Seventy five years ago this month, Australia, the UK, US and the Netherlands suffered a series of disastrous naval defeats against Japan in the narrow straits and seas around Indonesia. The warship wrecks in the Java Sea and the Sunda Strait are the final resting place for thousands of Allied sailors.

The sites are considered war graves by survivors and their descendants, following a long maritime tradition of respecting human remains on shipwrecks.

So it was with deep shock that an international team surveying the Java Sea wrecks in November 2016 found that at least four Dutch and British shipwrecks – and one American submarine whose entire crew was captured alive – had simply vanished from the seabed some 70 metres below. This video shows the profound disappointment of the divers when they realised the wrecks they had set out to survey were no longer there.

The ships were enormous – HMS Exeter, for example, was a 175-metre heavy cruiser, longer than three Olympic-sized swimming pools. Other Allied ships in Indonesian waters have also been damaged.

The evidence suggests that the missing ships were stolen, or salvaged, for the valuable metal now sitting on the sea floor.

History repeating

HMAS Perth, showing the ship’s distinctive, angular camouflage design (on starboard side only), 1942. Photo: Australian War Memorial.

The recent desecration of the Java Sea naval wrecks was unsurprising to those familiar with the state of underwater cultural heritage in Indonesia. Last year, Inside Indonesia reported on measures being taken to mitigate damage to two other Allied wrecks in Indonesia: HMAS Perth and USS Houston in the Sunda Strait, west of Jakarta. These naval ships were attacked by a Japanese fleet in the early hours of 1 March 1942, sinking with over a thousand lives lost between them.

In 2013, reports emerged of salvage barges removing scrap metal from the sites. Although Indonesian authorities were not identified as participating in the salvage operations, they were criticised for not doing more to protect the wrecks.

Memorial service for HMAS Perth at HMAS Kuttabul naval base (Garden Island, Sydney), February 2017. Photo: Natali Pearson

Well-meaning recreational divers have also been implicated. In 2013, a diver removed a trumpet from USS Houston, an action that was met with widespread criticism. The USS Houston Survivors’ Association, to whom the diver had attempted to gift the trumpet, rejected it on the basis that US law deemed it illegal to remove property from a US Navy wreck without authorisation. As Executive Director of the Survivors’ Association, John Schwarz, said:

We have no idea of the untold number of other divers who have pilfered our ship […] and have kept relics retrieved for their own personal use, “stealing” that which truly belong [sic] to the lasting memory of the bravery and dedication of the men who served on these warships.

The trumpet was eventually passed to the underwater archaeology branch of the US Naval History and Heritage Command, where it is now undergoing conservation.

A trumpet recovered from USS Houston in 2013 undergoes conservation. Photo: Michael Ruane / The Washington Post

Advocacy groups in Australia have long called on authorities to protect HMAS Perth. While a recent sonar scan confirmed that USS Houston was largely intact, results for HMAS Perth were inconclusive. Australian and Indonesian divers are due to return to the site in March. Despite these efforts, some feel that it is already too late to protect HMAS Perth.

HMAS Perth, as photographed by the US Navy on an inspection dive with the Indonesian Navy (TNI-AL), 2015. Photo: US Navy / Australian National Maritime Museum

Why steal a ship?

Naval shipwrecks mean huge amounts of scrap metal, with significant potential re-sale value. The sheer quantity of scrap metal on a naval ship means that a single wreck can be worth up to A$1 million. The bronze propellers alone are worth tens of thousands of dollars each.

The presence of a finite resource known as ‘low background steel’ on the Java Sea wrecks may have also been a temptation for salvagers. This refers to the level of radio-activity in steel that was manufactured prior to the ‘Trinity’ above-ground nuclear test in July 1945 and the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month. These, and the hundreds of other above-ground nuclear tests that took place in the ensuing decades, contributed to an increase in worldwide atmospheric radiation levels and attendant levels of new steel. Even though atmospheric radiation levels have decreased since the introduction of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, modern steel production is still affected by the remaining radioactive particles in the atmosphere. Modern steel, while not a health hazard, cannot be used in finely-calibrated instruments that measure radiation such as Geiger counters and certain medical and scientific equipment. It is in such applications that low background steel – that is, steel manufactured pre-1945, especially that which was underwater during the 1950s and 1960s – is particularly valuable.

It is doubtful that the salvage was conducted in complete secrecy: removing a shipwreck from the seabed requires time, know-how, and money. The Java Sea wrecks lay close to one of Indonesia’s largest naval bases, and suspicious activity – not to mention visible environmental impacts such as oil spills – is unlikely to have gone unnoticed by passing marine craft.

Poor visibility limits clear photos of HMAS Perth. Photo: Shinatria Adhityatama / Pusat Arkaeologi Nasional (Arkenas), 2014

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, other naval shipwrecks have also fallen victim to illegal salvaging. In 2014, reports emerged of the destruction of British battlecruisers HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales in Malaysian waters. In this instance, the salvage operations appear to have been relatively unsophisticated – divers operated from a small boat disguised as a fishing vessel, and placed homemade explosives, packed in coffee tins, on the wreck to break it up before the arrival of a larger salvage vessel. Dives would have been complicated by fast-moving currents and low visibility, and the use of rudimentary diving equipment such as thin rubber hoses connected to rusty air compressors.

Despite these challenging conditions, illicit salvage of warship wrecks has continued to occur in Southeast Asia – and appear to have become increasingly sophisticated.

In January 2017, fresh reports emerged of World War II wrecks being salvaged. This time, the vessels were Japanese cargo ships, and were located off the coast of Borneo in Malaysian waters. Known collectively as the Usukan wrecks, they supported a spectacular marine eco-system and were popular dive sites. However, a Chinese-registered vessel, complete with a giant crane for hoisting underwater objects, was sighted removing material from the wrecks. Disturbingly, the salvors claimed they had been authorised by the archaeology department at Universiti Malaysia Sabah, and that their operations were for research purposes. Community outrage resulted in permission to operate being withdrawn, but the damage had been done: investigators later found an anchor from one of the Japanese wrecks stowed on board the salvage vessel. While their historical significance is undisputed, the destruction of these wrecks has also resulted in the loss of livelihoods for local fishermen and tourist dive operators.

A China-registered vessel is spotted by divers above a site where three Japanese second world war ships lie off the coast of Borneo. The wrecks have been destroyed by a metal salvage operation. Photo: The Guardian

My conversations with people close to the issue suggest that the Java Sea wrecks were removed using a major surface platform known as a claw barge. This reduces the need to rely on large numbers of divers, and, if operated together with specialist imaging equipment such as a sonar scanner, would maximise the efficiency of the salvage. It is also believed that the crew were armed. They gave little-to-no consideration to objects of historical or archaeological significance.

Silent witnesses

Nor does the presence of human remains on these wrecks deter illicit salvagers from their nefarious activities. The removal of propellers and trumpets is one thing, but the desecration of submerged war graves is undoubtedly the most troubling aspect of this story.

However, the legal status of underwater war graves is ambiguous. Although (or because) many of the larger maritime powers hold strong views on the issue, there is no international consensus on the issue of war graves on sunken warships.

Some commentators, concerned about the protection of the World War II wrecks, have urged Southeast Asian countries to sign the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the protection of the underwater cultural heritage. At present, the only Southeast Asian signatory is Cambodia (the Dutch, UK, US and Australia are not yet party to this Convention either).

However, the relevance of the Convention is limited, as it relates to underwater war graves, by the simple fact of the wrecks’ age: the Convention defines heritage as that which has been underwater for at least 100 years, thus excluding World War II wrecks. Even if these wrecks were older than 100 years, the Convention’s treatment of those who have perished at sea is focused on human remains generally, not military human remains specifically.

Furthermore, the question of what constitutes ‘proper respect’ is not defined, and is thus open to interpretation across countries and cultures.

Some observers have examined Indonesia’s obligations relating to commercial seabed exploitation under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This Convention, to which Indonesia is a party, imposes a general duty to protect ‘archaeological and historical objects found at sea’, a description that would not be hard to justify in relation to the Java Sea or Sunda Strait wrecks. Theoretically, however, this could be contested, as ‘archaeological and historical’ remains undefined. And whether or not UNCLOS has a framework to apply protective measures is, again, another matter.

In the absence of effective bilateral or multilateral agreements, the onus falls on states to make appropriate provisions for war grave recognition in their domestic legislation. Under Indonesian Law No: 11 of 2010 concerning Cultural Conservation, objects older than 50 years can be considered as cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, none of the wrecks mentioned in this article have been afforded official recognition under this legislation – in fact, not a single underwater site has been heritage listed. Without the protection that an official heritage listing would provide, Indonesian authorities are not able to prosecute illicit salvagers or looters.

Shifting responsibility

The international community has condemned the disappearance of the Java Sea wrecks, with the Dutch launching an immediate investigation. The UK Ministry of Defence also expressed serious concern about “unauthorised disturbance of any wreck containing human remains”, and requested that Indonesian authorities take “appropriate action”.

When the news broke that the ships had vanished, the head of Pusat Penelitian Arkeologi Nasional (National Archaeological Centre of Indonesia), Bambang Budi Utomo, was quoted as saying:

The Dutch government cannot blame the Indonesian government because they never asked us to protect those ships. As there was no agreement or announcement, when the ships go missing, it is not our responsibility.

Chief of Indonesia’s Navy Information Office, Colonel Gig Jonias Mozes Sipasulta, confirmed Indonesia’s view that the Dutch, British and US governments should have done more to protect the wrecks:

The Indonesian navy cannot monitor all areas all the time. If they ask why the ships are missing, I’m going to ask them back, why didn’t they guard the ships?

Although Indonesia quickly committed to investigating the mystery of the missing wrecks, these initial messages undoubtedly caused further damage to Indonesia’s already-troubled reputation when it comes to conserving underwater heritage.

This perception is partly due to Indonesia’s history of permitting the commercial excavation of historic shipwrecks.

Under this system, licences were sold to commercial operators to excavate shipwrecks, and the salvaged objects were sold for profit. To my knowledge, this policy was never extended to modern warships. Although there is now a moratorium on commercial excavation in Indonesia, it has unquestionably contributed to an environment in which shipwrecks are valued at least as much – if not more – for their economic potential as their historical or archaeological significance.

Reducing vulnerabilities

Despite these mis-steps, there are many professionals in Indonesia who are keenly aware of the responsibilities and sensitivities associated with managing and protecting underwater cultural heritage, particularly high-profile naval vessels.

At the Research Institute for Coastal Resources and Vulnerability, housed within Indonesia’s Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, researchers such as Nia Naelul Hasanah Ridwan have been working on the HMAS Perth site since 2015. This multi-disciplinary project brings together maritime archaeologists and policy makers from the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, as well as representatives from the Ministry of Education and Culture.

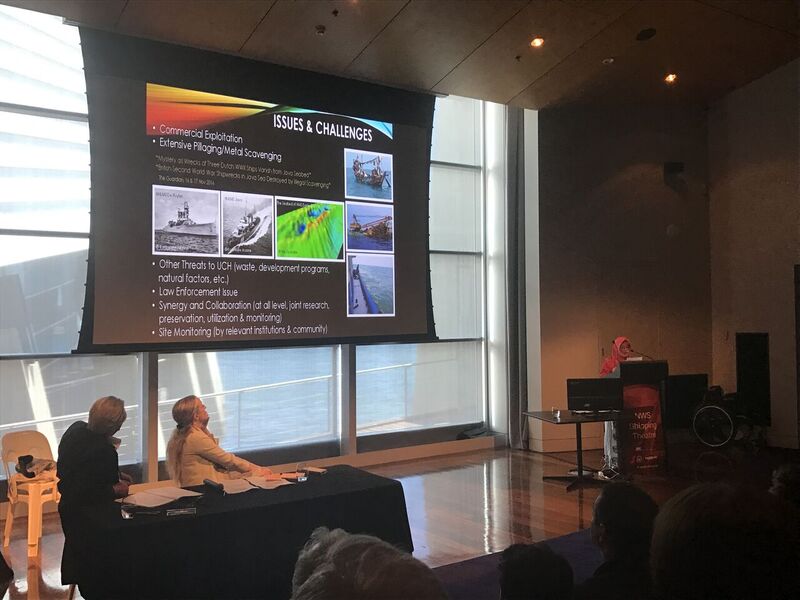

Nia Naelul Hasanah Ridwan presenting at a UNESCO Roundtable on underwater cultural heritage, at the WA Maritime Museum, Fremantle. 2016. Photo: N. Pearson

The research team has used a range of methods to determine HMAS Perth’s condition and assess its vulnerability to a range of threats. These methods include site recording, water quality and side scan sonar measurements, and analysis of waste pollution through the simulation of hydrodynamics and trajectories of debris particles.

The results confirm that the wreck has been damaged by salvagers. There are other threats too, including overly-enthusiastic recreational divers, sea sand mining operations, shipping traffic, and marine pollution from coastal development in nearby Banten Bay.

At the IKUWA international maritime archaeology conference in Fremantle last year, Ridwan confirmed that the HMAS Perth site’s significance and vulnerability warrants ongoing attention from Indonesian authorities. To this end, the project team is considering the introduction of a maritime conservation area around the HMAS Perth site, similar to that in Natuna. Last year, Nia and her team also conducted awareness raising sessions with local communities and authorities, something she believes is key to reducing damage to the site.

Other suggestions include the use of public display signs, and expanding commemoration activities to include coastal communities.

Nia Naelul Hasanah Ridwan from the Research Institute for Coastal Resources and Vulnerability, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, at an international maritime archaeology conference in Fremantle, 2016. Photo: Natali Pearson

Ridwan’s presentation included photos of photos of metal scavenging operations in Indonesia. 2016. Photo: Natali Pearson

There are also efforts being made to increase awareness within the broader population. In Jakarta, the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries’ new Marine Heritage Gallery will bring underwater objects to both government officials and the general public. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Education and Culture is developing an online museum dedicated to promoting knowledge and understanding of Indonesia’s underwater cultural heritage.

The new Marine Heritage Gallery (located at Mina Bahari Building 4, 2nd floor, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Jalan Batu, Gambir, Jakarta Pusat) displays approximately 1000 objects from three historically significant shipwrecks: the Belitung, Pulau Buaya and Cirebon. 2017. Photo: Ministry Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Indonesia

In Sulawesi, one of Indonesia’s busiest maritime trading destinations, there are plans to open a Regional Training Centre for Underwater Cultural Heritage inside Makassar’s historic Fort Rotterdam.

As recent research on HMAS Perth demonstrates, warship wrecks – and shipwrecks more generally – are vulnerable to a range of threats.

But these threats are not unique to Indonesia.

Britain has also been in the news recently for not protecting its warships in the North Sea, where unauthorised salvagers are alleged to have disturbed at least half of the wrecks from the 1916 Battle of Jutland. With over 8000 lives lost, the destruction has been likened to stealing headstones from a military cemetery.

Sunken warships have both historical and emotional significance. They must be valued for more than their scrap metal re-sale value. Given the ambiguities and complexities of protecting these important naval sites, it is imperative that Flag and Coastal States work together rather than trading diplomatic blows.

This year, the 75th anniversary of their sinking, is the ideal time to actively promote a greater awareness of these warship wrecks, and to work towards a more collaborative model that builds on existing bilateral and multilateral relationships.

Opportunities exist for Flag and Coastal States to share information, conduct capacity-building and training exercises together, and develop mutually beneficial solutions to the challenge of protecting these warships. This model could build on the cooperation already being displayed by Indonesian and Australian cultural institutions to include, for example, technical assistance and legal advice, and could be further extended to include community-focused activities at the local level. Indonesia has already indicated its support for joint site monitoring.

The responsibility to protect and preserve underwater cultural heritage extends to all states, not just those that have lost wrecks or have wrecks in their waters. Internationally, the United Nations’ Ocean Conference will convene in New York in June with the aim of reversing the decline in the health of the world’s oceans. So far underwater cultural heritage is not on the agenda. It is up to UN members to ensure that these issues, and not just marine life, get their time in the spotlight.

***

A documentary about the missing Java Sea wrecks screened on Dutch TV channel NPO2 on Sunday 26 February – you can see a trailer here.

This article was first published in The Conversation and republished on the ABC.

Facebook

Facebook  Twitter

Twitter  Soundcloud

Soundcloud  Youtube

Youtube  Rss

Rss