It is close to dusk when I navigate my way into Gillman Barracks, a fascinating pocket of Singapore where, to put it in an utterly romanticised way, artillery gave way to art. I head to the Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art (NTU CCA)’s exhibition space, where a friendly gallery sitter hands me the program booklet and a small torch.

“You will need it,” she states simply. I glance at the title of the exhibition – Ghosts and Spectres: Shadows of History – and decide that she is probably right.

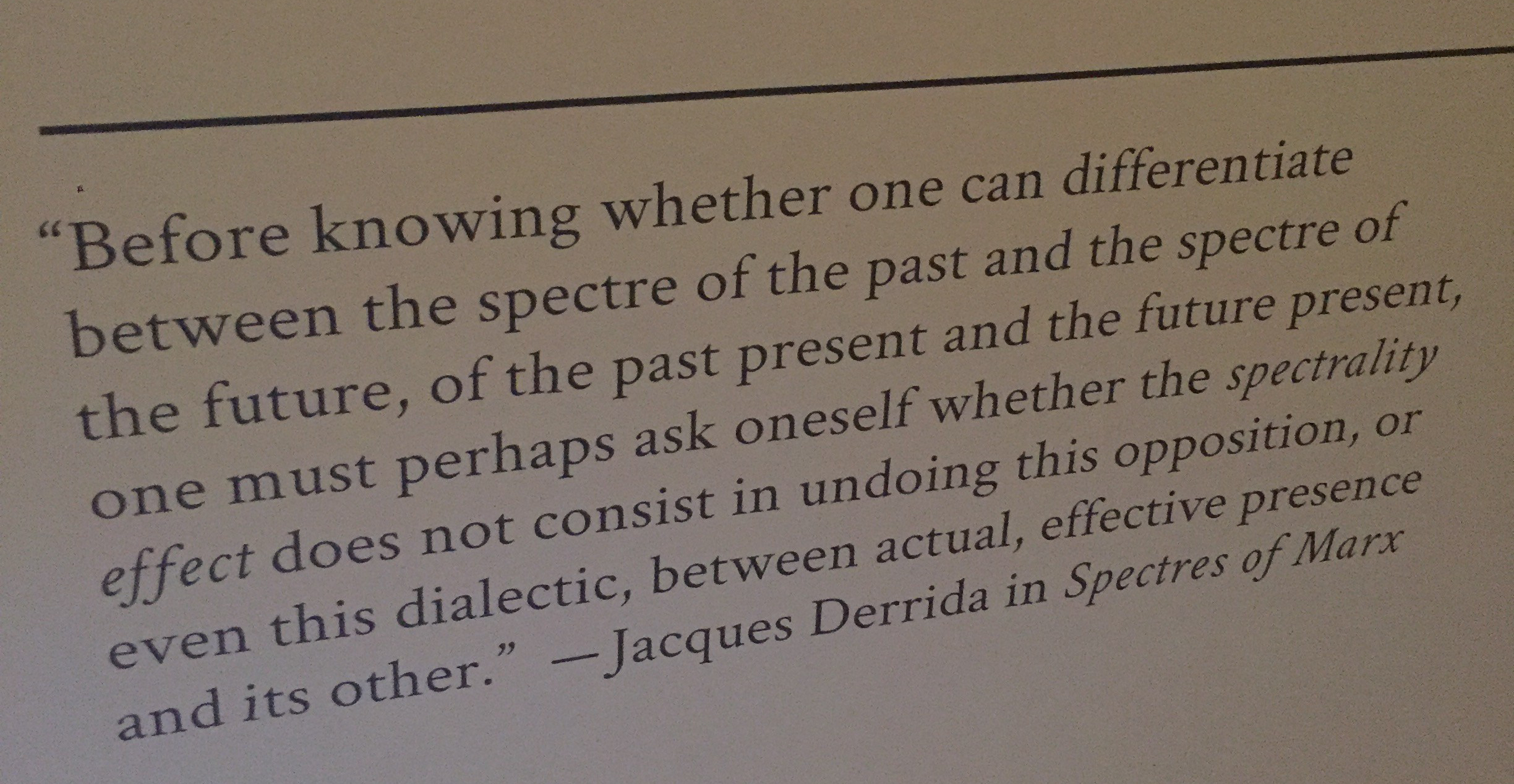

A small group goes in with me on a tour of sorts conducted by someone from the CCA, but I hang back and decide to let them have their run before going into the first installation space to avoid listening to the hurried commentary. The walls as I enter the exhibition hall are decorated with a few quotes. The first one, uncredited (so probably the words of the curators), ended powerfully and promisingly:

“Challenging one-sided narratives by exposing facts and rewriting histories is a necessary subversive act of resistance against manipulation and distortion of truth.”

There are so many buzzwords of transgression in that punchy, urgent sentence that I can’t help but raise both eyebrows and press my lips together in a mixture of skepticism and hope.

This quote was followed by a series of quotes from Freud and especially Jacques Derrida’s Spectres of Marx, the latter, with its ideas of hauntology and the ghostly presence-absence of a past that is always present and a future that will never arrive, is a particularly apt source material for the exhibition.

After fiddling with the curtain, I enter Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen’s installation, The Nameless. I cannot tell you exactly why, after sitting and watching this projection for a suitable period of time, I remain unmoved and perhaps even a little exasperated. It’s all very clever – Ho appropriates and splices ‘found footage’ from the filmography of Hong Kong actor Tony Leung Chiu Wai to tell the story of Sino-Vietnmese triple agent “Lai Teck”, the former General Secretary of the Communist Party of Malaya (1939-1947) and a man of many aliases without a name. Tony Leung, who has also adopted many names in countless films, is perfect as the persona of Lai Teck. The curatorial decision to erect a double projection of Ho’s film (one narrated in Vietnamese and one in Chinese) back-to-back in the middle of the room, separated only by a gauzy fabric, “allows viewers to see one version at a time, yet catch a glimpse of the viewers watching the other”. In the program booklet’s words, “The Nameless mirrors the content of the film by making it function and communicate like a triple agent in itself” (pg. 9).

Image from The Nameless (2015), courtesy of Galerie Michael Jannssen

Perhaps it’s the fact that the program booklet stipulates very clearly and almost smugly what The Nameless and its curatorial arrangement is meant to mean, which lies uncomfortably with the work’s claim to ambiguity, mystery and narrative indeterminacy. Perhaps it’s because I had close to no sense of ‘Southeast Asia’ from the footage with the exception of the Vietnamese narration. Ultimately, I stay impassive probably because the work strikes me as so overwhelmingly male, as I – primed with Freud and Derrida – watch (with narrowed eyes) masculine faces and bodies brooding, smoking, or writhing on screen in violent, blood-stained agony.

I find my way out to Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Fireworks (Archives), another video installation but this time displayed on a transparent screen suspended in the middle of a large open foyer of sorts. I sit down. I stand up. I walk around the screen. I am in awe, in the sublime sense of admiration tinged with fear, as I am alone with a work so understatedly confronting thanks to the effect of its staging: haunting, stroboscopic images that crackle and spit into the void of the space, casting light and shadow rapidly and randomly on the walls, on the floor and on my body.

I am not exaggerating when I say that this work effortlessly throws out the conventional dimensions of cinema and spectatorship. I am drawn harshly back into reality when, quietly, Apichatpong shows us the images of several Thai communist rebels who were killed in the 1970s. This time, instead of telling us what to think and feel, the accompanying text gives us crucial context on the setting of the film (Sala Keoku, a Buddhist-Hindu garden and hybrid entity unrecognised by the state) and Apichatpong’s approach as a filmmaker.

Keeping an eye on the word count, I will mention two other important works in this exhibition. One is not a main installation but a “research project” in “the lab” by siren eun young jung, a displayed collection of oral histories of Yeoseong Gukgeuk performers (a dying genre of musical theatre with characters exclusively played by women), and the other is a 2007 documentary LOVE MAN LOVE WOMAN by Nguyen Trinh Thi about an gay Đạo Mẫu spirit medium in Hanoi whose open effeminacy is afforded by his revered role as a performer of religious folk rituals. Both pieces of work interrogate and interrupt the spaces between body, identity and history through performance and performativity, but not in expected or straightforward ways.

While, for instance, the description of LOVE MAN LOVE WOMAN in the booklet (pg. 9) suggest that it is about gay men in a conservative Vietnamese society being empowered to have “the freedom to be accepted and celebrated as they are”, the documentary itself is more nuanced in its position on gender and societal politics. Is it really a story of empowerment and celebration? Or is it also a complex story of a complicated man (Master Luu Ngoc Duc) who boasts about his superiority over female mediums, who was sexually abused as a child by a math tutor, who believes people can contract homosexuality like a disease (but doesn’t want to be ‘cured’ himself), who worries about his image as a ‘vixen’ but openly talks about his sexuality?

I end my visit to NTU CCA with an “exhibition (de)tour” by renowned National University of Singapore Professor of Sociology Chua Beng Huat. Chua provides the historical context of communist violence in Southeast Asia and Korea in an engaging and accessible way. He also explicitly interweaves the Singaporean context into the exhibition, which, for all the program’s rhetoric on subverting grand narratives, conspicuously (and perhaps deliberately) fails to deal with The Singapore Story of its homeground in its installations. Acknowledging the fact that Singapore’s post-independence history, at the very least, does not include massacres or public executions, Chua nevertheless states, reminiscent of Paul Connerton’s work on collective amnesia, that: “Forgetting is just as important in history as remembering. […] Forgiving is also important, but to forgive someone needs to take up responsibility of wrongdoing. This is what the [People’s Action Party, Singapore’s ruling party] will not do. […] The PAP needs to keep communism alive today because that is the justification of their existence. [Anti-communism] marked their birth.”

It seems, from his talk and this exhibition, that a spectre is haunting ‘Asia’ despite ‘its’ apparent desire to forget… or more accurately and actively perhaps, to continually and performatively suppress?

The exhibition will be in the NTU CCA until 19th November 2017. Be prepared to walk uneasily and hurriedly through the Barracks if you emerge from the building at night.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss