic Party is printed in a no-fuss black and white typescript. The Bulletin’s lackluster presentation style is carried over in content. This is no doubt a deliberate tactic to avoid direct criticism and the possibility of harassment.”

Distribution of opposition party leaflets at a market (Photo: Katrin Travouillon)

In 2018 similar tendencies can be observed. Many of the CPP’s competitors embrace the least objectionable of all causes in their campaigns and vaguely profess to “protect forests” or “end poverty” once in power. In his office, one party leader handed me a small program, the size of half a postcard, and gestured towards the breast pocket of his shirt: Easy to put it in here, he said. Easy to hide. And of course, small programs are also cheaper: most of the parties are notoriously under-financed and have only limited funding to spend on the campaigns. They focus their attention on going door to door in the provinces, talking to prospective voters and distributing their leaflets.

In the space of the city of Phnom Penh this translates into an overwhelming presence for the CPP. Huge, well-lit billboards have been erected at major intersections of the city. They line many of the large boulevards, streets and bridges. The party’s programs, slogans, and symbols have been glued to building walls at regular intervals. The portraits of the party’s leaders, Hun Sen and National Assembly president Heng Samrin, shoulder by shoulder, are omnipresent. There are tents, where party supporters alternately play campaign speeches and music. Expensive cars adorned with the CPP symbol can be spotted all over town. Shops sell CPP hats, shirts, phone cases and other merchandise. Rallies involve thousands of identically dressed supporters in cars, open trucks, and motorbikes and are flawlessly choreographed events: police are positioned on every corner, their ears pressed to their walky-talkies, waiting for their signal to stop the traffic and wave the motorcades through.

Heading to a CPP campaign rally, 22 July (Photo: Katrin Travouillon)

Amidst all of this, the campaigns of the other parties are difficult to find. None have a single billboard; their signs are small, mostly at the outskirts of the city, by the side of dusty roads. Some have taken to parking tuk-tuks decorated with flags and equipped with loudspeakers that blast recorded campaign speeches by their leaders towards the passers-by. Their processions have dramatically fewer supporters and the authorities are less likely to support their way through the city’s dense traffic, often leading to the campaign processions being cut into smaller and smaller groups of supporters.

Opposition banner in traffic (Photo: Katrin Travouillon)

In 1993, cognisant of the CPP’s relative wealth and reach even at that time, UNTAC tried to level the playing field by creating a radio station and then distributing radios in the provinces. One might assume that with the advent of social media and the intense popularity of Facebook in Cambodia the smaller parties could make up for much of the financial, material, and organisational limitations of their campaigns by reaching out to their supporters online. Yet, the government’s announcement to monitor social media ahead of the elections has spooked many and it is almost as quiet and monotonous on the web as it is in the streets of Phnom Penh.

Despite these restrictions and regardless of the media used, rumours travel fast in every era. To express their concerns and ask for advice in the run-up to the 1993 elections listeners from around the country wrote to the UNTAC radio station, which sometimes received several hundred letters a day. During a special program, selected letters would be read and answered on air. People had heard of magic pens or spy drones, and contacted UNTAC for advice.

Image shared on social media that promotes an election boycott

Similar stories circulate today. Smartphones and their integrated cameras make it unnecessary to imagine more elaborate methods of surveillance inside the ballot box, but the dominant themes of those rumours remain the same: people worry about the government’s ability to compromise the secrecy of the vote.

Which brings us to one last point: the current preoccupation with the total number of votes cast. During a televised statement in 1993, In Tam, the leader of the Democratic Party, urged his fellow people to go and vote to guarantee that Cambodia would no longer be isolated:

“Please participate in the elections; so that there are 90 percent or even more, so that they can see that we want to be a country that obeys the law and lives under the rule of law… Today they regard us as people living under the rule of the jungle, today there is nobody who recognises us; so if we do not all go to the elections, if we can’t be bothered to vote, then we will continue being a country that is excluded from the global community, so mobilise everything there is.”

And indeed, 90% did turn out, providing observers with the key element of their success story—despite the fact that both before and after the ballot it was business as usual and power-play and bargaining, not the will of the people, determined the end result.

Today, Sam Rainsy and his supporters urge the Cambodian people to stay at home to demonstrate that democracy can survive. Those who must go, they say, should spoil their ballots. They have dismissed all other parties as puppets or traitors and will claim every vote not cast for any party.

It is likely because of the tendency of the former CNRP members to bring up the Paris Peace Agreements, in their appeals from abroad, that people continue to regularly bring up UNTAC themselves: “they [UNTAC] installed the two prime ministers and then just left”, a shop owner said yesterday. A few days earlier she had also noted that “nobody will come to help because they already spent so much money then”.

A roadside concert as part of the CPP’s campaign (Photo: Katrin Travouillon)

Many commentators have loudly declared these elections “a farce”, “already over”, and “history” weeks before the polls have opened. And while it is true that Hun Sen is not going to disappear from the world stage by means of this vote, such statements are dismissive of those who are still grappling with the question of what the right decision under these difficult circumstances is.

To those people, who had neither the luxury to learn about the country’s history in libraries or archives, nor the convenience to observe and comment from the sidelines, it is the memory of another election that looms large: that of 1998 and the clashes leading up to it that turned Phnom Penh once again into a war zone.

Cambodia haunted by mistakes of interventions past

What we see today in Cambodia is a direct outcome of the events of 1997, and the world’s feeble response then.

Looking back, it becomes painfully obvious that not only are Cambodia’s elections flawed, they are also a flawed vehicle to trace political change in Cambodia. To those still committed to peaceful change, the simplistic tales of “birth” and “death” of democracy are meaningless. Cambodians will, as one party official said, just continue to use and engage whatever space remains. “It is important for us as Khmer, the leaders and the citizens, we must try ourselves, trust in ourselves and hope. We cannot give up. If we give up, if we think it is impossible, if we only think of losing, who is going to help us?”

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss